Process-Linked Maintenance Strategies

Disclaimer.

This article provides general information about asset management practices, CMMS, EAM and ERP system configuration in lithium mining contexts.

It is not professional advice and should not be used as the sole basis for technology selection, maintenance strategy design, or regulatory decision‑making.

Lithium projects vary significantly by jurisdiction, extraction method, water regime, Environmental, Social & Governance (ESG) commitments and risk appetite, so readers should seek qualified advice and verify all practices against current standards, contracts and regulatory requirements.

Any thoughts, views, ideas and opinions expressed are those of the author only.

No warranty is provided regarding the accuracy, completeness, or applicability of this information to any specific operation. The author assumes no liability for actions taken based on this content.

Article Summary.

Lithium operations amplify the weaknesses of generic maintenance strategies because their degradation mechanisms, locations and regulatory expectations diverge sharply from average industrial assumptions.

Brine evaporation facilities operate with extremely high salinity and complex ion chemistry that drive corrosion, mineral scaling and sensor fouling far beyond what conventional PM templates anticipate.

Hard‑rock spodumene mines face highly abrasive, hardness‑driven wear in crushers, mills and conveying systems, where ore variability materially changes component life.

Remote locations and fragile telecommunications infrastructure make connectivity‑dependent workflows unreliable, especially for mobile work execution.

At the same time, lithium’s ESG profile attracts intense scrutiny of water usage, emissions and land disturbance, which demands EAM data structures aligned with region‑specific regulatory reporting.

Organizations that deploy ‘vanilla’ asset management configurations in this context tend to experience inflated reactive maintenance, unreliable forecasts and weak compliance evidence.

Those that deliberately align their asset strategies, master data and workflows with lithium‑specific conditions see more stable availability, lower lifecycle cost and more robust ESG reporting.

Top 6 Takeaways.

1. Lithium extraction environments have degradation mechanisms that diverge from generic industrial assumptions, so standard PM libraries and task templates are usually mis-calibrated.

2. Brine and hard‑rock operations require maintenance strategies grounded in chemistry, geology and variable operating conditions, not just OEM intervals.

3. Remote, infrastructure‑poor locations make offline‑first work execution and resilient data synchronisation essential design principles.

4. ESG and environmental monitoring expectations around water, emissions and land use require asset management structures built around specific jurisdictional reporting needs.

5. Aligning asset management configuration with lithium‑specific realities should help to improve availability, cost control and regulatory defensibility.

6. Integrated operational technology stacks beneficial for process‑linked maintenance, requiring DCS, historian, OMS, CMMS/EAM/ERP systems to work together to reflect real degradation drivers.

Table Of Contents.

1.0 Introduction.

2.0 Why Generic Maintenance Strategies Might Miss the Mark.

2.1 Misaligned Degradation Assumptions.

2.2 Master Data Structures That Ignore Chemistry and Geology.

2.3 Connectivity Dependent Workflows in Remote Locations.

2.4 ESG and Compliance Structures.

3.0 Operational Realities That Drive Failures.

3.1 Brine Evaporation: Chemistry Driven Degradation.

3.2 Hard Rock Spodumene: Abrasive, Hardness Driven Wear.

3.3 Remote Locations and Fragile Infrastructure.

3.4 Regulatory and ESG Intensification

4.0 Strategic Implications for Leaders.

4.1 Maintenance and Reliability Leadership.

4.2 Operations and Production Leadership.

4.3 CIOs and Technology Strategy.

4.4 Organisational Readiness and Change.

5.0 Enabling Technology for Process Linked Maintenance Strategies.

5.1 Core Technology Components.

5.1.1 Process Historian (AVEVA PI System).

5.1.2 Distributed Control System (Yokogawa CENTUM VP).

5.1.3 Operations Management System (OMS).

5.2 OMS Setup for Lithium Operations.

5.3 Integration Architecture to CMMS/EAM/ERP.

5.4 What an Integrated System Looks Like.

6.0 Terms and Abbreviations Used.

7.0 Conclusion.

1.0 Introduction.

Lithium has become a cornerstone mineral for batteries and

energy storage however, its extraction environments sit at the edge of what

many generic asset management implementations were originally designed to

handle.

Leaders across maintenance, operations and technology often

ask the same difficult questions such as:

1. Why do generic maintenance/asset

management strategies fail sometimes in lithium environments?

2. Why do standard PM

templates misjudge degradation?

3. Why do data

structures that work in other industries fall a bit short under lithium’s

chemistry, geology and ESG pressures?

This article does its best to shed some light on these

questions by examining the physical, operational and regulatory realities that

shape lithium extraction.

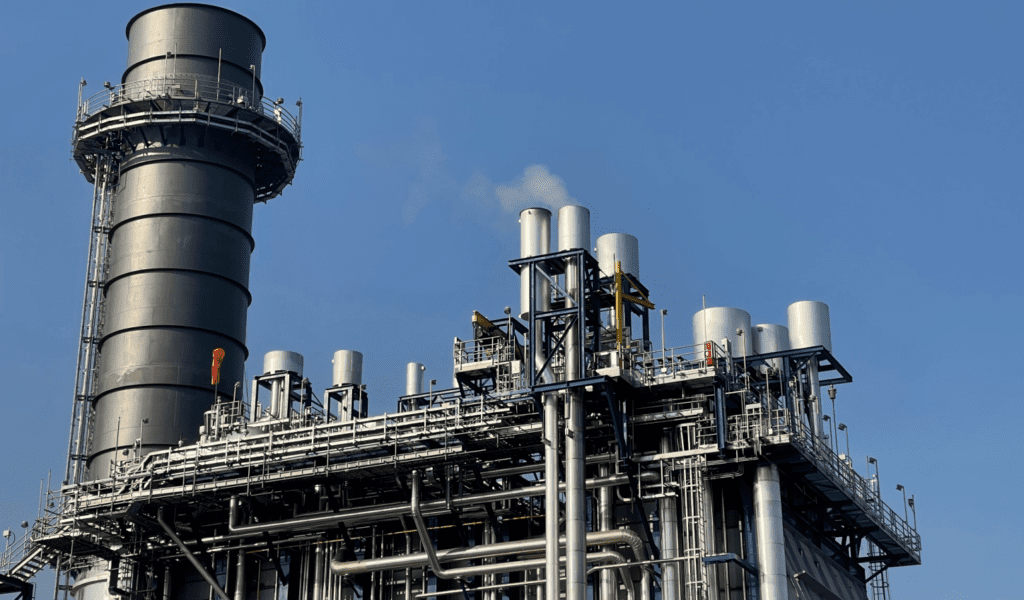

Brine operations and hard rock spodumene mines stress

equipment through combinations of chemical attack, scaling, abrasive wear and

thermal cycling that are not reflected in industry neutral asset management

templates.

As a result, the challenge is not that the commodity itself

changes the CMMS/EAM/ERP software, but that the extraction context invalidates

the assumptions baked into generic asset management strategies that would lie

within. Brine systems handle high salinity fluids with complex mixtures of

sodium, calcium, magnesium and other ions, which drive aggressive scaling and

corrosion in pumps, pipelines and evaporation equipment.

Hard rock circuits process ores with moderate to high

hardness and significant abrasiveness, creating demanding conditions for

crushers, mills and classification equipment.

These environments tend to push maintenance teams to

prioritise different inspection triggers, condition indicators and spare part holding

policies than those found in standard PM setups.

At the same time, lithium projects often sit in remote

basins, deserts or high altitude regions with limited grid power, constrained

logistics and patchy telecommunications.

ESG expectations and water related scrutiny are also higher

than in many conventional commodities because of the perceived footprint of

both brine evaporation and emerging direct lithium extraction technologies.

The result is a context where maintenance strategies should

be deliberately tuned to local realities rather than treated as generic, drop

in data.

2.0 Why Generic Maintenance

Strategies Might Miss The Mark.

Generic maintenance strategies are usually built on three

implicit assumptions:

1. That degradation

patterns are broadly predictable.

2. That connectivity is

reliable.

3. That regulatory

reporting needs are generic and minimal.

Lithium mining seems to undermine all three.

2.1 Misaligned Degradation

Assumptions.

In high‑salinity brines, dissolved solids can reach levels

far above typical industrial water systems and divalent cations such as calcium

and magnesium strongly promote scaling on heat transfer surfaces and flow

paths.

This environment accelerates corrosion of metallic

components and can drastically shorten the effective life of pump internals,

valves, level instrumentation and evaporator surfaces compared with ‘standard’

water service. Generic maintenance

strategies that assume slow, linear degradation and mild service conditions

therefore under‑specify inspection frequencies, cleaning intervals and

component change‑out rules.

In hard‑rock spodumene operations, the primary stressors are

ore hardness, abrasiveness and high‑energy comminution (the process of crushing

and grinding rock to reduce its size).

Variations in ore characteristics between benches or phases

can materially change crusher liner life, mill media consumption and conveyor

wear rates, even when nominal throughput is constant.

Maintenance strategies that assume a fixed interval for

liner changes or fully rely on OEM running‑hour guidance often either over‑maintain

or suffer unexpected failures when the ore feed changes.

2.2 Master Data Structures

That Ignore Chemistry And Geology.

Generic master data configurations frequently treat

equipment purely as mechanical assets, with attributes like manufacturer, model,

serial number and runtime statistics, but no systematic linkage to brine

chemistry, ore type, or process conditions.

In lithium environments, however, variables such as ion

composition, saturation indices, ore hardness, grind size and process

temperature materially influence failure modes.

Without data integrations/interfaces and functionality to

store, relate and trend these variables alongside maintenance histories, the

system might not support meaningful predictive or condition‑based strategies.

For example, correlating pump seal failures with brine

composition and operating temperature can reveal when chemistry shifts demand

changes in materials, filtration, or dosing strategies.

Similarly, linking crusher wear to ore hardness and

throughput can support dynamic adjustment of liner change‑out thresholds and

spares stocking levels.

Generic templates generally do not anticipate these

correlations and therefore fail to provide the fields and workflows needed to

exploit them.

2.3 Connectivity Dependent

Workflows In Remote Locations.

Many lithium projects, including those in remote regions of

Australia, operate far from established infrastructure with limited terrestrial

telecommunications and variable power reliability.

These conditions create a few challenges for cloud first

CMMS deployments that assume continuous connectivity.

Mobile technicians and contractors often need to execute and

close work orders in the field, yet cannot rely on stable online access.

When connectivity is intermittent, devices used to access

CMMS, EAM, or ERP information must allow users to continue working offline.

They need to store all data entered locally and then upload

it automatically once a connection becomes available.

This capability is essential for maintaining accurate work

execution records, asset history, and parts transactions.

Offline first design, supported by robust local caching and asynchronous synchronisation, becomes a

foundational requirement rather than an optional enhancement.

Without it, work execution slows, data becomes fragmented,

and maintenance teams lose confidence in the system’s reliability.

Generic strategies that do not anticipate connectivity

constraints tend to degrade into inconsistent processes and poor data quality.

Lithium operations that adopt offline first architectures

maintain continuity in field execution and preserve the integrity of their

asset information despite the limitations of remote environments.

2.4 ESG And Compliance

Structures.

Lithium’s role in the energy transition places exceptional

focus on water balances, emissions and community impacts, which translates into

demanding monitoring and reporting expectations.

Brine operations may be required to track withdrawal

volumes, evaporation losses, reinjection rates and water quality parameters across

multiple monitoring points. Emerging DLE technologies add new streams, reagents

and waste forms that must also be measured and reported for ESG disclosure

frameworks such as GRI, SASB and TCFD.

Generic asset management setups sometimes lack data models

and workflows to capture these environmental metrics in a structured, auditable

way linked to assets and work activities.

This gap forces operators into a parallel ecosystem of

spreadsheets and standalone tools, making it harder to demonstrate compliance,

respond to regulator queries, or provide consistent ESG narratives to

investors.

3.0 Operational Realities

That Drive Failures.

Understanding the physical realities of lithium extraction

helps clarify why generic maintenance strategies tend not to perform very well

and what ‘good’ needs to look like.

3.1 Brine Evaporation:

Chemistry Driven Degradation.

High‑salinity brines used for lithium recovery often contain

complex mixtures of sodium, calcium, magnesium and other ions that promote

scaling on evaporative and heat transfer surfaces.

As brine evaporates, concentration factors increase and

scaling risks rise, which can choke flow paths, reduce heat transfer efficiency

and foul sensors and level instrumentation.

Pumps, pipelines and valves in these systems also face

corrosive attack that can rapidly degrade seals, impellers and metallic

internals.

Effective maintenance in this context requires strategies

that explicitly integrate chemistry‑based monitoring, scaling indices and variable

inspection intervals driven by concentration and temperature rather than fixed

calendar cycles.

Asset management setups should therefore support attributes

such as brine composition, operating temperature ranges and scaling risk

indicators at the asset level, with workflows that trigger cleaning,

inspection, or material changes when thresholds are crossed.

3.2 Hard Rock Spodumene:

Abrasive, Hardness‑Driven Wear.

Hard‑rock lithium mining from spodumene involves multi‑stage

crushing, grinding and beneficiation of a moderately hard and abrasive ore.

The ore’s mechanical properties, including hardness and

abrasion index, strongly influence crusher liner wear, mill energy consumption

and media usage.

Calcination stages used to convert spodumene to more reactive

phases introduce additional thermal stresses and equipment demands.

These realities mean that maintenance strategies should be

closely tied to ore characteristics and process parameters, not just equipment

running hours.

Asset management setups that capture ore type, hardness data

and throughput alongside component condition and failure histories can support

adaptive scheduling, such as shortening liner change intervals when

particularly hard campaigns are processed.

Generic PM libraries that ignore these linkages tend to

either mis‑time critical interventions or drive unnecessary maintenance during

softer runs.

3.3 Remote Locations And

Fragile Infrastructure.

Many lithium resources are found in deserts, high plateaus,

or sparsely populated regions where road, power and telecom infrastructure are

limited.

Seasonal access constraints, long supply routes and

constrained local service capability increase the cost of unplanned failures

and lengthen repair times.

At the same time, intermittent connectivity undermines real‑time

access to cloud‑hosted CMMS, EAM or ERP platforms, especially for mobile workers.

An effective system design in this context prioritises

offline‑capable mobile apps, store‑and‑forward synchronisation and local

caching of critical asset and work data. It also incorporates supply chain

integration that reflects long lead times and the need for strategic spares,

particularly for specialised equipment exposed to high wear or corrosion.

Generic asset management setups that assume short lead times

and constant connectivity tend to generate unrealistic PM’s and unreliable historic

data.

3.4 Regulatory And ESG

Intensification.

Regulators and stakeholders increasingly expect lithium

operators to provide transparent, auditable data on water use, emissions and

ecosystem impacts.

Water balance reporting for DLE and evaporation ponds may

require quantifying withdrawals, consumptive use, recycling rates and discharge

qualities at a high temporal resolution.

ESG frameworks also drive the need for consistent metrics on

energy intensity, greenhouse gas emissions and land disturbance.

Aligning CMMS/EAM/ERP asset managment structures with these

requirements means treating environmental monitoring points, sampling campaigns

and key process parameters as managed assets with defined inspection

frequencies, calibration tasks and data capture workflows.

When environmental data remains disconnected from asset and

maintenance records, it is harder to demonstrate that equipment condition,

process control and compliance are being managed in a coherent way.

4.0 Strategic Implications

For Leaders.

For leaders in the maintenance, operations and engineering

departments, the key implication is that ‘generic’ is itself a risk category in

lithium environments.

4.1 Maintenance And Reliability

Leadership.

Maintenance managers need to ensure that maintenance strategies

and master data configurations are explicitly linked to lithium‑specific

degradation mechanisms and this could mean:

1. Grounding preventive

and predictive programs in chemistry, geology and process conditions, not just standard

reliability engineering data tables.

2. Capturing relevant

variables in asset records, including brine chemistry ranges, ore hardness

bands, key process temperatures and scaling indices.

3. Building inspection

and condition‑based tasks that trigger on changes in those variables, such as

increased scaling risk or shifts in ore feed hardness.

Without these structures, teams are limited to time‑based

maintenance and retrospective analysis, which tends to produce higher reactive

work and weaker equipment availability.

4.2 Operations And Production

Leadership.

Operations leaders carry the production risk associated with

system misalignment. In brine operations, failures in pumping, evaporation, or

reinjection systems can disrupt water balances and evaporation cycles, leading

to prolonged recovery times.

In hard‑rock circuits, unexpected failures of crushers,

mills, or classification equipment can rapidly reduce output and drive costly

overtime or emergency maintenance.

To manage these risks, operations leaders should insist on:

1. Maintenance

Strategies that reflect realistic equipment life under current chemistry and

ore conditions.

2. Integrated materials

management that recognises long lead times and ensures critical & insurance

spares are held for high‑risk assets.

3. Feedback loops where

production changes (new ore sources, process adjustments) are quickly reflected

in maintenance strategies and system configuration.

4.3 CIOs And Technology

Strategy.

Technology leaders must design architectures that are robust

to connectivity constraints and aligned with data governance requirements for

both operations and ESG. Priority areas typically include:

1. Offline‑first mobile

execution, with secure, reliable synchronisation to central CMMS/EAM/ERP

platforms.

2. Data models that link

asset performance, maintenance events, environmental monitoring and ESG metrics

in a consistent, auditable way.

3. Integration with IoT

sensors and process historians where appropriate, so that key condition

indicators can drive automated triggers or analytics without excessive manual

entry.

Cybersecurity and access control also become more important

as remote monitoring, cloud hosting and third‑party analytics platforms are

introduced into the mining ecosystem.

4.4 Organisational Readiness

And Change.

Even the best‑configured system will fail if people,

processes and governance do not align with lithium‑specific realities. Leaders

should consider:

1. Role‑based training

that explicitly links asset care practices to the chemistry and geology of

lithium operations.

2. Governance structures

that keep master data, PM libraries and environmental metrics under disciplined

control.

3. Continuous improvement

cycles where lessons from failures, inspections and ESG reporting feed back

into CMMS configuration and strategy.

This emphasis on organisational readiness is often the

decisive factor that differentiates operations that extract value from tailored

configurations from those that fall back into reactive habits.

5.0 Enabling Technology

For Process Linked Maintenance Strategies.

Achieving the linkage between lithium‑specific degradation

mechanisms and CMMS/EAM strategies requires an integrated operations technology

stack, where real‑time process data from historians and DCS flows into asset

systems via standard interfaces.

This setup leverages established tools like Process Historian

(AVEVA PI System), Yokogawa DCS (CENTUM VP), and Operations Management Systems

(OMS), connected to CMMS/EAM (e.g., IBM Maximo, Infor EAM) and ERP (e.g., SAP

S/4HANA) through APIs, middleware, and data connectors.

5.1 Core Technology Components.

5.1.1 Process Historian (AVEVA PI

System).

This captures high‑frequency time‑series data from plant

instruments, such as brine TDS, temperature, pH, ore hardness proxies (e.g.,

power draw) and flow rates. PI Asset Framework (AF) models assets

hierarchically and enriches tags with context like “Pump‑P101: Scaling Risk = f(TDS, Temp)”, making data

contextual and queryable.

Just

to explain, AVEVA PI System is a

complete data management platform where the historian functionality

is provided by its core PI Data Archive component.

Quick Structure Breakdown.

AVEVA PI System = Suite of Tools

├── PI Data Archive (the actual

*historian* database – stores time-series data)

├── PI Asset Framework (AF)

(models assets, calculates derived values like Scaling Risk)

├── PI Connectors/Interfaces

(collect data from DCS/PLC)

├── PI Integrator (pushes data to

EAM/ERP)

└── PI Vision/ProcessBook

(dashboards)

When I mention ‘Process

Historian (AVEVA PI System)’, I’m referring to:

1.

PI Data Archive as the time-series storage engine (the literal

historian)

2.

Plus PI AF for asset context (brine chemistry → pump degradation models)

3.

Plus connectors that feed it from Yokogawa DCS

In practice: Your DCS streams brine TDS data → PI Data Archive stores it → PI AF calculates “Scaling Risk Score” → PI Integrator sends score to Maximo to trigger pump

inspection.

The PI System is the

full ecosystem; Data Archive is the historian heart. Both get casually

called “PI” in industry conversation.

5.1.2 Distributed

Control System (DCS, e.g., Yokogawa CENTUM VP).

This manages real‑time

control loops, alarms and HMI visualization for brine evaporation, crushing circuits, or flotation cells.

It exposes process

variables via OPC UA/DA or proprietary protocols for upstream archiving.

Yokogawa

CENTUM VP is Yokogawa’s flagship Distributed Control System (DCS), it’s a

robust, scalable platform for real-time process automation and control in

industries like mining, chemicals, and oil & gas.

Core Purpose.

A DCS like CENTUM VP

acts as the ‘central nervous system’ of a processing

plant, managing thousands of control loops (e.g., brine pumps, crusher speeds,

flotation pH) across distributed controllers rather than a single centralized

computer.

It continuously reads

sensors, executes control logic, adjusts valves/actuators, and presents

operator interfaces, all with 99.99999%

availability via redundant ‘pair & spare’ architecture.

Key Components &

Structure.

CENTUM VP DCS = Complete Control Platform.├──Field Control Stations (FCS): Distributed controllers (redundant CPUs) executing process logic

├──Human Interface Stations (HIS): Operator HMI screens for monitoring/control

├──Vnet/IP Network: 1Gbps redundant backbone (fiber/UTP) connecting everything

├──N-IO/FIO Modules: Universal I/O (AI/AO/DI/DO) with built-in signal conditioning

├──Engineering Workstation: Logic configuration & database management

└──Unified Gateway Station (UGS): Interfaces to Modbus, Ethernet/IP, Profibus, etc.

Lithium Mining Context.

1.

Brine

evaporation: Controls pond levels,

pump speeds, chemical dosing based on TDS/chemistry loops streamed to AVEVA PI

historian.

2.

Hard-rock

processing: Manages crusher load,

mill power draw, flotation reagent addition with real-time alarming & trending.

3.

Remote

deployment: FCS controllers can be

field-mounted (Zone 2 hazardous areas) with N-IO baseplates handling intrinsic

safety.

Data Flow To

Historian/CMMS.

Sensors→N-IO→FCS Controller→Vnet/IP→AVEVA PI Data Archive

↓

Operator HIS (alarms, trends)↓

OPC UA→PI Integrator→Maximo EAM (triggers)

Key

Integration Points:

1.

OPC UA/DA: Exposes 10,000+ live process tags (brine TDS, crusher

amps) to historians.

2.

Fieldbus

Support: FOUNDATION Fieldbus,

Profibus-DP for smart instruments.

3.

Pair

& Spare Redundancy: Dual CPUs compare

outputs continuously; <1ms failover.

Example Operator View.

HIS screen shows:

Pump P-101: Speed 75%, TDS 210k ppm↑, Scaling Alert Active

↓Auto-generate WO in Maximo via PI threshold breach

CENTUM VP has evolved

since 1975, with R7 (2025) adding AI operator assistance, Windows 11 support,

and virtualization to reduce server footprints.

In lithium plants, it

delivers the real-time process

backbone that feeds degradation data into historians for

maintenance intelligence.

5.1.3 Operations

Management System (OMS).

This

Sits above DCS/historian to aggregate data into KPIs,

trends, and operator workflows (often part of DCS or historian suites like

AVEVA Operations Center). In lithium contexts, OMS dashboards might display

brine chemistry trends or crusher wear indicators for operator awareness.

5.2 OMS Setup For Lithium

Operations.

The OMS needs to be configured with asset hierarchies

and calculated tags that reflect lithium‑specific drivers:

1. Brine evaporation: OMS calculates

scaling propensity indices (e.g., Langelier Saturation Index) from DCS inputs

like conductivity, temperature, and ion proxies, alerting on thresholds that

correlate with fouling.

2. Hard‑rock processing: Tracks cumulative

“abrasive ton‑hours” or hardness‑adjusted wear rates by combining throughput,

power consumption, and periodic lab assays.

3. Remote resilience: Edge processing and

local buffering ensure data availability during connectivity gaps, with secure

sync to central OMS.

This creates a unified view of process health that

maintenance can reference without manual reconciliation.

This sub section refers to configuring a high-level operational oversight

platform (like AVEVA Operations Center, Yokogawa Exaquantum, or DCS-integrated

dashboards) to aggregate, contextualize and visualize process data specifically

for lithium extraction challenges.

Core Purpose.

OMS sits above DCS and historian as an operations intelligence layer,

turning raw tags (TDS, crusher power) into actionable KPIs, alerts, and trends

for shift operators and supervisors.

In lithium plants, it

bridges real-time control with maintenance foresight by calculating degradation proxies from process

signals.

Key Lithium-Specific

Configurations.

OMS Hierarchy for Lithium Plant├──Area: Brine Evaporation Ponds

│├──KPI: Scaling Risk Index = f(TDS, Temp, pH) > Threshold→Alert

│├──Pond P-101: Level, Evap Rate, Chemistry Trends

│└──Pump Fleet: Cumulative Runtime @ High Salinity

├──Area: Hard-Rock Processing

│├──KPI: Abrasive Wear Rate = f(Power Draw, Throughput, Ore Proxy)

│├──Crusher C-001: Liner Life Remaining (%), Ore Hardness Trend

│└──Mill Circuit: Grind Efficiency vs. Media Wear

└──Site-Wide: Water Balance, Energy Intensity, Remote Sync Status

Setup Steps.

1. Calculated Tags for Degradation

Proxies.

Brine Scaling Alert:IF (TDS > 200k ppm AND Temp > 55°C for 24h) THEN Scaling_Index = (Ca_hardness * Mg_ratio * Temp_factor)OMS displays: "PUMP INSPECTION DUE"→DCS alarm→PI event→EAM WO

Crusher Wear Proxy:Abrasion_Hours = Throughput_tph * Power_kW * Hardness_Factor (lab assay avg)When Abrasion_Hours > Liner_Threshold→"LINER CHANGE SOON" dashboard

2. Lithium-Relevant Dashboards.

Operator

Shift Handover Screen:

ACTIVE ALERTS: Brine Pump P-103 (Scaling Risk: HIGH)

TRENDS: Crusher C-002 power spiked +18% (hard ore campaign)

WATER BALANCE: Pond fill 82%, evap loss 1.2ML/day OK

MAINTENANCE: 2x pump WOs auto-generated via PI Integrator

3. Remote Lithium Site Resilience.

1.

Edge

Computing: Local OMS server caches

72hrs data during satcom outage.

2.

Prioritized

Sync: Critical KPIs (scaling risk, wear

rates) sync first when reconnected.

3.

Mobile

Access: Supervisors view KPIs

via tablet (4G/satcom) 50km from site.

4. Integration Points.

DCS (Yokogawa CENTUM VP)→Historian (PI Data Archive)→OMS

↓Raw Tags (1000s)↓Compressed (100s)↓KPIs/Alerts (10s)

Brine TDS 210k ppm Scaling_Index = 1.8 "INSPECT PUMPS"Example Operator Workflow.

08:15: OMS dashboard flashes "CRUSHER LINER RISK: 92% consumed"08:16: Operator checks trend: Ore hardness +22% vs baseline08:17: OMS auto-emails planner: "C-001 liner change recommended by EOD"08:18: DCS adjusts crusher speed -5% to extend life08:30: Maintenance WO appears in Maximo with embedded OMS trend chartVendor Examples in Lithium

Context.

1.

AVEVA

Operations Center: Plant-wide KPI

rollups, role-based views (operator vs. manager)

2.

Yokogawa

Exaquantum: DCS-native, integrates

CENTUM VP alarms with PI historian

3.

AspenTech

APM: Process-focused, strong on

calculated degradation indices

Outcome.

Operators see “Pump scaling risk: HIGH”

instead of raw TDS=210kppm. Maintenance gets preemptive work orders with context.

Executives track fleet-wide wear trends across

brine/hard-rock assets.

The OMS becomes the single pane of glass where process

meets maintenance.

This setup transforms

generic process data into lithium-specific

operational intelligence without custom coding—just deliberate

tag math and hierarchy design.

5.3 Integration Architecture

To CMMS/EAM/ERP.

Data flows from OMS to enterprise systems via bidirectional

interfaces, enabling context‑aware maintenance:

|

Layer |

Technology |

Data Flow Example |

Protocol/Method |

|

Process |

DCS

(Yokogawa) →

Historian (AVEVA PI) |

Real‑time

brine TDS, crusher power draw |

OPC

UA, PI Connectors |

|

Operations |

OMS

(AVEVA Operations Center) |

Aggregated

KPIs (e.g., Scaling Risk Score) |

PI

AF Events, PI Notifications |

|

Asset |

CMMS/EAM

(Maximo/Infor) |

Auto‑populate

asset attributes; trigger PMs (e.g., inspect when Scaling Score > 1.5) |

PI

Integrator for EAM, REST APIs, PI Web API |

|

Enterprise |

ERP

(SAP) |

Parts

forecasting from wear rates; compliance reports |

ERP

Connectors (e.g., PI to SAP IDoc), Kafka/MQ |

1. Historian to EAM: AVEVA PI Integrator

pushes enriched tags (e.g., “Ore Hardness Avg”) as meter readings or work

triggers into EAM, updating asset contexts dynamically.

2. OMS to CMMS: Event notifications

(e.g., “High Corrosion Threshold Breached”) auto‑generate work orders or adjust

PM intervals.

3. EAM to ERP: Maintenance events

and failure modes feed back for spares planning and cost allocation, closing

the loop.

Middleware like OSIsoft PI Integrator, Kepware, or Azure IoT

Hub handles protocol translation and data normalization for remote sites.

5.4 What Might An Integrated

System Looks Like?

1. Planner’s view (EAM): Work order for

brine pump shows linked PI trends: ‘TDS spiked to 250k ppm last cycle, recommend

seal inspection’ with embedded charts.

2. Operator’s view

(OMS/DCS):

Dashboard flags ‘Crusher Liner Risk: High (Ore Hardness +15% vs. baseline)’,

prompting feed adjustments before maintenance handover.

3. Executive view (ERP): Reports forecast ‘$X

increased spares due to abrasive campaign’, tied to process data for capex

justification.

This architecture seems to be well supported in this current

era of in mining (e.g., Barrick Goldstrike uses AVEVA PI for compliance and

performance).

It shifts maintenance from reactive calendars to process‑aware

intelligence without requiring custom development—just disciplined integration.

6.0 Terms And

Abbreviations Used.

This section defines key technical terms and abbreviations

used throughout the article, incorporating detailed explanations of core

operational technology components relevant to lithium mining asset management.

6.1 Key Terms.

1. Asset Framework (AF): Modeling layer in

AVEVA PI System that organizes time-series data into equipment hierarchies with

calculated attributes (e.g., “Scaling Risk Index” derived from brine

TDS and temperature).

2. AVEVA PI System: Comprehensive data

management platform where PI Data Archive serves as the core time-series

historian database, PI Asset Framework (AF) adds asset context, and PI

Integrator pushes data to EAM/ERP systems.

3. Bill of Materials

(BOM):

Structured list of spare parts and components linked to assets in CMMS/EAM for

repair planning and inventory management.

4. Brine Evaporation: Lithium extraction

process where saline groundwater is concentrated in solar ponds, creating

extreme scaling and corrosion conditions for pumps and pipelines.

5. CENTUM VP: Yokogawa’s

distributed control system (DCS) featuring Field Control Stations (FCS), Human

Interface Stations (HIS), Vnet/IP network, and N-IO universal I/O modules for

real-time process control.

6. Condition-Based

Maintenance (CBM): Maintenance triggered by real-time equipment condition

data (e.g., scaling risk thresholds) rather than fixed calendar intervals.

7. Distributed Control

System (DCS): Plant automation backbone (e.g., Yokogawa CENTUM VP)

managing thousands of control loops across redundant controllers with operator

HMI interfaces.

8. Degradation

Mechanisms:

Equipment wear processes unique to lithium operations, including brine-induced

corrosion/scaling and spodumene ore abrasiveness.

9. Enterprise Asset

Management (EAM): Advanced CMMS platforms (e.g., IBM Maximo, Infor EAM)

supporting reliability analytics, condition-based strategies, and whole-life

asset optimization.

10. Enterprise Resource Planning

(ERP):

Business platform (e.g., SAP S/4HANA) integrating finance, procurement, and

supply chain with EAM data flows.

11. Failure Modes and

Effects Analysis (FMEA): Risk assessment methodology identifying equipment failure

causes and mitigation strategies to inform PM libraries.

12. Field Control Station

(FCS):

Distributed controller in CENTUM VP executing process control logic with

pair-and-spare redundancy.

13. Human-Machine

Interface (HMI): Operator workstations (HIS in CENTUM VP) displaying

process trends, alarms, and control functions.

14. Master Data: Foundational

CMMS/EAM information including asset hierarchies, task templates, custom

attributes (e.g., “Ore Hardness”), and BOMs.

15. N-IO: Yokogawa’s

universal I/O system with built-in signal conditioning for field instruments in

hazardous areas.

16. Operations Management

System (OMS): Intelligence layer (e.g., AVEVA Operations Center,

Yokogawa Exaquantum) aggregating DCS/historian data into lithium-specific KPIs

like scaling risk and wear rates.

17. PI Data Archive: Core time-series

database component of AVEVA PI System storing compressed process data (tags)

with timestamps and quality flags.

18. Process Historian: High-frequency

time-series database optimized for industrial sensor data (e.g., AVEVA PI Data

Archive, Aspen IP.21).

19. Reliability Centered

Maintenance (RCM): Structured methodology defining maintenance strategies

based on failure consequences and detection methods.

20. Spodumene: Lithium-bearing

hard-rock mineral requiring crushing, grinding, and calcination, creating

variable abrasive wear patterns.

21. Vnet/IP: Yokogawa’s 1Gbps

redundant industrial network backbone connecting DCS components.

6.2 Abbreviations.

|

Abbreviation |

Full Form |

Description |

|

AF |

Asset

Framework |

PI

System asset modeling layer |

|

BOM |

Bill

of Materials |

Asset

component inventory |

|

CBM |

Condition-Based

Maintenance |

Real-time

condition triggered work |

|

CMMS |

Computerized

Maintenance Management System |

Work

order and scheduling software |

|

DCS |

Distributed

Control System |

Real-time

plant control platform (CENTUM VP) |

|

EAM |

Enterprise

Asset Management |

Advanced

asset lifecycle management |

|

ERP |

Enterprise

Resource Planning |

Enterprise

business integration |

|

ESG |

Environmental,

Social & Governance |

Sustainability

reporting framework |

|

FCS |

Field

Control Station |

CENTUM

VP process controller |

|

FMEA |

Failure

Modes and Effects Analysis |

Equipment

failure risk analysis |

|

HMI |

Human-Machine

Interface |

Operator

control screens |

|

HIS |

Human

Interface Station |

CENTUM

VP operator workstation |

|

OMS |

Operations

Management System |

Process

KPI aggregation layer |

|

PI |

PI

System (AVEVA) |

Industrial

data infrastructure |

|

PM |

Preventive

Maintenance |

Scheduled

reliability tasks |

|

RCM |

Reliability

Centered Maintenance |

Risk-based

strategy design |

|

TDS |

Total

Dissolved Solids |

Brine

salinity measure (ppm) |

|

UGS |

Unified

Gateway Station |

CENTUM

VP external protocol interface |

7.0 Conclusion.

Lithium extraction environments do not

necessarily require new CMMS, EAM, or ERP technologies, but they do benefit

from deliberate integration of proven operational systems that address the

shortcomings of generic, template driven strategies.

Brine operations and hard‑rock spodumene circuits create

corrosion, scaling and abrasive wear patterns that DCS platforms such as Yokogawa CENTUM

VP capture in real time.

Process historians like AVEVA PI System

archive and contextualise these signals, and Operations Management Systems

convert them into maintenance intelligence that reflects actual operating

conditions.

Remote lithium sites with fragile

connectivity require offline first EAM configurations supported by process

aware data flows rather than calendar based assumptions.

Increasing ESG scrutiny demands auditable

environmental metrics linked directly to asset performance records, not

isolated spreadsheets or manual reporting.

Organizations that persist with

disconnected, generic maintenance strategies and overall asset management

setups face ongoing reactive maintenance, unreliable degradation forecasting

and fragmented compliance reporting.

Those that do the clever work (although

this comes at a cost) and integrate their DCS, historian, OMS, EAM and ERP systems

around lithium specific realities such as brine chemistry thresholds, ore

hardness variability and water balances achieve predictive maintenance

capability, resilient remote execution, and defensible sustainability metrics.

The technology required to support this already exists

across all major vendors. Success belongs to operations that configure it with

discipline, linking process reality to asset strategy across the full lifecycle

of their lithium infrastructure.