Continuous Improvement

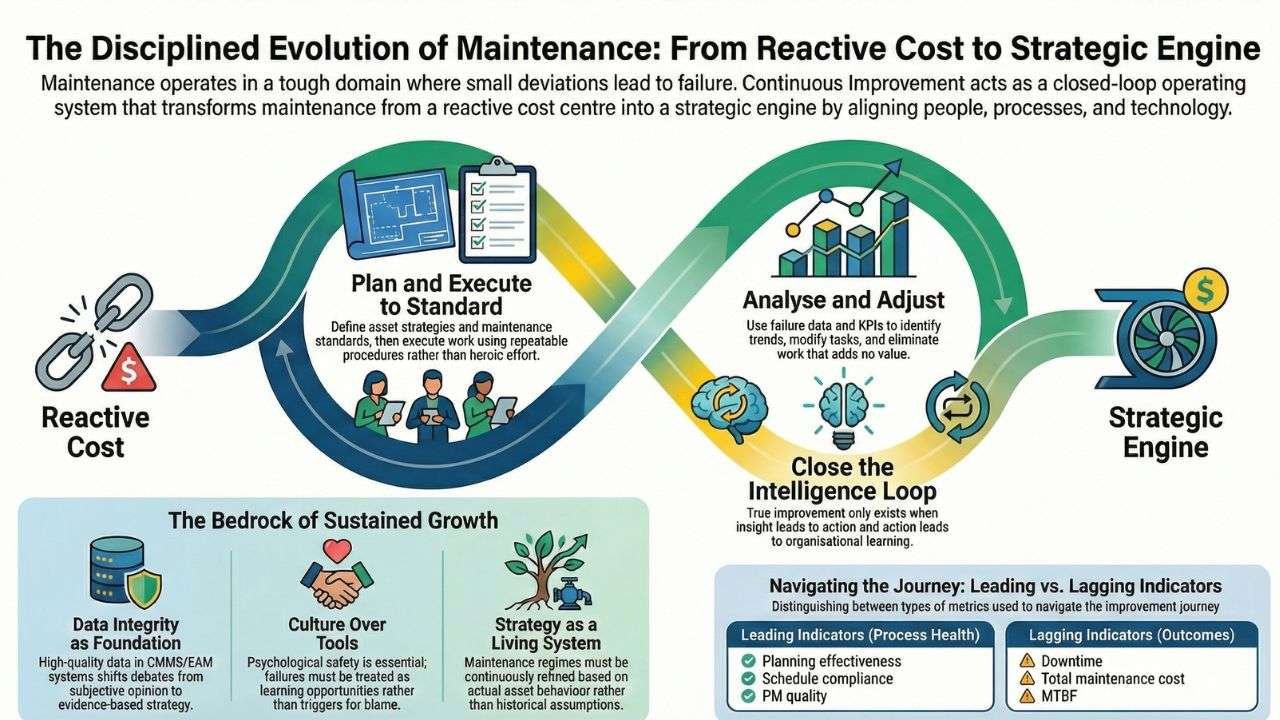

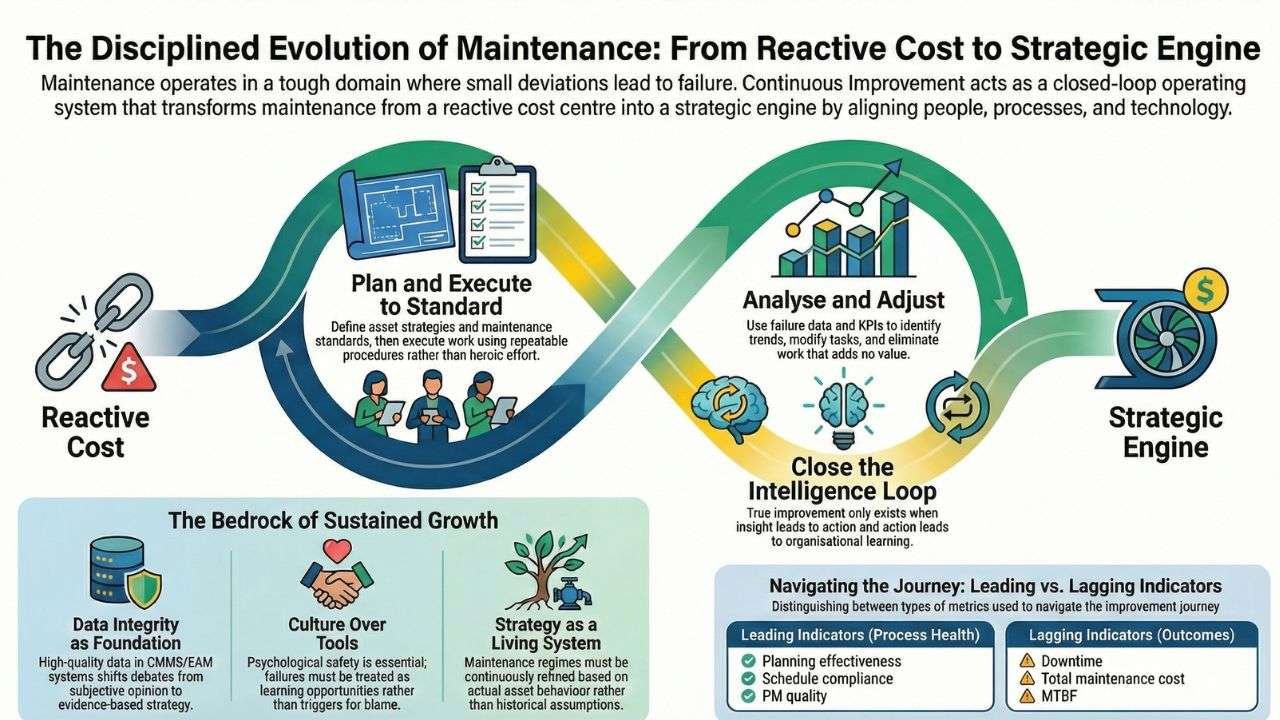

Continuous Improvement is often described as a universal good, something organisations should pursue because it “sounds right.”

In maintenance and asset management, it is far more than that. It’s a non‑negotiable requirement for sustaining reliability, controlling risk and protecting long‑term asset value.

Assets age, operating conditions shift, failure modes evolve and business expectations intensify. In this environment, standing still is not neutral; it is a form of regression.

Within maintenance departments, Continuous Improvement is the disciplined pursuit of better outcomes through learning, feedback and refinement.

It is not a Lean toolkit, a cost‑cutting initiative or a periodic burst of enthusiasm. It is an operating philosophy that shapes how work is planned, executed, analysed and improved.

When embedded properly, it transforms maintenance from a reactive cost centre into a strategic engine of organisational performance.

What Continuous Improvement Means In A Maintenance Context.

At its core, Continuous Improvement is the structured, ongoing effort to enhance processes, systems and outcomes through incremental learning and deliberate change.

In maintenance, this means continually improving asset availability, reliability, safety, cost efficiency and lifecycle value, not through heroic effort, but through repeatable systems.

Unlike project‑based improvement programs, Continuous Improvement has no endpoint. It operates through closed feedback loops: plan work based on current knowledge, execute tasks to standard, measure results, analyse deviations and adjust strategies.

Over time, this cycle builds organisational intelligence. Decisions become evidence‑based rather than assumption‑driven and improvement becomes embedded rather than episodic.

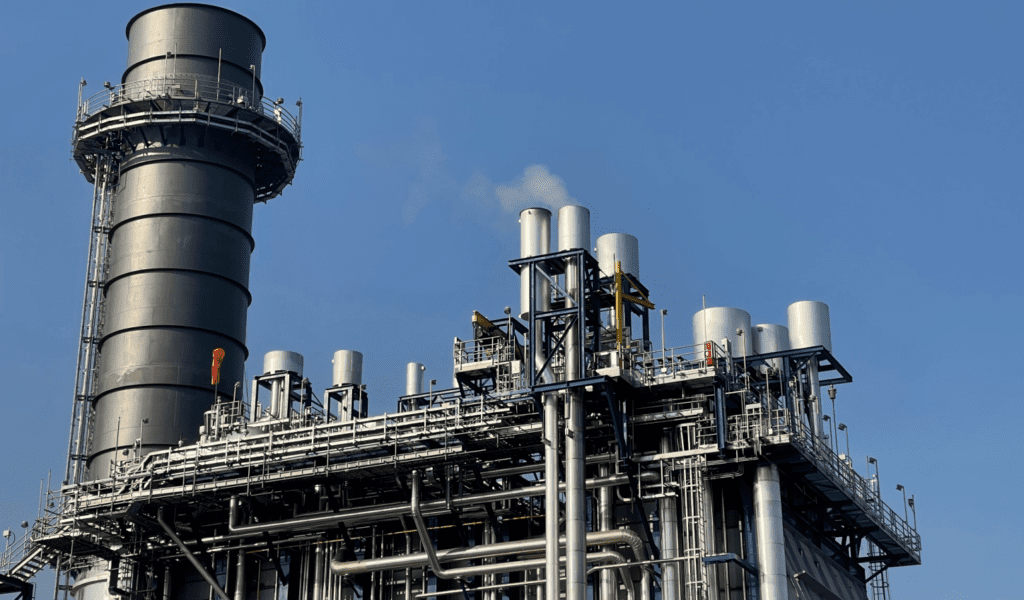

Why Continuous Improvement Is Essential To Maintenance.

Maintenance operates in a tough and often unforgiving domain.

Failures sometimes remain invisible until they become catastrophic.

Small deviations in lubrication, alignment, inspection quality or operating conditions can compound silently for months or years before manifesting as downtime, safety incidents or premature asset replacement.

In such an environment, reactive approaches are not merely inefficient, they are dangerous.

Continuous Improvement functions as a risk‑mitigation mechanism.

It enables organisations to detect weak signals early, refine preventive strategies, optimise task frequencies, eliminate non‑value‑adding work and focus effort where risk and consequence are highest.

Financially, the impact is equally significant. Maintenance costs are shaped less by labour and spares than by the quality of upstream decisions: how assets are maintained, how failures are prevented and how data informs strategy.

Continuous Improvement ensures these decisions evolve alongside asset behaviour rather than remaining frozen in time.

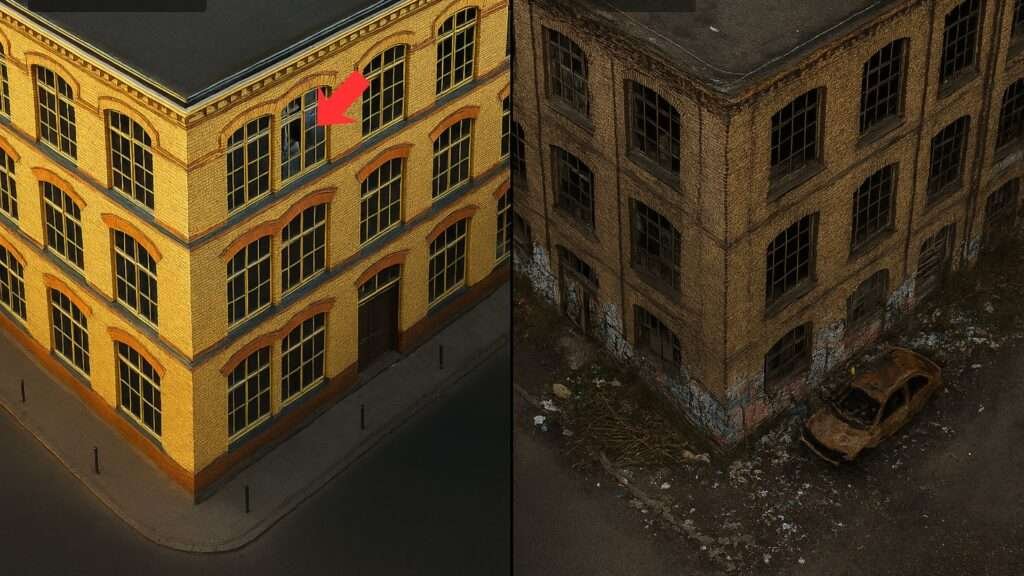

Maintenance Maturity And The Improvement Journey.

Maintenance organisations typically progress through recognisable maturity stages: reactive, preventive, predictive, reliability‑centred and ultimately optimised.

Continuous Improvement exists at every stage, but its effectiveness depends on how structured and intentional it is.

At lower maturity levels, improvement is informal and personality‑driven, reliant on experience, intuition or isolated problem‑solving.

As maturity increases, improvement becomes systematic. Work is planned rather than chased. Failures are analysed rather than accepted. Strategies are reviewed rather than assumed to be correct.

Crucially, maintenance maturity and system maturity must evolve together.

A sophisticated asset management system cannot compensate for poor discipline or unclear processes. Likewise, a strong improvement culture will eventually outgrow inadequate tools.

Continuous Improvement acts as the bridge, aligning people, processes and systems into a coherent whole.

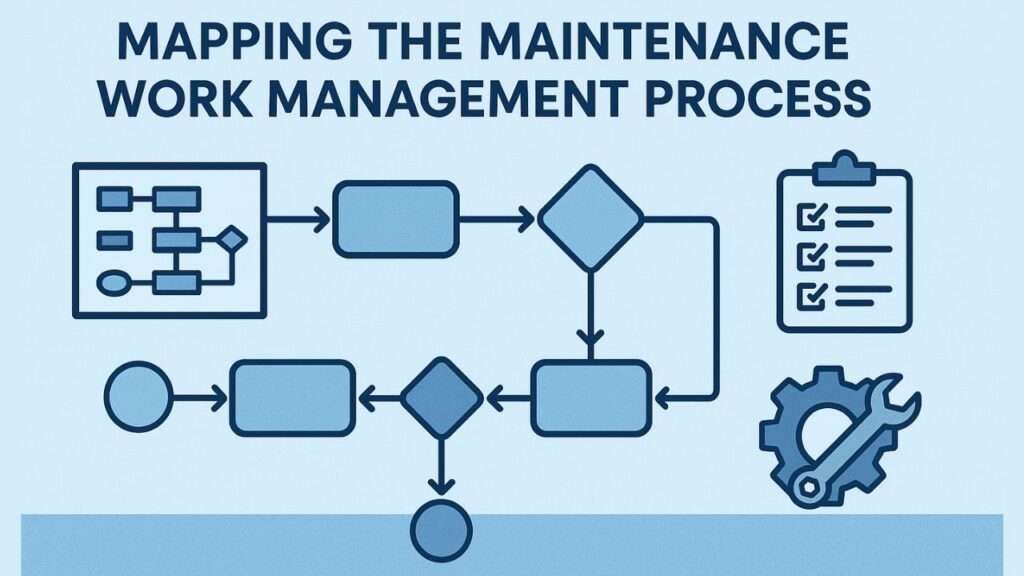

Continuous Improvement As A Closed‑Loop System.

Effective Continuous Improvement in maintenance operates as a closed loop, not a linear process.

It begins with clear planning: defining asset strategies, maintenance standards and performance expectations.

Work is executed using standard job plans, schedules and procedures. Measurement follows execution, using KPIs, work order data, failure information and compliance metrics to reveal how assets and processes are performing.

Analysis converts this data into insight, identifying trends, recurring issues and improvement opportunities.

Improvement actions follow: modifying tasks, updating job plans, adjusting intervals or addressing systemic causes.

Successful changes are then standardised and governed to ensure gains are sustained.

Where organisations fail is not in collecting data, but in closing the loop. Continuous Improvement only exists when insight leads to action and action leads to learning.

Culture, Behaviour And The Human Dimension.

Systems and processes matter, but Continuous Improvement ultimately depends on people. Technicians, planners and supervisors are the primary generators of information and the custodians of asset knowledge. Their engagement determines data quality, compliance and the credibility of analysis.

A culture that supports Continuous Improvement encourages transparency rather than blame.

Failures are investigated to understand causes, not assign fault. Deviations from plan are treated as learning opportunities, not disciplinary triggers.

Psychological safety is essential for surfacing the truth about asset condition and work effectiveness.

Leadership is decisive. What leaders ask, measure and reward shapes behaviour. If speed is prioritised over quality, data will suffer.

If compliance is emphasised without context, improvement will stagnate. Continuous Improvement thrives when leadership reinforces learning, discipline and long‑term thinking.

Maintenance Strategy As A Living System.

One of the most powerful applications of Continuous Improvement is in maintenance strategy itself.

Preventive maintenance programs, inspection regimes and task frequencies should not be static artefacts created once and forgotten.

They should be living systems, continuously refined based on performance outcomes and failure behaviour.

Through structured analysis, trend reviews, root cause investigations, cost‑risk assessments, organisations can determine whether existing strategies are effective or require adjustment.

Tasks that do not prevent failure can be modified or eliminated. Emerging risks can be addressed proactively.

This adaptive approach ensures maintenance effort remains aligned with asset reality rather than historical assumptions.

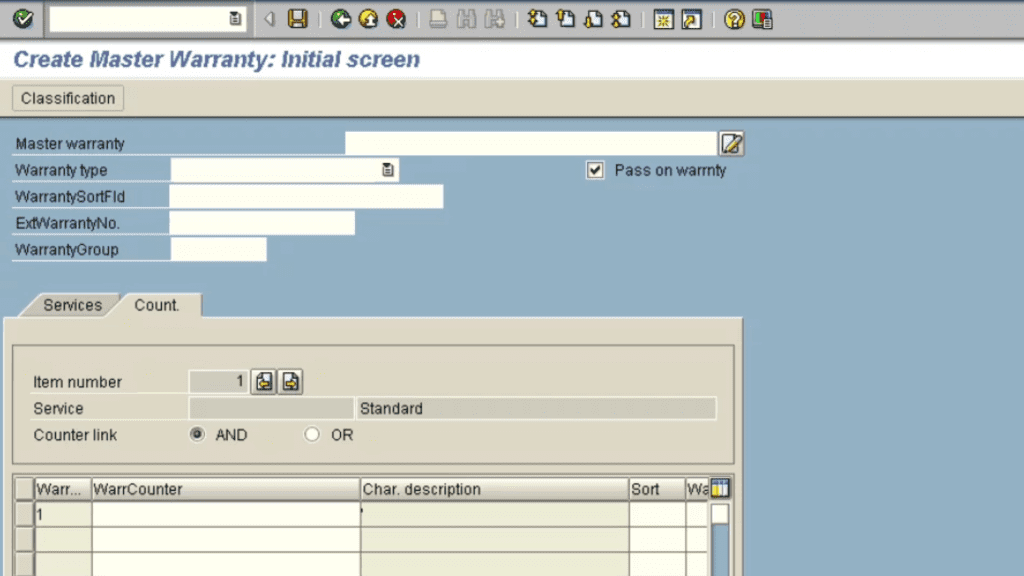

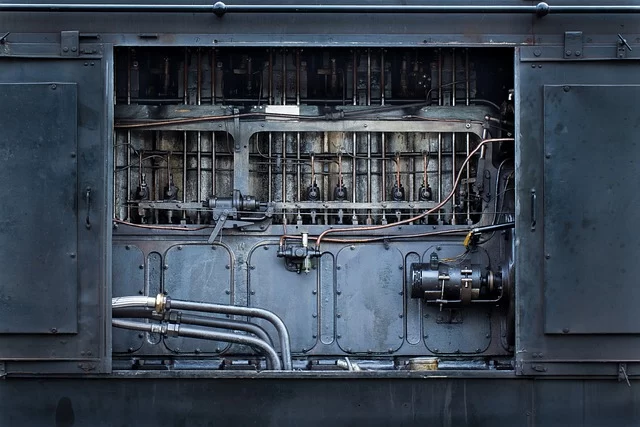

The Role of CMMS, EAM And ERP Systems.

CMMS, EAM and ERP platforms are central enablers of Continuous Improvement, but only when used intentionally.

These systems are not administrative burdens or work order repositories; they are the institutional memory of the maintenance organisation.

At a foundational level, they provide structure: asset hierarchies, workflows, scheduling and history.

At higher maturity, they enable insight: trend analysis, failure mode visibility, performance tracking and strategy validation.

Ultimately, they support governance by standardising processes and preserving learning beyond individual experience.

Technology alone does not create improvement. Poor configuration, inconsistent data entry and weak analytical discipline can render even the most advanced system ineffective. Continuous Improvement depends not on having a system, but on using it as a learning engine.

Data Integrity: The Bedrock Of Improvement.

Data quality is the silent determinant of Continuous Improvement success. Inaccurate failure codes, incomplete work orders, inconsistent asset structures and vague descriptions undermine analysis and lead to false conclusions.

Reliable improvement depends on the ability to see patterns over time, what fails, how often, why and at what cost.

This requires discipline at the point of data entry and clear standards for how information is captured and used. Data integrity is not a clerical issue; it is a leadership and governance responsibility.

When data quality is high, improvement priorities become obvious, resources are better targeted and debates shift from opinion to evidence.

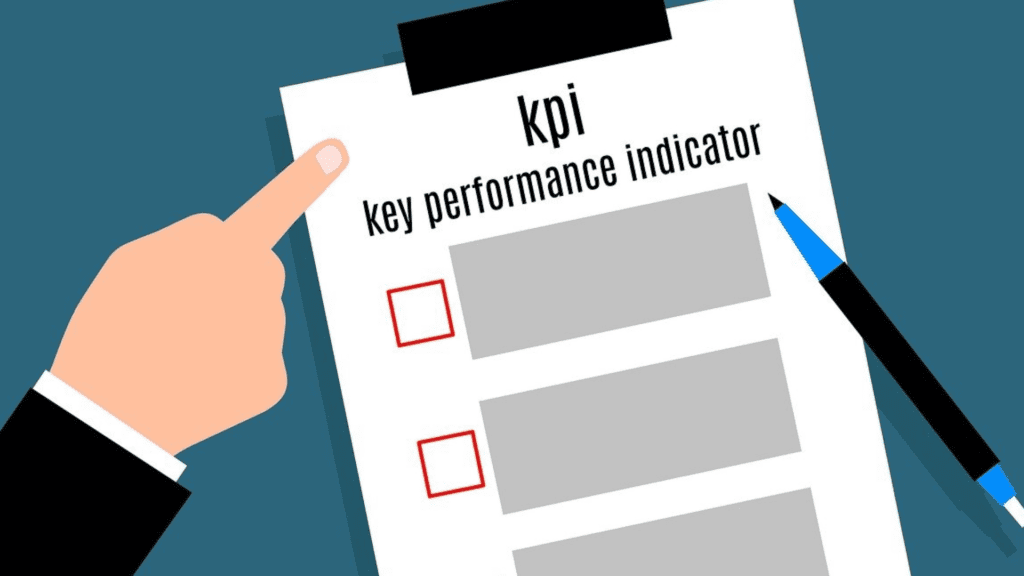

Measuring What Matters.

Continuous Improvement requires meaningful measurement, not excessive measurement. The goal is not to track everything, but to monitor indicators that guide learning and action.

Lagging indicators, downtime, cost, MTBF, reveal outcomes.

Leading indicators, planning effectiveness, schedule compliance, backlog health, PM quality, reveal process health.

Effective organisations use metrics to ask better questions. When indicators deteriorate, the focus shifts to understanding why and what can be improved. Metrics become navigational tools rather than scorecards.

As maturity increases, measurement systems must evolve. What matters in a reactive environment differs from what matters in an optimised one.

Governance, Standards And Sustaining Gains.

Without governance, Continuous Improvement becomes fragmented and inconsistent. Changes to strategies, job plans and system configurations must be controlled, reviewed and documented. This ensures improvements are deliberate, repeatable and auditable.

Standardisation does not inhibit improvement; it enables it. Clear baselines allow organisations to distinguish between variation and true improvement.

CMMS and EAM systems reinforce this through workflows, approvals and version control.

Sustained improvement depends not on constant change, but on disciplined evolution.

Leadership And The Long View.

Continuous Improvement is ultimately a leadership choice. It requires patience, investment and a willingness to prioritise long‑term performance over short‑term convenience.

Maintenance Leaders must create space for analysis, support capability development and reinforce discipline even when pressures mount.

When leadership commitment is genuine, Continuous Improvement becomes self‑reinforcing. Teams see the impact of their efforts, trust the systems they use and contribute actively to organisational learning.

The Operating System of Maintenance.

When fully embedded, Continuous Improvement becomes the operating system of maintenance and asset management.

It connects people, processes and technology into a coherent, learning‑driven system. CMMS, EAM and ERP platforms become more than tools, they become vehicles for insight and institutional memory.

In a world where assets age, risk evolves and expectations rise, Continuous Improvement is not optional. It is how maintenance organisations remain reliable in an unreliable world and how asset performance is sustained not by chance, but by design.