Build Audit Systems That Reveal Truth and Improve Performance

Disclaimer.

This article provides general guidance, frameworks, and examples to support the development of maintenance audit programs.

It is intended for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute legal, regulatory, safety, or compliance advice.

Every organization operates within its own technical, operational, and regulatory environment. The concepts and examples presented here should be adapted to your specific context, risk profile, and jurisdictional requirements. They are illustrative only and not prescriptive standards.

Organizations remain solely responsible for their own decisions, risk assessments, and compliance obligations.

Where appropriate, consult qualified professionals or auditors with experience in your industry before implementing or modifying audit processes.

Any views or interpretations expressed are those of the author and do not represent the positions of any employer, client, government body, or vendor referenced in this article.

Article Summary.

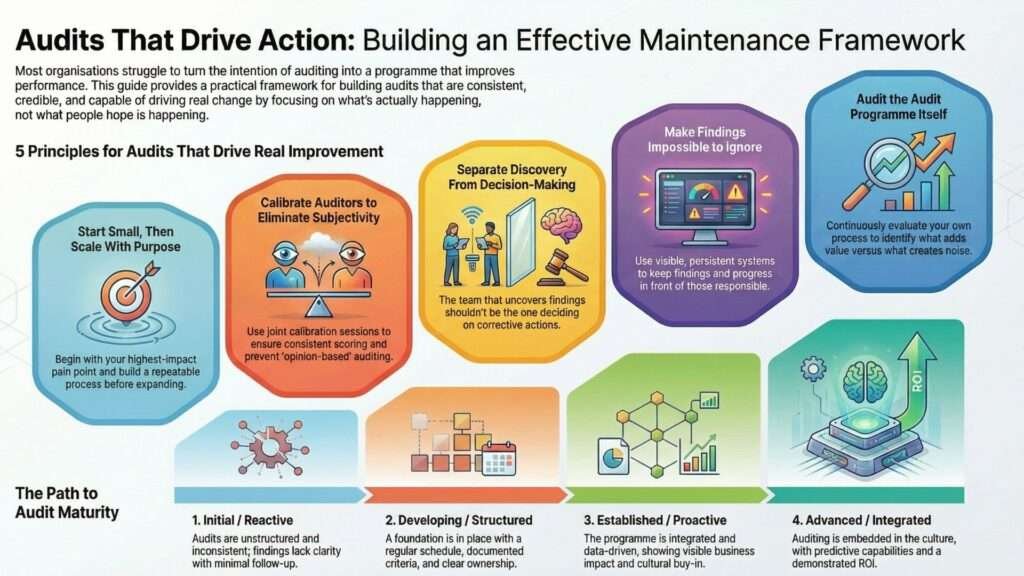

Most organizations know they need audits, what they struggle with is turning that intention into a program that actually improves performance.

This article closes that gap. It breaks down the practical mechanics of building a maintenance audit framework that is consistent, credible, and capable of driving real operational change.

Instead of abstract principles, you’ll find concrete methods for structuring audit teams, designing scoring systems that eliminate subjectivity, creating audit calendars that don’t disrupt operations, and training auditors who know how to uncover truth rather than confirm assumptions. The focus is simple: audits that reveal what’s really happening, not what people hope is happening.

Drawing on implementation experience across multiple industries, this article tackles the realities most audit frameworks ignore, limited resources, skeptical stakeholders, inconsistent documentation and the challenge of maintaining objectivity when auditing your own colleagues.

You’ll get practical solutions, ready‑to‑use templates, and a roadmap for turning audit findings into actions that stick.

If you want an audit program that does more than generate reports, this is where you start.

Top 5 Takeaways.

1. Start Small, Then Scale With Purpose: Trying to audit everything at once spreads resources thin and produces shallow results. Begin with your highest‑impact pain point, build a repeatable process, and expand only when the foundation is solid.

2. Calibrate Auditors to Eliminate Subjectivity: Five auditors should not produce five different scores. Joint calibration sessions create consistency, strengthen confidence in results, and prevent “opinion‑based” auditing.

3. Separate Discovery From Decision‑Making: The people who uncover findings shouldn’t be the ones deciding corrective actions. This separation reduces defensiveness, increases honesty, and leads to more actionable outcomes.

4. Make Findings Impossible to Ignore: Audit reports hidden in shared drives don’t change behaviour. Use visible, persistent systems that keep findings, actions, and progress in front of the people responsible for fixing them.

5. Audit the Audit Program Itself: High‑maturity organizations continuously evaluate their own audit process. Identify what adds value, what creates noise, and where auditors spend time without improving performance.

Table of Contents.

1.0 Designing Your Audit Program Architecture.

1.1 Deciding What to Audit First.

1.2 Setting Audit Frequency and Depth.

1.3 Resource Planning for Audit Activities.

1.4 Creating Your Audit Calendar.

1.5 Balancing Breadth Versus Depth.

2.0 Building Effective Audit Criteria and Scoring Systems.

2.1 Moving Beyond Subjective Assessments.

2.2 Developing Observable Evidence Requirements.

2.3 Creating Meaningful Scoring Rubrics.

2.4 Weighting Criteria by Impact.

2.5 Testing Your Criteria Before Rollout.

3.0 Assembling and Training Your Audit Team.

3.1 Selecting Auditors with the Right Mindset.

3.2 Internal Versus External Auditors.

3.3 Cross-Functional Audit Benefits.

3.4 Auditor Training Programs That Work.

3.5 Maintaining Auditor Objectivity and Independence.

4.0 Conducting the Physical Audit.

4.1 Pre-Audit Preparation and Communication.

4.2 Opening Meetings That Set the Right Tone.

4.3 Evidence Gathering Techniques.

4.4 Real-Time Documentation Methods.

4.5 Managing Difficult Conversations During Audits.

5.0 Mastering the Art of Audit Questioning.

5.1 Why Most Auditors Ask Terrible Questions.

5.2 The STAR Technique for Behavioral Auditing.

5.3 Following the Evidence Trail.

5.4 Detecting Social Desirability Bias.

5.5 When to Push and When to Pivot.

6.0 Documenting Findings That Drive Action.

6.1 Writing Findings That Can’t Be Ignored.

6.2 Classifying Finding Severity Appropriately.

6.3 Linking Findings to Business Impact.

6.4 Photographic Evidence and Work Samples.

6.5 Creating Finding Statements That Survive Challenges.

7.0 Turning Audit Results Into Improvement Plans.

7.1 Prioritization Frameworks for Findings.

7.2 Assigning Ownership and Accountability.

7.3 Developing Realistic Timelines.

7.4 Resource Allocation for Corrective Actions.

7.5 Creating Feedback Loops That Close the Gap.

8.0 Tracking and Reporting Audit Outcomes.

8.1 Dashboard Design for Audit Programs.

8.2 Trend Analysis Across Multiple Audits.

8.3 Executive Reporting That Drives Decisions.

8.4 Celebrating Improvements and Recognizing Progress.

8.5 Using Data to Refine Future Audits.

9.0 Overcoming Common Audit Program Challenges.

9.1 Dealing with Audit Fatigue.

9.2 Managing Defensive Responses.

9.3 Preventing Audit Preparation Theater.

9.4 Maintaining Momentum Between Audit Cycles.

9.5 Avoiding the Compliance Checkbox Trap.

10.0 Specialized Audit Approaches for Complex Scenarios.

10.1 Auditing Newly Implemented CMMS Systems.

10.2 Post-Incident Root Cause Audits.

10.3 Vendor and Contractor Maintenance Audits.

10.4 Pre-Acquisition Due Diligence Audits.

10.5 Benchmarking Audits Against Industry Standards.

11.0 Technology Tools for Modern Maintenance Auditing.

11.1 Digital Audit Platforms and Mobile Apps.

11.2 Automated Data Collection from CMMS.

11.3 AI-Assisted Anomaly Detection.

11.4 Photograph and Video Documentation Systems.

11.5 Collaborative Audit Workflow Software.

12.0 Building a Culture That Welcomes Audits.

12.1 Shifting from Blame to Learning.

12.2 Transparent Communication About Audit Purpose.

12.3 Involving Front-Line Staff in Audit Design.

12.4 Sharing Audit Insights Across Departments.

12.5 Recognizing Teams That Embrace Audits.

13.0 Conclusion.

14.0 Bibliography.

1.0 Designing Your Audit Program Architecture.

Before you audit anything, you need a plan. Not a vague intention to “check things more often,” but an actual architecture that defines scope, frequency, resources and success criteria. Most organizations skip this step and wonder why their audit efforts feel chaotic and deliver inconsistent value.

1.1 Deciding What to Audit First.

You can’t audit everything simultaneously and you shouldn’t try. The organization that attempts comprehensive audits across all maintenance modules in month one typically produces shallow assessments that miss critical issues while consuming enormous resources.

1.1.1 Start with your biggest pain point.

If your backlog is getting far too big, audit your work planning and scheduling processes first.

If you’re experiencing repeat failures on critical equipment, focus on your preventive maintenance strategy and execution. If work orders sit incomplete for months, examine your work identification and completion processes.

Here’s a practical prioritization approach: gather your leadership team and list your maintenance challenges.

For each challenge, rate it on two dimensions, business impact (how much does this hurt us?) and audit feasibility (how easily can we assess this?).

Plot these on a simple matrix. Your first audit target sits in the high-impact, high-feasibility quadrant.

1.1.2 Consider your CMMS implementation status.

Organizations with recently implemented systems should audit master data quality and user adoption before diving into complex process audits.

You can’t meaningfully assess work planning quality if your equipment register contains duplicate assets and your parts catalog is chaos. Fix the foundation first.

1.1.3 Think about political realities.

Some areas are politically sensitive, tightly controlled by powerful managers or historically resistant to external scrutiny.

While these might need auditing eventually, starting there can doom your entire program. Build credibility by delivering value in more receptive areas first.

Success creates momentum and political capital for tackling harder challenges later.

1.2 Setting Audit Frequency and Depth.

How often should you audit each module? The frustrating answer: it depends. However, some principles can guide your decisions.

1) High-risk, high-variability processes need more frequent audits: If you operate in industries with stringent safety requirements, audit your isolation procedures, pre-job briefings and hazard identification processes quarterly. These aren’t “check the box” exercises, they’re proactive defenses against incidents that could injure people or shut down operations.

2) Stable, well-controlled processes can be audited less frequently: If your master data management has been solid for three years running, an annual audit might suffice. Redirect those audit resources toward areas showing more volatility.

3) Distinguish between comprehensive and surveillance audits: Comprehensive audits examine every aspect of a module in detail. These might occur annually or biennially. Surveillance audits target specific high-risk elements or recently identified problem areas. These lighter-touch assessments can happen monthly or quarterly, keeping attention focused without overwhelming resources.

4) Consider your improvement velocity: Organizations implementing major changes should audit affected processes more frequently to verify improvements are taking hold. Once changes stabilize and become routine, you can reduce frequency. Audit frequency should flex based on need, not follow a rigid calendar.

1.3 Resource Planning for Audit Activities.

Audits consume time and time is your scarcest resource. Realistic resource planning prevents audit programs from collapsing under their own ambition.

1.3.1 Calculate the actual hours required.

A comprehensive module audit isn’t a two-hour walkthrough.

Planning, preparation, interviews, observations, documentation review, analysis, report writing and follow-up meetings easily consume 40-80 hours depending on facility size and complexity.

Multiply that by your intended frequency and number of modules.

Does that total fit within available resources? If not, either reduce scope or secure additional resources.

1.3.2 Don’t rely solely on maintenance managers for auditing.

They’re already stretched thin managing daily operations. Expecting them to conduct thorough audits in their “spare time” guarantees superficial results.

Consider dedicating reliability engineers, creating rotating audit teams, engaging external consultants for specialized assessments or training coordinators specifically for audit activities.

1.3.3 Account for auditee time too.

The people being audited need time to participate in interviews, locate documentation, explain processes and respond to findings.

An audit that shows up unannounced demanding immediate attention creates resentment and disrupts operations.

Schedule audits during periods of lower operational intensity when possible and communicate time requirements upfront.

1.3.4 Build buffer capacity.

Audits uncover issues requiring immediate attention.

If you schedule every available hour for planned activities, unexpected findings derail everything downstream.

Maintain at least 20% buffer capacity in your audit resource planning for investigation and urgent responses.

1.4 Creating Your Audit Calendar.

A well-structured audit calendar provides predictability, ensures coverage and prevents conflicts. It’s the difference between strategic assessment and random inspection.

1.4.1 Map out your full year.

Start with a blank annual calendar and block out periods when audits would be disruptive or impractical, major shutdowns, peak production periods, holiday weeks. These blackout periods protect operations and respect the reality that timing matters.

1.4.2 Distribute audits evenly.

Conducting all audits in Q4 creates a crushing workload and positions findings as “year-end problems” rather than continuous feedback.

Spread audits throughout the year, creating steady rhythm rather than frantic bursts.

1.4.3 Coordinate with other assessment activities.

Your organization likely conducts safety audits, quality audits, environmental audits and financial audits.

Coordinate timing to avoid audit fatigue, where teams face back-to-back assessments with no breathing room.

Consider combining related audits where appropriate, safety and work readiness audits often examine overlapping topics.

1.4.4 Communicate the calendar widely.

Publish your audit schedule at least 60 days in advance. This transparency allows teams to prepare properly, schedule key personnel to be available and eliminate the “surprise audit” dynamic that breeds defensiveness.

Some organizations resist this transparency, fearing people will “put on a show” for audits. That’s actually a good sign, if people feel compelled to improve things before audits, your program is already creating value.

1.5 Balancing Breadth Versus Depth.

Every audit involves tradeoffs between breadth (how much ground you cover) and depth (how thoroughly you examine each topic). Finding the right balance determines whether you spot systemic issues or just skim the surface.

1.5.1 Shallow audits across many topics reveal patterns.

If you’re trying to establish baseline performance across all modules, broader coverage makes sense.

You’re looking for “red flag” areas that warrant deeper investigation, not conducting forensic analysis of each process. This approach works well in early audit program stages when you’re still mapping the landscape.

1.5.2 Deep dives reveal root causes.

Once you’ve identified problem areas, subsequent audits should go deeper. Interview more people at different levels.

Examine multiple work orders rather than representative samples. Shadow technicians during actual work execution.

Follow processes end-to-end rather than checking discrete elements. This depth uncovers why problems persist despite previous “fixes.”

1.5.3 Consider rotating focus.

Some organizations conduct broad annual audits supplemented by quarterly deep dives into specific modules.

Q1 might examine work planning in detail while touching other modules lightly.

Q2 deep dives into CMMS data quality.

Q3 focuses on maintenance strategy.

This rotation ensures everything gets examined while maintaining manageability.

1.5.4 Let findings drive depth decisions.

If a broad audit reveals excellent performance in an area, you don’t need to dig deeper, acknowledge success and move on.

Conversely, superficial findings that hint at deeper issues warrant immediate follow-up investigation.

Audit depth should follow evidence, not predetermined plans.

2.0 Building Effective Audit Criteria and Scoring Systems.

Audit criteria answer the fundamental question: “What does good look like?”

Without clear, observable criteria, audits devolve into opinion contests where different auditors reach wildly different conclusions about the same evidence.

Effective criteria transform subjective assessment into objective measurement.

2.1 Moving Beyond Subjective Assessments.

“How good is your work planning?” This question invites subjective responses and produces unreliable data.

One auditor might think planning is excellent because written procedures exist.

Another might rate it poor because actual practice diverges from procedures. Both are looking at the same reality but applying different standards.

2.1.1 Define specific, observable behaviors and artifacts.

Instead of asking “Is work planning effective?” ask “What percentage of planned work orders include complete parts lists verified against inventory before scheduling?” This specificity transforms a fuzzy concept into something measurable.

2.1.2 Create clear performance levels.

Rather than “good/bad” or “satisfactory/unsatisfactory,” define what performance looks like at different levels. For work order planning, you might specify:

1) Advanced (90-100%): All planned work orders contain detailed task lists, accurate time estimates validated against historical data, complete parts lists cross-referenced with inventory, safety requirements identified, required permits specified and quality standards defined. Work packs include relevant drawings, procedures and reference materials.

2) Proficient (70-89%): Planned work orders consistently include task lists, time estimates and parts lists. Most reference required permits and safety measures. Work packs contain basic documentation though some materials may be missing. Estimates generally align with historical performance.

3) Developing (50-69%): Work orders have basic task descriptions and parts lists, but time estimates are often inaccurate. Safety requirements and permits are sometimes overlooked. Work pack documentation is incomplete. Significant variance between planned and actual execution.

4) Beginning (Below 50%): Work orders lack detailed task breakdowns. Parts lists are incomplete or missing. Time estimates are guesses. Safety requirements not systematically identified. Minimal documentation provided to technicians.

This specificity allows different auditors to assess the same evidence and reach consistent conclusions.

You’re no longer debating opinions; you’re comparing observations against defined standards.

2.2 Developing Observable Evidence Requirements.

Audit criteria should specify what evidence auditors need to collect and evaluate.

This requirement prevents audits from relying on anecdotal impressions or selective examples that don’t represent typical performance.

2.2.1 Quantitative evidence provides objectivity.

For assessing preventive maintenance compliance, don’t just ask “Are PMs being completed?” Specify: “Review the past 90 days of scheduled PMs.

Calculate the percentage completed within the specified time window.

Sample 20 completed PM work orders and verify actual tasks performed match the PM task list.”

2.2.2 Qualitative evidence adds context.

Numbers tell you what’s happening; conversations reveal why. For that same PM assessment, interview technicians about barriers to PM completion.

Observe technicians performing PMs to verify written procedures match actual practice. Ask supervisors how they prioritize work when PMs conflict with urgent corrective work.

2.2.3 Multiple evidence types triangulate truth.

The most reliable audit findings rest on evidence from multiple sources:

1) Documentation: What do procedures, work orders, inspection records and system reports say?

2) Interviews: What do people at different levels tell you about how things actually work?

3) Observations: What do you see when you watch processes in action?

4) System data: What do trends in your CMMS reveal about performance over time?

When all four evidence types align, you’re likely seeing reality.

When they contradict each other, procedures say one thing, people say another, observations show a third reality, you’ve found an important gap to explore.

2.2.4 Specify sample sizes appropriate to confidence needs.

Reviewing three work orders doesn’t provide reliable insight into overall planning quality. Statistical validity requires adequate sample sizes.

For most maintenance audits, examining 20-30 examples of a given work type provides reasonable confidence. Critical processes or those with high variability might warrant larger samples.

2.3 Creating Meaningful Scoring Rubrics.

Scoring rubrics translate audit evidence into ratings that allow comparison across time and between different areas. However, poorly designed rubrics create false precision or obscure important nuances.

2.3.1 Choose scale granularity carefully.

A three-point scale (below expectations, meets expectations, exceeds expectations) provides enough differentiation for many purposes without overwhelming auditors with hairsplitting distinctions.

Five-point scales work when you need finer gradations. Scales with more than seven points typically produce unreliable results because auditors can’t consistently distinguish between adjacent levels.

2.3.2 Consider numerical versus categorical scales.

Percentage-based scales (0-100%) feel precise but often mask subjective judgments, the difference between 73% and 78% rarely reflects measurable distinction. Pass/fail scales simplify but lose nuance.

Many organizations use hybrid approaches: numerical scores for criteria with clear quantitative evidence, categorical ratings for qualitative assessments.

2.3.3 Weight criteria by importance.

Not all audit criteria matter equally. Incomplete parts lists on planned work orders directly impact wrench time and schedule adherence, major operational impacts. Missing revision dates on procedures is a documentation gap with minimal operational impact.

Your scoring system should reflect these differences.

One approach: assign weight factors to each criterion based on its connection to safety, equipment reliability and cost.

1) Safety-critical criteria might carry 3x weight.

2) Reliability-critical criteria 2x weight.

3) Nice-to-have best practices 1x weight.

Multiply individual scores by their weight factors before calculating overall module scores.

2.3.4 Provide scoring guidance and examples.

Create a reference document that shows example scenarios for each score level.

“A score of 1 (partial) for PM task completion means technicians complete most tasks but consistently skip time-consuming activities like vibration readings or oil sampling.” These examples calibrate auditor judgment and reduce scoring variability.

2.4 Weighting Criteria by Impact.

Some audit findings matter more than others. Your scoring system should reflect this reality rather than treating all criteria equally.

2.4.1 Start with consequence analysis.

For each audit criterion, ask: “If this were deficient, what would likely happen?”

Consequences might include safety incidents, equipment failures, regulatory violations, cost overruns or missed production targets.

Severity and probability of these consequences should influence criterion weight.

2.4.2 Consider strategic importance.

Your organization’s strategic priorities should influence audit weighting.

If asset life extension is a strategic priority, criteria related to condition monitoring and predictive maintenance deserve higher weighting.

If reducing emergency maintenance costs is the top priority, criteria assessing work identification quality and planning effectiveness merit emphasis.

2.4.3 Balance technical and process factors.

Technical excellence means little if processes prevent that excellence from being applied consistently.

Weight both technical capability criteria (do people have the skills, tools and information they need?) and process execution criteria (do established processes actually get followed?).

High technical capability with poor process execution signals different improvement needs than good processes hampered by capability gaps.

2.4.4 Document your weighting rationale.

When stakeholders challenge audit scores and they will, you need clear justification for why certain criteria carried more weight.

“We weighted isolation procedure compliance heavily because our incident history shows three serious events in the past 18 months related to inadequate isolation” is defensible.

“We weighted it that way because it seemed important” isn’t.

2.5 Testing Your Criteria Before Rollout.

Never launch audit criteria organization-wide without pilot testing.

What seems clear and measurable in conference room discussions often proves ambiguous when auditors encounter real-world complexity.

1) Conduct trial audits with multiple auditors:

a. Select a representative process or area.

b. Have three different auditors independently assess it using your draft criteria. Compare their findings and scores.

c. If they reach substantially different conclusions, your criteria need clarification.

2) Identify ambiguous language:

a. Words like “appropriate,” “adequate,” “sufficient” and “reasonable” invite subjective interpretation.

b. During pilot testing, note where auditors hesitate or debate interpretation.

c. Revise criteria to eliminate ambiguity.

d. Replace “adequate parts inventory” with “critical spare parts as defined in BOMs are in stock with lead times not exceeding 72 hours for order-on-demand items.”

3) Check criterion achievability:

a. Sometimes criteria reflect ideal states that few organizations actually achieve.

b. If pilot testing reveals that even high-performing organizations score poorly, either your criteria are unrealistic or you’ve identified a universal industry weakness.

c. Distinguish between aspirational targets (useful for long-term improvement direction) and practical assessment criteria (must reflect achievable performance levels).

4) Refine evidence requirements:

a. Pilot auditors will quickly discover if evidence requirements are too burdensome, too vague or require data not readily available.

b. “Verify that all equipment has criticality rankings” is straightforward.

c. “Verify that criticality rankings were derived from formal risk assessments within the past two years” requires access to assessment documentation that may not exist or be easily located.

d. Adjust requirements to balance thoroughness with practicality.

5) Iterate based on feedback:

a. After pilot testing, gather auditors and discuss what worked and what didn’t. Which criteria produced consistent, useful findings?

b. Which generated debate without adding value?

c. What evidence proved difficult to collect?

d. Use this feedback to refine criteria before full rollout.

3.0 Assembling and Training Your Audit Team.

Audit quality depends heavily on auditor quality. The most sophisticated audit criteria and elegant scoring rubrics can’t overcome poor auditor judgment, inadequate training or wrong mindset.

Building an effective audit team requires careful selection, comprehensive training and ongoing calibration.

3.1 Selecting Auditors with the Right Mindset.

Technical knowledge matters for auditing, but mindset matters more. An auditor with average technical skills but excellent interpersonal abilities and genuine curiosity will outperform a technical expert who views auditing as fault-finding.

3.1.1 Look for people who ask “why” naturally.

Good auditors possess innate curiosity about how things work and why things happen. They’re not satisfied with surface explanations.

When someone says “that’s just how we do it,” skilled auditors probe for the underlying rationale. This curiosity isn’t aggressive, it’s genuine interest in understanding root causes.

3.1.2 Avoid auditors who need to prove they’re the smartest person in the room.

Auditing isn’t a demonstration of superior knowledge.

Auditors who can’t resist showing off their expertise or correcting minor errors create defensive environments where people hide problems rather than revealing them. The goal is discovering truth, not establishing hierarchy.

3.1.3 Seek objectivity over advocacy.

Some people excel at identifying problems but struggle to separate observation from opinion.

They see a gap between current and ideal states, assume incompetence or laziness caused it and communicate their findings with judgment rather than neutrality.

This approach destroys audit effectiveness. You need auditors who can describe what they observe without layering interpretation onto it.

3.1.4 Value emotional intelligence highly.

Auditing involves navigating sensitive conversations, managing defensive responses and building trust with people who may view audits as threatening.

Auditors need to read social cues, adjust their approach when tension rises and maintain composure when confronted with hostility.

Technical brilliance without emotional intelligence produces useless audits.

3.1.5 Consider diverse perspectives.

Audit teams composed entirely of maintenance managers think like maintenance managers. Including planners, technicians, engineers and operations personnel brings varied viewpoints that spot different issues.

Cross-functional teams also build broader organizational support for audit findings, it’s harder to dismiss recommendations when they come from peers across multiple departments.

3.2 Internal Versus External Auditors.

Should you use internal staff, external consultants or a combination? Each approach offers distinct advantages and limitations.

3.2.1 Internal auditors understand context.

They know your equipment, your history, your people and your constraints. They spot deviations from normal patterns quickly because they know what normal looks like. They’re available continuously for follow-up questions and ongoing monitoring. Internal auditors also cost less than external consultants and build organizational capability that remains after the audit concludes.

However, internal auditors face familiarity blind spots. They’ve become accustomed to workarounds and compromises that outsiders would immediately flag as problems. They may hesitate to report findings that implicate colleagues or superiors. Their availability for auditing competes with operational responsibilities, often losing priority battles when urgent issues arise.

3.2.2 External auditors bring fresh perspectives.

They haven’t become desensitized to your normal. They readily challenge “that’s how we’ve always done it” thinking because they’ve seen how other organizations handle similar situations.

External auditors typically provide more critical assessments because they have no internal relationships to protect and face no career consequences from delivering uncomfortable truths.

The downsides? External auditors require time to understand your specific context, potentially misinterpreting practices that make sense given your unique circumstances. They’re expensive.

Their involvement is episodic rather than continuous, limiting relationship building and follow-through capability.

Some organizations struggle to act on external audit findings because internal staff weren’t invested in the audit process.

3.2.3 Hybrid approaches balance strengths.

Many organizations use internal auditors for routine surveillance audits while engaging external auditors for comprehensive biennial assessments or specialized deep dives.

External auditors can also train and calibrate internal audit teams, improving their effectiveness between external visits.

This combination provides continuous internal monitoring supplemented by periodic external validation and expertise injection.

3.3 Cross-Functional Audit Benefits.

Maintenance system audits should include voices beyond maintenance leadership. Cross-functional audit teams produce more comprehensive assessments and build broader organizational buy-in.

3.3.1 Operations personnel understand how maintenance activities impact production.

They can assess whether maintenance communication is effective, whether planned outages align with operational needs and whether equipment handover processes work smoothly. Operations input prevents maintenance-centric audit myopia that optimizes maintenance activities while ignoring operational impact.

3.3.2 Engineering staff spot technical gaps.

Design engineers understand equipment capabilities and limitations that maintenance might not fully appreciate.

They can assess whether maintenance strategies align with manufacturer recommendations and industry standards. Reliability engineers bring statistical thinking and failure analysis expertise that deepens root cause identification.

3.3.3 Supply chain representatives illuminate materials management issues.

Procurement staff understand lead times, supplier reliability and inventory economics that maintenance planners may not consider.

Their participation in audits examining parts management and inventory practices produces more actionable findings.

3.3.4 Cross-functional participation builds ownership.

When operations, engineering and supply chain contribute to audits, they own the findings and recommendations.

This ownership increases implementation success rates.

Audit recommendations become shared improvement priorities rather than maintenance asking other departments for favors.

3.3.5 Start with willing participants.

Don’t force cross-functional participation on unwilling departments.

Begin with groups that see value in collaboration, demonstrate the benefits through successful joint audits, then expand participation as word spreads about positive experiences.

3.4 Auditor Training Programs That Work.

Throwing untrained auditors at complex maintenance systems produces superficial, inconsistent results. Effective auditor training combines technical content, interpersonal skills and practical application.

3.4.1 Start with audit fundamentals.

Many potential auditors have never conducted formal audits.

They need foundational concepts: audit purpose and value, ethical conduct expectations, evidence types and quality, documentation standards and reporting protocols. Don’t assume this knowledge, teach it explicitly.

3.4.2 Teach the specific audit framework and criteria your organization uses.

Walk auditors through your criteria documents section by section. Discuss the rationale behind each criterion and its weighting.

Show examples of strong and weak performance for each criterion.

This detailed orientation prevents auditors from imposing their personal standards rather than applying organizational criteria.

3.4.3 Develop questioning skills through practice.

Effective audit questioning doesn’t come naturally to most people. Create practice scenarios where trainees interview role-players about fictional maintenance processes.

Record these practice sessions and review them together, identifying effective questions and missed opportunities.

Focus on open-ended questions, follow-up probes and techniques for overcoming evasive responses.

3.4.4 Practice evidence evaluation and scoring.

Present trainees with sample audit evidence, work orders, procedures, interview transcripts, observation notes and have them independently score scenarios using your criteria.

Compare scores and discuss differences. This calibration exercise surfaces interpretation variances before they occur in real audits.

3.4.5 Shadow experienced auditors.

Classroom training only goes so far. New auditors should participate in several audits alongside experienced team members before conducting solo audits.

Shadowing provides context that classroom discussion can’t replicate, how to navigate facility environments, manage time constraints, handle unexpected discoveries and maintain professional demeanor under challenging conditions.

3.4.6 Provide feedback loops.

After new auditors complete their first independent audits, have experienced auditors review their work.

This review should examine both audit process (did they collect appropriate evidence?) and audit product (are findings clearly stated and well-supported?).

Constructive feedback during early audits prevents bad habits from becoming entrenched.

3.5 Maintaining Auditor Objectivity and Independence.

Auditor objectivity can erode over time.

Organizations need safeguards to maintain independence and prevent conflicts of interest from compromising audit quality.

3.5.1 Rotate audit assignments periodically.

An auditor who examines the same process repeatedly may develop relationships with auditees that compromise objectivity.

They might become blind to persistent issues or hesitant to report findings about people they’ve come to know personally.

Rotating assignments every 2-3 audit cycles prevents excessive familiarity while preserving learning curve benefits.

3.5.2 Avoid auditing areas where you have direct responsibilities.

Maintenance managers shouldn’t audit processes they control. This creates obvious conflicts, they’re essentially evaluating their own work.

Even with good intentions, they’ll struggle to maintain objectivity. Independent auditors from other departments or external consultants should assess areas where conflict potential exists.

3.5.3 Create reporting structures that protect auditors.

If auditors report to the managers whose areas they’re auditing, they face career pressures that undermine candor.

Audit teams should report to organizational levels above the functions being audited, or to independent quality/compliance departments.

This reporting structure protects auditors from retribution when they identify uncomfortable truths.

3.5.4 Separate audit findings from corrective actions.

The person identifying a problem shouldn’t be the same person implementing the fix. This separation preserves auditor independence while ensuring auditees own improvements. Auditors discover and describe; auditees decide how to address findings. This division of responsibilities reduces audit defensiveness.

3.5.5 Watch for “going native” syndrome.

Auditors who spend years examining the same organization gradually adopt that organization’s norms and blind spots.

What initially shocked them becomes normal. Regular calibration against external benchmarks or periodic inclusion of external auditors helps reset perspective and prevents this drift.

4.0 Conducting the Physical Audit.

The rubber meets the road when auditors walk into facilities, open conversations and start examining evidence. This phase transforms preparation into discovery. How you conduct physical audits determines whether you uncover truth or just hear what people want you to hear.

4.1 Pre-Audit Preparation and Communication.

Showing up unannounced might work for surprise regulatory inspections, but it’s terrible strategy for internal improvement audits. Preparation and communication set up successful audits.

1) Send notification at least two weeks ahead: Your notification should specify audit scope, expected duration, key personnel who’ll need to be available and information or documentation you’ll want to review. This advance notice isn’t about giving people time to “clean up”, it’s about respecting their time and ensuring the right people and resources are available.

2) Request specific documentation in advance: Rather than asking “Can we see your procedures?” request specific documents: “Please provide copies of your work planning procedure, last six months of backlog reports and samples of 10 planned work orders from the past 30 days.” Specificity helps auditees gather what you need and reduces time spent hunting for documents during the audit.

3) Identify your evidence sampling strategy: Before arriving, determine how you’ll select work orders, equipment records or other items for examination. Random sampling reduces selection bias. Stratified sampling ensures you examine examples from different equipment types, work priorities or time periods. Document your sampling method so findings can’t be dismissed as cherry-picking.

4) Review previous audit findings: If this isn’t your first audit of this area, review prior findings and verify whether corrective actions were implemented. This historical context helps you assess improvement trajectory and identify recurring issues that previous fixes didn’t actually resolve.

5) Prepare your audit checklist and tools: Convert your audit criteria into a structured checklist that ensures consistent evidence collection. Bring tools you’ll need, camera for documenting conditions, tablet or laptop for real-time documentation, voice recorder if you’ll record interviews, measuring devices if you’ll verify physical conditions.

4.2 Opening Meetings That Set the Right Tone.

The first 15 minutes of an audit set the emotional tone for everything that follows. Get this wrong and you’ll spend the rest of the audit fighting defensive reactions.

1) Start with purpose, not process:

a. Begin by reminding everyone why audits exist:

i. “We’re here to help identify opportunities for improvement and share best practices.

ii. This isn’t about finding fault, it’s about discovering what’s working well and where small changes could deliver big benefits.”

b. Mean it when you say it. If your tone, body language or word choices contradict this message, people will trust the nonverbal signals over your words.

2) Acknowledge the disruption:

a. “I know audits take time away from your regular work. We appreciate you making room for this and we’ll do our best to be efficient with everyone’s time.”

b. This acknowledgment shows respect and builds cooperation.

3) Explain what you’ll do and what you need from them:

a. Walk through your planned activities:

i. “Today we’ll spend about an hour touring the facility, interview about six people for 20-30 minutes each and review a sample of work orders and procedures.

ii. Tomorrow we’ll wrap up any loose ends and have a brief closeout meeting to share preliminary findings.”

b. Clear expectations reduce anxiety.

4) Clarify confidentiality and attribution:

a. Tell people how you’ll handle sensitive information:

i. “Specific comments won’t be attributed to individuals in our report.

ii. We’re looking for patterns across multiple sources, not calling out specific people.”

b. This assurance encourages honesty.

5) Invite questions and concerns:

a. “Before we start, what questions or concerns do you have about the audit?”

b. Sometimes people need to voice anxiety before they can move past it. Address concerns directly and honestly.

c. If you can’t promise something, don’t. Better to disappoint upfront than lose credibility later.

6) Watch for emotional temperature:

a. If the room feels tense, slow down.

b. If someone seems particularly anxious or hostile, acknowledge it:

i. “I sense some concern. Want to talk about what’s on your mind?”

c. Sometimes simply naming the elephant in the room reduces its power.

4.3 Evidence Gathering Techniques.

Effective evidence gathering blends multiple techniques, each revealing different aspects of reality. Strong auditors know when to use each approach and how to synthesize varied evidence types into coherent findings.

4.3.1 Document review reveals what’s supposed to happen.

Start with procedures, standards and documented processes.

These documents represent the organization’s stated intent.

However, don’t stop there, the gap between documented and actual practice often contains your most important findings.

As you review documents, note questions to explore during interviews: “This procedure says supervisors approve all work orders before release, but how consistently does that actually happen?”

4.3.2 Interviews uncover how things actually work.

Talk to people at multiple organizational levels, managers explain strategy, supervisors describe coordination challenges, technicians reveal ground-level reality. The magic happens when you compare these perspectives.

Managers might believe planners provide comprehensive work packs; technicians might report receiving minimal documentation. This gap matters more than either perspective alone.

4.3.3 Physical observations catch what people don’t tell you.

Walk through maintenance areas and watch work happening.

Are tools organized and accessible? Do work orders accompany technicians or sit on clipboards elsewhere?

When technicians pick up work orders, do they read them carefully or glance and ignore? These observations reveal cultural realities that interviews might miss.

4.3.4 CMMS data analysis quantifies patterns.

Pull reports on work order completion times, PM compliance rates, backlog age, planner productivity and other metrics.

Numbers provide objectivity that qualitative evidence lacks.

They also reveal trends invisible in individual examples, one late work order is an anecdote, 40% of work orders exceeding planned completion dates is a pattern requiring explanation.

4.3.5 Photographic evidence documents conditions.

Pictures capture physical realities, cluttered work areas, missing safety equipment, deteriorated assets, well-organized tool rooms, excellent visual management.

Photos also protect you from “that’s not how it usually looks” responses. You documented what you saw when you saw it.

4.3.6 Sampling strategies determine representativeness.

You can’t examine every work order or interview every employee.

Your sampling approach determines whether findings reflect typical performance or exceptional cases. Random sampling prevents cherry-picking.

Stratified sampling ensures coverage across equipment types, work categories or time periods. Document your sampling method in your report so readers understand the basis for your conclusions.

4.4 Real-Time Documentation Methods.

Waiting until after the audit to document findings is a recipe for forgotten details, lost context and reconstruction errors. Document as you go, using approaches that capture information without disrupting audit flow.

1) Use structured note templates:

a. Create templates for each evidence type, interview notes, observation records, document review findings.

b. Templates ensure you capture essential information consistently and reduce cognitive load during evidence collection.

c. Your interview template might include fields for: interviewee name/role, date/time, key topics discussed, direct quotes (in quotation marks), your observations (clearly labeled as such) and follow-up questions.

2) Distinguish facts from interpretations:

a. In your notes, separate what you observed or were told from your interpretation.

b. Use different formats, facts in regular text, interpretations in italics or brackets.

c. This distinction preserves evidence integrity and prevents premature conclusions from contaminating raw data.

d. “The Planner/Scheduler stated that work orders are released to the schedule one week in advance [FACT].

e. This suggests planning is happening too late to support effective scheduling [INTERPRETATION].”

3) Record direct quotes liberally:

a. When someone says something particularly telling, capture their exact words in quotation marks.

b. Direct quotes add power to findings: “As one technician explained, ‘I stopped reading the work order details because they’re usually wrong anyway. I just look at the equipment number and figure out what needs doing.'” That quote reveals more about planning quality than paragraphs of analysis.

4) Take photos with context:

a. Don’t just photograph problems, photograph the surrounding area so viewers understand context.

b. If you’re documenting poor parts storage, capture wide shots showing the full storage area plus close-ups of specific issues.

c. Add brief captions to photos immediately so you remember what you were trying to show.

5) Use audio recording when appropriate:

a. Some auditors record interviews (with permission), allowing them to maintain eye contact and engagement rather than frantically scribbling notes.

b. Recordings provide verbatim records and protect against misquotes. However, recordings can inhibit candor, some people self-censor when they know they’re being recorded.

c. Read the room and decide whether recording helps or hinders.

6) Time-stamp everything:

a. Note the date and time when you collected each piece of evidence.

b. This timestamp provides context (was this during normal operations or a maintenance shutdown?) and demonstrates thoroughness if findings are later challenged.

7) Review notes daily:

a. At the end of each audit day, review your notes while memories are fresh.

b. Clarify cryptic shorthand, add context you didn’t have time to capture during collection and identify gaps requiring follow-up the next day.

c. Waiting until the audit concludes to review notes guarantees you’ll forget critical details.

4.5 Managing Difficult Conversations During Audits.

Not every audit conversation flows smoothly. People become defensive, hostile, evasive or emotional. Skilled auditors navigate these difficult moments without derailing the audit or damaging relationships.

1) Recognize defensiveness for what it is: When someone reacts defensively to questions, getting argumentative, making excuses, deflecting blame elsewhere, they’re usually feeling threatened. The defensive response is about protecting themselves, not attacking you. Understanding this helps you respond with curiosity rather than matching their emotional intensity.

2) Lower the temperature with empathy: “I can tell this topic is frustrating for you” or “Sounds like you’re dealing with some real constraints here” acknowledges their experience without agreeing or disagreeing with their perspective. This acknowledgment often reduces defensiveness because the person feels heard.

3) Separate the person from the system: When you encounter poor performance, frame it as a system issue rather than personal failure: “It sounds like the current process makes it really hard to complete PMs on time. What obstacles get in the way?” This framing invites problem-solving rather than triggering defensiveness.

4) Use the “help me understand” technique: When you hear something that doesn’t make sense or seems problematic, respond with genuine curiosity: “Help me understand how that works” or “Walk me through what happens when…” These phrases feel less confrontational than “why” questions, which can sound accusatory.

5) Don’t argue with audit subjects: Your job is gathering information, not winning debates. If someone disagrees with your observations, note their perspective without defending your position: “I hear you saying that work orders usually contain adequate information. I’ve noted that feedback. Can you help me understand why the technicians I spoke with expressed different experiences?” You’re documenting multiple perspectives, not determining truth in real-time.

6) Know when to take a break: If a conversation becomes heated, pause it: “I can see we’re both feeling some frustration here. How about we take a 10-minute break and come back to this?” Breaks give everyone time to regulate emotions and reconsider approaches.

7) Escalate when necessary: Occasionally you’ll encounter outright hostility or refusal to cooperate. Don’t try to power through, involve leadership: “It seems like there’s significant concern about this audit. Would it help to bring in [manager name] to discuss how we can proceed productively?” Leadership involvement usually resolves obstruction quickly.

8) Document resistance itself: If someone refuses to provide requested information or actively obstructs the audit, that behavior is itself a finding. Document it factually: “Requested access to backlog reports for Q3 and Q4. Supervisor stated these reports exist but declined to provide them, citing concerns about how data might be interpreted.” Leadership needs to know about obstructionist behavior.

5.0 Mastering the Art of Audit Questioning.

Questions are an auditor’s primary tool. The difference between superficial and insightful audits often comes down to questioning technique.

Poor questions yield surface-level answers that confirm what people want you to believe. Great questions uncover reality.

5.1 Why Most Auditors Ask Terrible Questions.

Most auditors ask yes/no questions that are easy to answer but reveal little: “Do you conduct pre-job briefings?”

The respondent says yes, the auditor checks a box and they move on.

This exchange confirms that pre-job briefings are supposed to happen but reveals nothing about whether they actually occur, how effective they are, or what barriers prevent consistent execution.

1) Leading questions telegraph desired answers: “You do follow the lockout procedure every time, right?” This question practically begs for a yes response. The auditor has signaled what they want to hear and most people accommodate. You’ve learned nothing except that the respondent understood your expectations.

2) Compound questions confuse respondents: “How do you identify, prioritize and schedule corrective work?” That’s actually three different questions. Respondents often answer whichever piece they find easiest or most comfortable, leaving other parts unaddressed. Ask one question at a time.

3) Jargon-filled questions assume shared understanding: “How does your FMECA process integrate with PM strategy development?” If the respondent doesn’t fully understand FMECA or its connection to PM strategy, they might bluff their way through an answer rather than admit confusion. You’ll get a response, but not necessarily an accurate one.

4) Questions without follow-up accept surface answers: Someone tells you “We do that” and you move on. Skilled auditors recognize that “we do that” could mean “we always do that exactly as written,” “we sometimes do that when circumstances allow,” or “we did that once three years ago.” The initial answer is just the starting point.

5.2 The STAR Technique for Behavioral Auditing.

STAR (Situation, Task, Action, Result) is a powerful technique borrowed from behavioral interviewing that reveals how processes actually work rather than how people think they’re supposed to work.

Situation: “Tell me about the last time you had to plan emergency work on a critical asset.”

1) Task: “What did that planning process require you to do?”

2) Action: “Walk me through exactly what you did, step by step.”

3) Result: “How did that work out? What went well? What could have gone better?”

This sequence forces respondents to describe specific instances rather than generalizations.

You’re not asking “How do you plan emergency work?” (which invites textbook answers), you’re asking them to recount a real experience.

The details they include and omit reveal actual practice.

1) Probe for specifics when answers stay general: If someone says “We always check inventory before scheduling work,” respond with “Tell me about the last work order where you found parts weren’t available. What happened?” Specific examples either support or contradict general claims.

2) Ask for recent examples: “Tell me about an example from the last week” produces more reliable information than “tell me about a time when…” which allows respondents to reach back for their best example rather than typical practice.

3) Listen for inconsistencies: When someone’s specific example contradicts their general claim, they say “we always do X” but their example shows they didn’t do X, you’ve found something interesting. Explore the gap gently: “That’s helpful. So in that specific case, X didn’t happen. What prevented it?”

5.3 Following the Evidence Trail.

Auditing is detective work. Each piece of evidence generates new questions that lead you deeper into understanding system realities. Skilled auditors follow these trails wherever they lead.

1) When you hear “we’re supposed to…” ask “What actually happens?”

a. The gap between supposed-to and actually-does contains important information.

b. Sometimes the gap exists because procedures are unrealistic or outdated. Sometimes it’s because accountability is lacking.

c. Sometimes it’s because people don’t have the tools or training they need.

d. Each explanation points to different solutions.

2) When you see disconnects between data sources, investigate why:

a. CMMS reports show 95% PM compliance, but technicians tell you they regularly skip tasks.

b. These can’t both be true. Is someone marking work complete without doing it? Are tasks being performed but not the full scope?

c. Is the CMMS measuring something different than what technicians understand as “completion”?

d. Follow the trail until you understand the disconnect.

3) When someone says “it depends,” dig into what it depends on:

a. This phrase signals that process execution is inconsistent or conditional.

b. “It depends” on what factors? Who decides? Are those factors documented?

c. Understanding what drives variability helps you assess whether that variability is appropriate response to different circumstances or problematic inconsistency.

4) When you encounter workarounds, explore why they exist:

a. Workarounds signal that formal processes aren’t working.

b. Someone developed an unofficial better way.

c. Rather than just noting that the formal process isn’t followed, understand what makes the workaround necessary.

d. Often you’ll discover that the workaround is actually superior to the formal process, suggesting the formal process needs updating rather than enforcement increasing.

5) Follow the “five whys” principle:

a. When you identify a problem, ask why it happens.

b. Then ask why that reason exists. Keep asking why until you reach root causes.

c. Surface causes like “technicians don’t complete PM tasks” might trace back through “tasks take longer than scheduled time allows” and “time estimates weren’t based on actual performance data” to ultimately reveal “we don’t have a process for updating PM task times based on execution feedback.”

5.4 Detecting Social Desirability Bias.

People want to look good. They tell auditors what they think the auditor wants to hear, what makes them look competent, or what matches official policy.

This social desirability bias skews audit evidence if you don’t account for it.

1) Watch for consistently positive responses.

a. If every answer to your questions is “yes, we do that well,” you’re probably not hearing truth.

b. Real-world processes have weaknesses.

c. Perfect or near-perfect responses signal that you’re getting filtered information rather than honest assessment.

2) Listen for hedging language.

a. Words like “usually,” “mostly,” “generally,” “typically” and “for the most part” signal variability.

b. When someone says “We generally complete PMs on time,” they’re actually telling you “sometimes we don’t.”

c. Follow up: “When PMs don’t get completed on time, what’s usually happening?”

3) Compare what people say with what data shows.

a. People’s perceptions often differ from quantitative reality.

b. A supervisor might genuinely believe they’re completing 90% of planned work when data shows 60% completion.

c. The supervisor isn’t lying, they’re remembering recent successes more vividly than chronic incompletions.

d. Data provides the reality check.

4) Notice what people volunteer versus what they reveal reluctantly:

a. Information offered freely tends to be positive or neutral.

b. Negative information usually requires direct questioning.

c. If you have to pull teeth to get basic information, you’re encountering reluctance worth exploring: “I notice you seem hesitant to discuss this. What makes this topic challenging to talk about?”

5) Ask the same question to multiple people at different levels:

a. If managers, supervisors and technicians all describe a process identically, it’s probably accurate.

b. If their descriptions vary significantly, you’re likely hearing different perspectives or different realities.

c. Senior leaders sometimes describe the world as they wish it were or as they’ve been told it is.

d. Front-line workers describe the world they actually experience.

5.5 When to Push and When to Pivot.

Knowing when to press for more information and when to move on separates skilled auditors from mediocre ones.

Push too hard and you damage relationships. Move on too quickly and you miss critical insights.

1) Push when you sense you’re close to important information: Body language often telegraphs significant information, someone pauses before answering, makes eye contact with a colleague, or shifts their tone. These signals suggest you’re approaching something meaningful. Gentle persistence often yields breakthroughs: “I sense there’s more to this story. What am I missing?”

2) Push when answers don’t add up: If someone’s explanation contradicts evidence you’ve already gathered, probe the inconsistency: “That’s interesting. The data I’ve seen suggests something different. Help me understand where my interpretation might be off.” This framing invites clarification without accusing anyone of dishonesty.

3) Push when you get vague generalities instead of specifics: Vague answers often hide uncomfortable realities. “Can you give me a specific example of that?” or “What does that look like in practice?” moves conversations from comfortable abstractions to revealing specifics.

4) Pivot when emotional temperature rises too high: If someone becomes visibly distressed or angry, continuing to push damages your ability to gather information from them and others. “Let’s come back to this topic later” preserves the relationship while signaling the topic isn’t closed.

5) Pivot when you’re not getting new information: If you’ve asked the same question three different ways and keep getting essentially the same answer, you’ve likely extracted what this person knows or is willing to share. Move on and try another information source.

6) Pivot when time constraints require it: Audits have limited time. If you’ve spent 20 minutes exploring a secondary topic, you may need to cut that conversation short to ensure you cover primary audit areas. “This is fascinating and I’d love to explore it more, but I want to make sure we cover the other areas I need to assess. Can we move to…?”

6.0 Documenting Findings That Drive Action.

Audit findings that languish unaddressed waste everyone’s time and undermine future audit credibility.

How you document findings largely determines whether they produce action or just add to a pile of ignored reports.

6.1 Writing Findings That Can’t Be Ignored.

Weak finding: “Work planning needs improvement.”

Strong finding: “Only 23% of sampled work orders included complete parts lists. Technicians reported needing to make an average of 2.3 trips to the storeroom per job to retrieve parts not identified during planning. This inefficiency reduced wrench time by approximately 18% based on time study observations.”

What makes the second finding compelling? It’s specific, quantified, connects to observable impact and leaves little room for debate. Leaders reading this finding immediately understand the problem’s magnitude and business impact.

1) State what you observed, not what you conclude:

a. Findings should describe observable facts rather than jumping to solutions or judgment.

b. “The current process lacks adequate controls” is a conclusion.

c. “Three of the five supervisors interviewed were unaware that work order approval is required before releasing work to technicians” is an observation that readers can evaluate themselves.

2) Quantify whenever possible:

a. Numbers transform subjective impressions into objective evidence.

b. Rather than “many work orders,” say “47 of 60 sampled work orders (78%).”

c. Rather than “significant delays,” say “average completion time of 23 days against planned completion time of 12 days.”

d. Numbers make findings concrete and measurable.

3) Link findings to business impact:

a. Leaders care about audit findings to the extent those findings affect things they care about, safety, reliability, cost, compliance.

b. Make those connections explicit: “This documentation gap creates regulatory compliance risk. Our operating permit requires maintaining equipment maintenance records for seven years. The current practice of storing completed work orders in supervisors’ offices rather than archiving them systematically means 40% of records from 2020-2022 could not be located during the audit.”

4) Provide specific examples:

a. General statements feel abstract.

b. Specific examples make findings real: “Work order #45891 scheduled for completion on June 15 remained open on August 3 (49 days overdue) with no notes explaining the delay or updated target completion date.”

5) Distinguish between isolated instances and patterns:

a. One example could be an anomaly.

b. Multiple examples suggest systemic issues.

c. Your finding should clarify: “This issue appeared in 34 of 50 sampled work orders, suggesting a systemic pattern rather than isolated incidents.”

6.2 Classifying Finding Severity Appropriately.

Not all findings matter equally. Your classification system should help readers quickly distinguish between critical issues requiring immediate attention and minor opportunities for incremental improvement.

1) Critical findings threaten safety, create imminent risk of major equipment failure, violate legal or regulatory requirements, or enable fraud/theft. These demand immediate corrective action, often with interim controls implemented before the audit even concludes. Example: “Locked-out equipment was observed with locks missing from three of seven required isolation points. Operations personnel confirmed the equipment could be inadvertently energized in this state, creating serious injury risk.”

2) Major findings significantly impact operations, create elevated risk, demonstrate widespread process failures, or indicate major gaps between documented procedures and actual practice. These require formal corrective action plans with defined timelines. Example: “Analysis of 100 preventive maintenance work orders found that 62% were marked complete with actual task durations less than 50% of planned task time. Interviews with technicians revealed routine practice of marking PMs complete without performing all tasks.”

3) Minor findings represent opportunities for improvement without creating immediate risk or significant operational impact. These might be addressed through informal coaching, procedure clarification, or inclusion in routine improvement activities. Example: “Work order closure notes were absent or brief (fewer than 10 words) in 30% of sampled work orders, limiting their value for future reference.”

4) Observations note practices that aren’t necessarily problems but differ from common industry practice or could be enhanced. These don’t require corrective action but might spark improvement discussions. Example: “The facility uses monthly planning cycles, whereas weekly planning cycles are more common in similar operations and could provide greater scheduling flexibility.”

5) Apply classification criteria consistently:

a. Create written standards defining each severity level with examples. Calibrate auditors to apply classifications consistently.

b. Inconsistent severity assignments undermine credibility and make prioritization difficult.

6.3 Linking Findings to Business Impact.

Leaders drowning in competing priorities need to understand why they should care about your findings.

Connecting audit findings to business outcomes they’re measured on increases action probability dramatically.

1) Translate findings into financial terms when possible: “Inefficient work planning” is abstract. “Poor planning practices cost an estimated $340,000 annually in excess labor hours and duplicate trips” gets attention. Even rough estimates based on reasonable assumptions beat vague statements about “wasted resources.”

2) Connect findings to strategic initiatives: If your organization has committed to reducing unplanned downtime by 30%, show how audit findings affect that goal: “The absence of condition-based maintenance for critical pumps directly contradicts the site’s reliability improvement strategy. Based on failure patterns over the past 18 months, implementing vibration monitoring on these assets could prevent an estimated 60-80 hours of unplanned downtime annually.”

3) Highlight compliance and risk exposures: Leaders care deeply about regulatory compliance and risk management because personal and organizational consequences can be severe. Make these connections explicit: “The gap in hazardous energy control documentation creates OSHA citation risk. Similar violations at comparable facilities have resulted in penalties ranging from $7,000 to $70,000 per citation.”

4) Show how findings affect other departments: Maintenance issues often impact production, quality, safety and customer service. Making these cross-functional connections builds broader support for addressing findings: “Late maintenance completion on packaging lines has caused operations to miss production targets in 7 of the past 12 weeks, contributing to customer delivery delays that sales has flagged as account relationship concerns.”

5) Use comparative language: Help readers understand relative performance: “Current PM compliance of 72% falls below the industry benchmark of 85-90% for facilities of similar size and complexity. This gap suggests approximately 150-200 maintenance tasks that should have occurred didn’t happen.”

6.4 Photographic Evidence and Work Samples.

Pictures, screenshots and document samples bring findings to life in ways that text descriptions can’t match.

Visual evidence makes abstract findings concrete and memorable.

1) Photograph conditions systematically: Don’t just capture problems, photograph the full context. If you’re documenting cluttered tool storage, show wide shots of the entire area plus close-ups of specific problematic sections. Context prevents readers from dismissing photos as unrepresentative cherry-picking.

2) Include work samples liberally: Rather than describing poor work order quality in text, include screenshots or photocopies of actual work orders (with sensitive information redacted). Readers seeing actual examples understand issues more deeply than reading descriptions.

3) Use before/after comparisons when possible: If you’re conducting follow-up audits, showing before and after states visually demonstrates improvement or lack thereof. “Work order quality improved” becomes much more convincing when accompanied by side-by-side examples.

4) Add clear captions: Don’t assume visual evidence speaks for itself. Captions should explain what you want readers to notice: “Missing equipment tag makes asset identification difficult. Technician reported spending 15 minutes locating correct asset among similar-looking pumps.”

5) Annotate images to highlight key points: Add arrows, circles or callout boxes to direct attention to specific elements. An unmarked photo of an equipment room might not convey the issue you’re highlighting. The same photo with an arrow pointing to missing safety equipment and a caption makes your finding unmistakable.

6) Respect privacy and sensitivity: Don’t include recognizable faces without permission. Avoid capturing information that could compromise security. If you’re photographing work order content, redact names and potentially sensitive technical details. The goal is illustrating your finding, not embarrassing individuals or exposing confidential information.

6.5 Creating Finding Statements That Survive Challenges.

Your findings will be questioned. Defensive stakeholders will push back, minimize significance, or argue your interpretation is wrong. Findings that survive these challenges share specific characteristics.

1) Root findings in objective, verifiable evidence: Opinions can be dismissed. Facts backed by documentation, system data, or multiple corroborating interviews are much harder to refute. “Planning quality is poor” invites debate. “Analysis of 50 planned work orders found 37 (74%) lacked complete parts lists, confirmed by interviews with 8 technicians who reported routinely needing parts not identified during planning” is defensible.

2) Acknowledge limitations and context: Perfect confidence invites skepticism. Acknowledging limitations actually increases credibility: “This finding is based on a sample of work orders from Q2 and Q3. Performance may differ in other time periods. However, the pattern was consistent across both months sampled and matched descriptions provided by multiple interviewees.”

3) Separate facts from recommendations: Findings should describe current state and its impacts. Recommendations suggest potential solutions. Keeping these separate allows stakeholders to agree with your assessment even if they disagree with your recommendations. They can’t argue against what you observed, only how they choose to address it.

4) Use neutral, professional language: Avoid emotional or inflammatory language that triggers defensiveness. “The maintenance team is lazy” will provoke arguments. “Task completion rates below planned expectations suggest barriers to effective execution that merit investigation” opens dialogue about root causes rather than assigning blame.

5) Provide sufficient detail to allow verification: Readers should be able to check your work. Include details like work order numbers, dates, names of people interviewed (unless confidentiality precludes this), specific procedures referenced and data queries used. This transparency demonstrates thoroughness and allows others to verify your findings if challenged.

6) Anticipate counterarguments: Think about how findings might be challenged and address potential objections preemptively: “While supervisors reported that work orders are always reviewed before release, system data shows 28% of work orders transition directly from ‘Planning Complete’ to ‘Released’ status without any timestamp in the ‘Supervisor Review’ field, suggesting the review step is bypassed for a significant portion of work.”

7.0 Turning Audit Results Into Improvement Plans.

Audit reports that gather dust on shelves represent wasted effort. The value of auditing lies in spurring improvement.

Converting findings into action requires deliberate planning, clear accountability and sustained follow-through.

7.1 Prioritization Frameworks for Findings.

You’ll typically identify more issues than you can address simultaneously.

Prioritization frameworks help allocate scarce improvement resources where they’ll deliver maximum value.

1) Risk-based prioritization evaluates findings on two dimensions: consequence (what happens if we don’t fix this?) and likelihood (how often is this issue occurring or likely to occur?). Plot findings on a risk matrix. High consequence, high likelihood findings obviously demand immediate attention. Low consequence, low likelihood findings might be deferred indefinitely. The tougher calls involve high consequence/low likelihood (rare but potentially catastrophic) and low consequence/high likelihood (frequent but minor) findings.

2) Resource-intensity consideration acknowledges that some fixes are quick wins while others require significant investment. Map findings on a second dimension: impact versus effort. High-impact, low-effort improvements should be tackled first, they demonstrate quick progress and build momentum. High-impact, high-effort improvements require formal project management but warrant the investment. Low-impact improvements, regardless of effort, should generally be deprioritized until higher-value opportunities are exhausted.

3) Strategic alignment asks which findings most directly support organizational strategic goals. If asset life extension is a strategic priority, findings related to condition monitoring and predictive maintenance deserve higher priority than findings about administrative documentation gaps. Linking improvements to strategy secures leadership support and resources.

4) Cumulative impact analysis recognizes that some findings cluster around common root causes. Addressing a single root cause might resolve multiple surface-level findings. Look for these opportunities: “Five separate findings relate to CMMS data quality. Rather than addressing each individually, implementing a comprehensive data governance program would resolve all five while preventing future data quality issues.”

5) Quick wins versus strategic improvements: Balance your improvement portfolio between quick wins that deliver visible short-term progress and strategic improvements that require longer timelines but create lasting change. All quick wins and no strategic work produces temporary improvements without systemic change. All strategic work and no quick wins creates frustration as people wait months or years to see results.

7.2 Assigning Ownership and Accountability.

Findings without clear owners rarely get resolved. Vague collective responsibility typically means nobody actually owns the problem.