Corrective And Breakdown Work For Small Business CMMS

Disclaimer.

This article provides general guidance on maintenance work classification and CMMS usage for informational purposes only.

It does not constitute professional advice tailored to specific business circumstances. Maintenance processes, safety requirements and regulatory compliance vary by industry, jurisdiction and asset type.

Readers should consult qualified maintenance professionals, safety experts and legal advisors before implementing any maintenance management system or process.

The information presented reflects general industry practices and may not suit all operational contexts.

No warranty is made regarding the accuracy, completeness or suitability of this information for any particular purpose.

The ideas, thoughts, views and opinions expressed are those of the author only.

Article Summary.

Small businesses face unique challenges in maintenance management.

Limited budgets often mean working with affordable CMMS solutions rather than enterprise-grade systems.

However, an inexpensive CMMS used effectively can deliver substantial value when fed clean, structured information. The key lies not in the sophistication of the software but in the clarity of the work identification process.

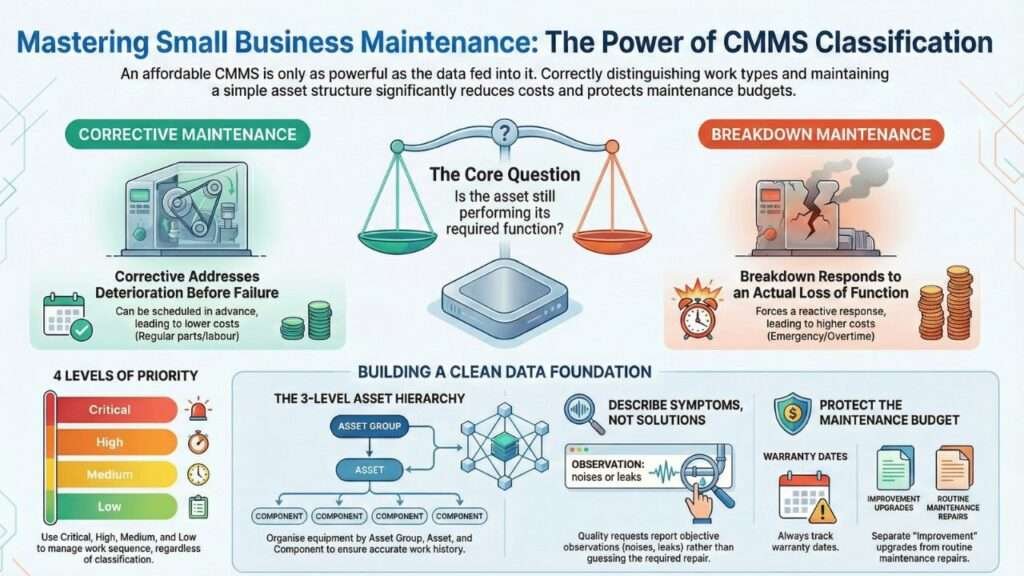

This article explains how to distinguish between corrective and breakdown maintenance work, build a simple asset structure, set appropriate priorities and create high-quality maintenance requests.

It provides practical guidance on validating work before it begins, identifying improvement work separately from repairs and tracking warranty information to avoid unnecessary spending.

Correct classification of maintenance work enables better planning, reduces costs, improves safety and builds reliable maintenance data over time.

Even basic CMMS solutions become powerful tools when organisations establish clear, repeatable processes for identifying and recording maintenance needs.

Top 5 Takeaways.

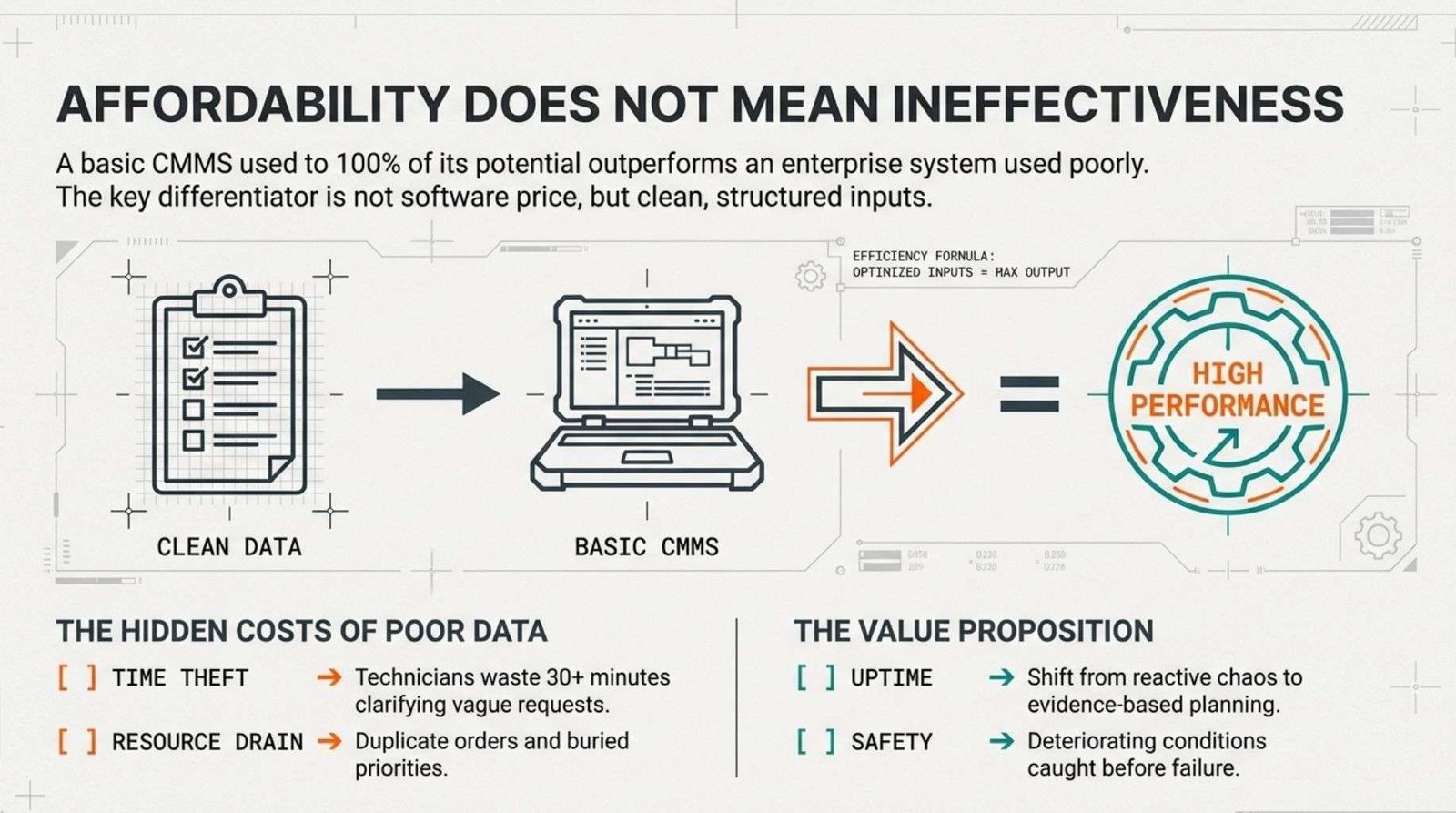

1. An affordable CMMS used to 100% of its potential is more practical than an expensive system used poorly. Clean, structured inputs matter more than software sophistication.

2. Corrective maintenance addresses deterioration before failure occurs, while breakdown maintenance responds to actual loss of function. Understanding this distinction enables better planning and resource allocation.

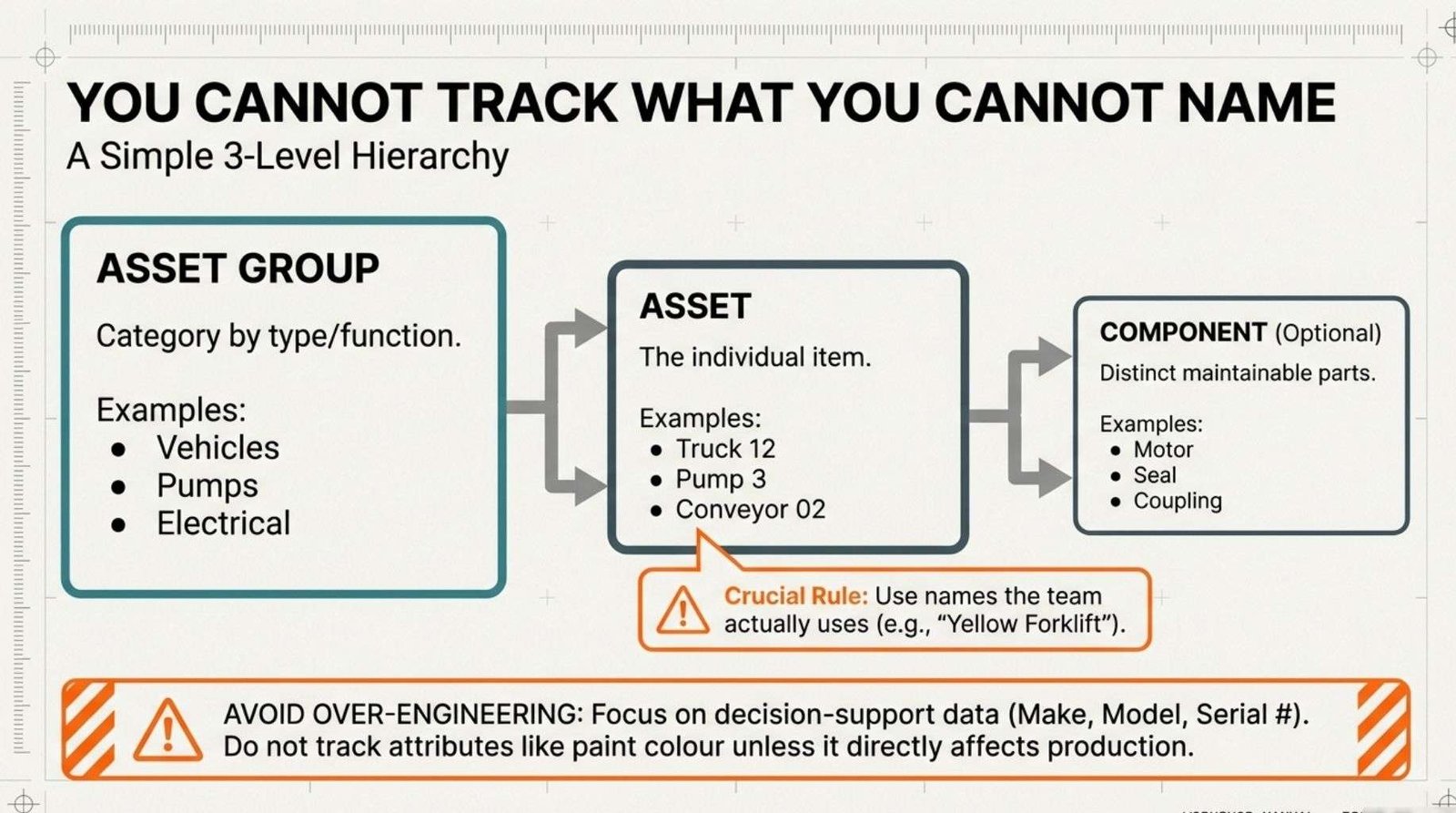

3. A simple three-level asset structure (Asset Group, Asset, Component) provides sufficient organisation for most small businesses without creating unnecessary complexity.

4. The core question for work classification is: “Is the asset still performing its required function?” If no, it is breakdown work. If yes, it is corrective work.

5. Many businesses waste maintenance budget on warranty-eligible work. Tracking warranty information in your CMMS ensures claims are filed when appropriate, protecting budget resources.

Table of Contents.

1.0 Small Businesses Need Clear Processes for Corrective & Breakdown Work.

2.0 What “Corrective” and “Breakdown” Maintenance Really Mean.

3.0 Three Inputs That Trigger Maintenance Work.

4.0 Building a Simple Asset Structure.

5.0 How to Decide Whether Work Is Corrective or Breakdown.

6.0 Setting Priorities Without Overcomplicating It.

7.0 Creating a Quality Maintenance Request.

8.0 Validating Requests Before Work Begins.

9.0 Identifying Improvement/Upgrade/Modification Work.

10.0 Warranty Considerations for Small Businesses.

11.0 Correct Classification Can Improve Your Maintenance Strategy.

12.0 Conclusion.

13.0 Bibliography.

1.0 Clear Processes for Corrective & Breakdown Work.

Small businesses often cannot afford top-tier CMMS solutions.

This reality is why the market offers such a wide range of maintenance management software, from very affordable products to expensive enterprise systems. The cost differential reflects varying feature sets, scalability and support levels. However, affordability does not mean ineffectiveness.

A basic CMMS used to 100% of its potential delivers substantial value.

When organisations establish clear processes for identifying and recording maintenance work, even simple software becomes a powerful asset management tool. If process gaps exist, businesses can integrate bolt-on third-party software products to address specific needs. This modular approach often performs better than underutilising expensive systems.

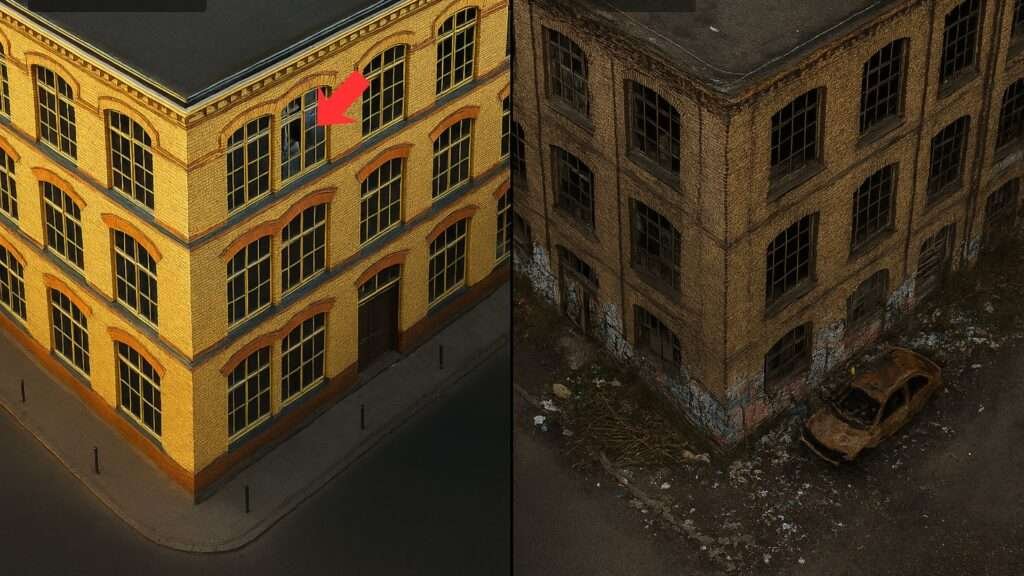

1.1 The Hidden Cost Of Poor Work Identification In Small Operations.

Poor work identification can potentially create multiple hidden costs.

Maintenance teams waste time investigating vague requests or duplicating work already completed. Parts get ordered for the wrong equipment.

Urgent work gets buried under non-critical tasks because everything carries the same priority. Preventable failures occur because early warning signs were logged incorrectly and never addressed.

In small operations where every hour of downtime matters and maintenance staff handle multiple responsibilities, these inefficiencies compound quickly.

A maintenance technician spending 30 minutes clarifying a poorly written work request represents not just lost productivity but potentially delayed response to genuine urgent needs elsewhere.

1.2 Even A Basic CMMS Becomes Powerful When Fed Quality information.

CMMS software stores and organises maintenance information. The quality of outputs depends entirely on the quality of inputs.

A basic system with clean data enables accurate work history reviews, identifies problem assets, tracks costs per equipment item and supports evidence-based maintenance planning.

Clean, structured information means:

1. Consistent asset identification.

2. Clear problem descriptions.

3. Accurate work classification.

4. Appropriate priority assignment.

5. Complete documentation.

When these elements are present, even simple CMMS solutions generate reliable reports, support scheduling decisions and build institutional knowledge that survives staff turnover.

1.3 Correct Classifications Can Improves Uptime, Safety And Planning.

Correct work classification enables maintenance teams to distinguish between reactive and proactive work.

This distinction matters because it affects resource allocation, scheduling decisions and long-term reliability improvement efforts.

Uptime improves when teams identify and address corrective issues before they become breakdowns. Safety improves when deteriorating conditions receive timely attention rather than progressing to hazardous failures.

Planning improves when the maintenance backlog accurately reflects work type, urgency and resource requirements.

A small manufacturing business that consistently classifies work correctly can identify which assets consume the most breakdown maintenance hours.

This information supports decisions about preventive maintenance frequency, parts inventory and eventual replacement timing.

1.4 The Goal Is A Simple, Repeatable Process That Works.

The process described in this article applies across CMMS platforms. Whether using free open-source software, a low-cost cloud solution or a mid-range system, the fundamental steps remain consistent.

The goal is establishing a workflow that any team member can follow to correctly identify, classify and record maintenance needs.

Simplicity and repeatability matter more than sophistication. A straightforward process that gets followed consistently outperforms a complex system that staff find confusing or burdensome.

2.0 What “Corrective” and “Breakdown” Maintenance Really Mean.

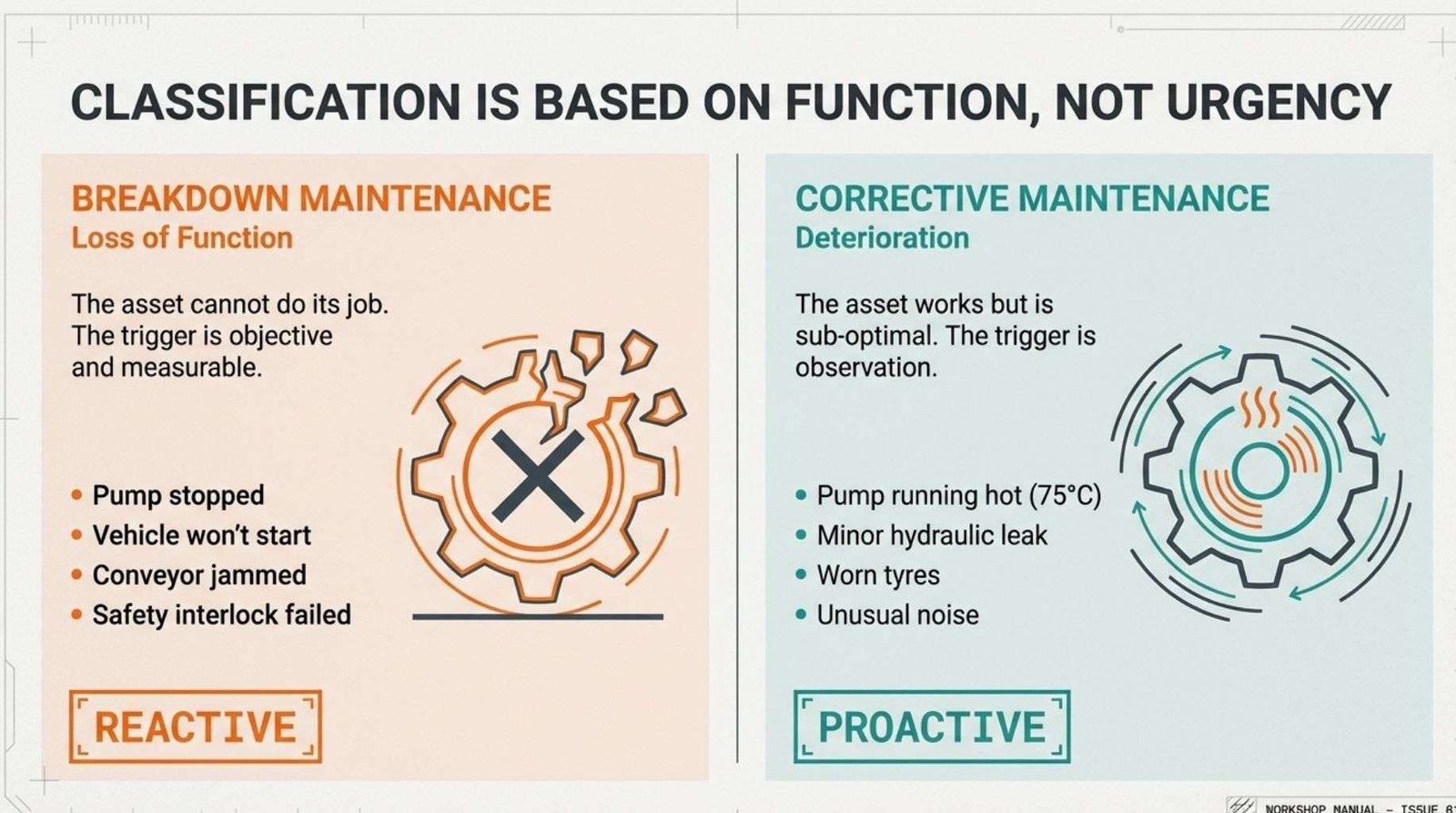

Understanding the difference between corrective and breakdown maintenance provides the foundation for effective work classification.

These terms describe when and why maintenance occurs, not necessarily how urgent the work is.

2.1 Corrective Maintenance (Secondary Work).

Corrective maintenance addresses deterioration, defects or sub-optimal conditions discovered before complete failure occurs.

This work type restores assets to acceptable operating condition while the asset continues performing its required function.

2.1.1 Inspections, Observations And Early Signs Of Deterioration.

Corrective work originates from someone noticing a problem during normal operations or planned inspections.

The asset still works but shows signs of degradation, another way of describing it would be that it no longer performs at specification.

Examples include unusual noises, minor leaks, visible wear, slight performance decline or conditions that do not yet prevent operation but will worsen without intervention.

This work type depends on observation skills and reporting culture.

If operators and technicians notice and report early warning signs, the maintenance team gains opportunities to schedule corrective work during convenient windows rather than responding to emergency failures.

2.1.2 Restore The Asset Before Failure.

The primary objective of corrective maintenance is preventing breakdowns.

By addressing issues in their early stages, organisations avoid the costs, safety risks and operational disruptions associated with complete failures.

Corrective work also prevents secondary damage. A slightly worn bearing that receives timely replacement avoids damaging the shaft it supports.

A small hydraulic leak that gets repaired prevents contamination of surrounding components and environmental issues.

Examples:

Small business operations would encounter corrective maintenance needs across various asset types such as:

1. Loose drive belts on production equipment.

2. Minor hydraulic leaks on material handling machinery.

3. Worn tyres on delivery vehicles.

4. Deteriorating door seals on refrigeration units.

5. Cracked v-belts showing signs of fraying but still functioning.

6. Bearings producing unusual noise but not yet seized.

7. Air compressors taking longer to reach pressure but still operational.

8. Forklift steering with increased play but still controllable.

9. Office air conditioning units cooling adequately but making grinding sounds.

Each example represents work that should occur soon but does not require immediate stoppage of operations.

2.2 Breakdown Maintenance.

Breakdown maintenance responds to loss of function. The asset has failed to perform its required task or has stopped working entirely.

2.2.1 Work Triggered By Failure or Loss Of Function.

Breakdown work begins the moment an asset can no longer perform its intended function. This may be a complete stoppage, operation outside acceptable limits, or the creation of unsafe conditions that prevent normal use.

In many low‑tolerance processes, operating outside specification by even a small percentage is just as disruptive as a total failure. The defining feature is that the trigger is objective and measurable.

Examples include:

· The pump has stopped pumping.

· The vehicle will not start.

· The conveyor is jammed.

· The equipment is producing defective output.

· The safety interlock has failed.

2.2.2 Why Breakdowns May Not Be Always Urgent.

While breakdown maintenance means the asset has failed, it does not automatically mean the work requires immediate response.

Urgency depends on operational context.

A breakdown on a backup generator in summer may receive low priority if the primary power system operates reliably.

A breakdown on the same generator during severe weather becomes urgent.

A failed overhead crane in a facility with three operational cranes creates a different urgency level than a single-crane facility.

The classification as breakdown work describes the nature of the problem (loss of function) rather than dictating response timeframe.

Priority setting should consider broader operational needs.

Examples.

Breakdown maintenance examples include:

1.0 Pump stops circulating coolant.

2.0 Delivery vehicle will not start.

3.0 Conveyor jams and cannot move product.

4.0 Compressed air system drops below minimum required pressure.

5.0 Milling machine spindle seizes.

6.0 Forklift hydraulic system loses all pressure.

7.0 Office HVAC unit stops completely.

8.0 Production line safety guard fails and prevents operation.

9.0 Computer server crashes.

Each example represents complete or partial loss of required function, distinguishing it from corrective work where the asset still operates despite showing deterioration.

2.3 Why The Distinction Matters In A Small Business.

Small businesses face resource constraints that make efficient maintenance management particularly important.

The distinction between corrective and breakdown work affects multiple operational aspects.

2.3.1 Planning Versus Reacting.

Corrective maintenance allows planning. The work can be scheduled during low-demand periods, coordinated with parts availability and assigned to appropriate technicians based on skills and workload.

Breakdown maintenance forces reaction. Even when a breakdown receives a low priority assignment, it still represents unplanned work that disrupts scheduled activities and may require immediate resource reallocation.

A small business that captures and addresses corrective work effectively reduces the proportion of reactive breakdown work in its maintenance portfolio. This shift enables better resource utilisation and reduces operational disruptions.

2.3.2 Cost Differences.

Corrective work typically costs less than breakdown work for the same underlying issue. Parts can be sourced at regular prices rather than emergency expedited costs. Labour can be scheduled during regular hours rather than overtime. Production losses may be avoided entirely if work occurs during planned downtime.

Breakdown work often includes costs beyond the immediate repair. Lost production, expedited shipping, overtime labour, secondary damage and customer impacts all contribute to the total cost of failure.

A bearing replacement scheduled as corrective work might cost a few hundred dollars in parts and just a couple of hours of regular-time labour.

The same bearing replacement after catastrophic failure could include the original costs plus damaged shaft replacement, expedited part shipping, 6 hours of overtime labour and unplanned lost production valued at great cost to the business.

2.3.3 Impact On scheduling And Resource Allocation.

Maintenance teams with a large proportion of corrective work in their backlog can plan weekly schedules more effectively.

They know what work needs completion, can ensure parts availability and can balance workload across available staff.

Maintenance teams dominated by breakdown work operate in constant reactive mode. Schedules change continuously, parts get expedited frequently and staff experience high stress levels from perpetual urgency.

The distinction matters because it enables measurement. By tracking the proportion of corrective versus breakdown work over time, small businesses can assess whether their maintenance approach is improving asset reliability or merely reacting to failures.

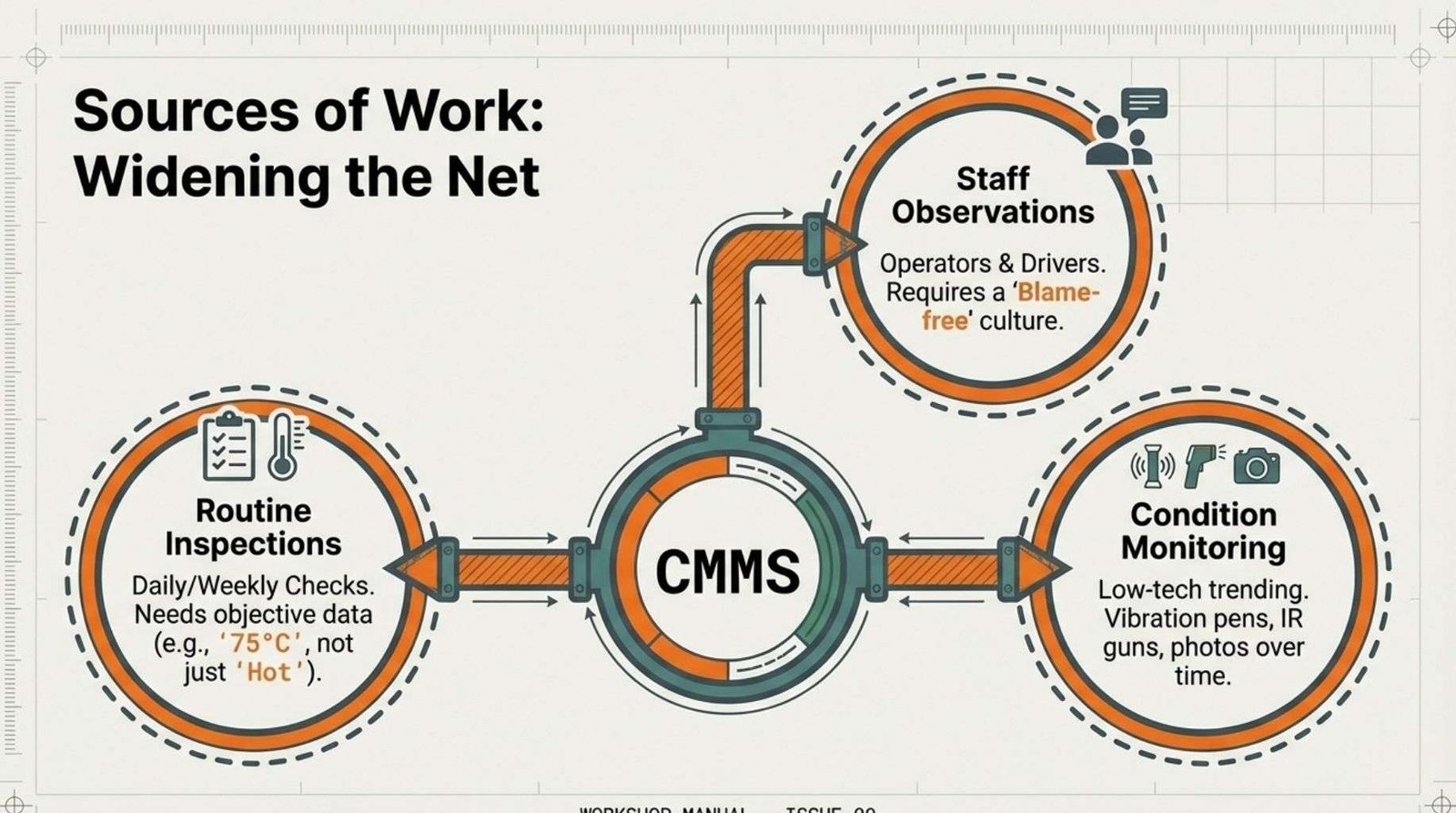

3.0 Three Inputs That Trigger Maintenance Work.

Maintenance work typically originates from three primary sources.

Understanding these inputs helps organisations develop appropriate processes for each type and ensure nothing gets overlooked.

3.1 Staff Observations.

Operators, drivers and technicians represent the front line of asset condition awareness. They interact with equipment daily and often notice changes before formal inspections occur.

3.1.1 Operators, Drivers, Technicians.

Operators run production equipment and notice performance changes, unusual behaviours or abnormal sounds.

Drivers use vehicles daily and detect handling issues, strange noises or warning indicators. Technicians performing routine tasks observe equipment across the facility and spot developing problems.

Each group brings valuable perspective. Operators understand normal equipment behaviour and recognise deviations. Drivers experience vehicle performance directly. Technicians see patterns across multiple assets and compare conditions.

3.1.2 How To Encourage Reporting Culture.

Staff report problems when they trust that reports lead to action, understand what to report and find the reporting process simple.

Building reporting culture requires:

1. Acknowledging reports promptly.

2. Providing feedback on actions taken.

3. Making reporting easy (mobile access, simple forms).

4. Training staff on what conditions warrant reporting.

5. Never penalising legitimate problem reports.

Some organisations implement reward systems for identifying problems before they become failures.

Others incorporate observation reporting into performance expectations. The specific approach matters less than consistent reinforcement that noticing and reporting problems represents valued contribution.

3.2 Routine Inspections.

Scheduled inspections provide systematic examination of assets on defined intervals. Even small businesses benefit from basic inspection routines.

3.2.1 Daily/Weekly Checks.

Daily checks address safety-critical items and high-use assets.

Examples include vehicle pre-start inspections, production equipment safety guard verification and emergency equipment readiness checks.

Weekly checks cover broader asset populations with less frequency than warranted for daily review but more than monthly intervals provide.

Examples include general equipment walkarounds, fluid level checks and basic performance verification.

The frequency depends on asset criticality, failure consequences and rate of condition change. High-speed production equipment may warrant daily inspection while office HVAC units receive monthly attention.

3.2.2 What Do Good Inspection Notes Look like?

Good inspection notes provide specific, objective information that enables informed decisions about required actions.

Poor inspection note: Pump seems different.

Good inspection note: Pump 3 bearing housing temperature measured 75°C, normally runs 50-55°C. Slight vibration felt when touching pump casing. No visible leaks or unusual sounds.

The good example provides measurable information (temperature), context (normal range), specific location (bearing housing) and additional observations (vibration, no leaks). This information supports accurate work classification and priority assignment.

Inspection notes should describe observed conditions rather than propose solutions. “Bearing housing hot” describes the condition. “Replace bearing” proposes a solution that may or may not address the underlying cause.

3.3 Condition Monitoring (Even Basic Forms).

Condition monitoring tracks asset parameters over time to detect trends toward failure. While sophisticated systems exist, even basic approaches provide value.

3.3.1 Simple Examples: Temperature, Noise, Vibration, Fluid levels.

Small businesses can implement basic condition monitoring without expensive equipment:

1. Temperature: Infrared thermometers or temperature strips identify hot spots.

2. Noise: Trained ears detect changes in sound character or volume.

3. Vibration: Hand-feel methods identify increasing vibration levels.

4. Fluid levels: Regular checks detect consumption rate changes.

5. Visual: Photographs document wear progression.

These simple methods detect deterioration when applied consistently.

A weekly bearing temperature check that shows gradual increase over several weeks provides early warning of impending failure.

3.3.2 How Even Low-Tech Monitoring Supports Early Detection.

Even very simple tools can underpin highly effective condition monitoring when they are used consistently and the results are trended over time rather than treated as one‑off checks.

A pump vibration level might look acceptable in isolation, but it becomes a concern when it has risen by more than XX% over the past month.

Regular readings, even from basic instruments, create a practical baseline. Once that baseline exists, small deviations stand out and can be linked to emerging faults such as imbalance, misalignment or deteriorating bearings, well before they cause a breakdown.

Many years ago, plants often achieved this with nothing more sophisticated than a vibration pen and an infrared temperature gun.

Technicians would press the vibration pen into machined dimples on bearing housings, walk the plant with a temperature gun, and manually transfer those readings into a spreadsheet after the round.

The process was low‑tech and labour‑intensive, but it enabled reliable trending and early identification of “something’s changing” long before failure.

I’m not suggesting that these readings should be recorded in a spreadsheet instead of your CMMS. The point is to illustrate how simple the underlying principles can be.

Most affordable CMMS platforms now include basic condition monitoring functionality, and if yours doesn’t, there are standalone bolt‑on tools that can often be integrated. The important part is the discipline of capturing repeatable readings and trending them over time.

A small manufacturing shop that checks key equipment temperatures weekly using a low‑cost infrared thermometer and logs results, whether in their CMMS or a simple digital form, has in effect, implemented basic condition monitoring.

This approach consumes minimal resources but still delivers the most important benefit of any monitoring program: visibility of trends that justify corrective work before unplanned downtime occurs.

4.0 Building A Simple Asset Structure.

Asset structure determines how equipment is organised and identified within the CMMS. A well-designed structure improves data quality and supports effective reporting.

4.1 Why Structure Matters.

Asset structure affects every interaction with the CMMS. Users select assets when creating maintenance requests.

Reports group information by asset categories. Work history accumulates against specific asset records.

4.1.1 Helps Users Pick The Right Asset.

A clear structure enables users to quickly locate the correct equipment when logging problems.

This reduces errors from selecting wrong assets and ensures work history accumulates against the proper records.

If users struggle to find the right asset in the system, they may select the closest match or create duplicate records.

Both outcomes corrupt data quality and reduce the CMMS value.

4.1.2 Improves Reporting And History.

Good structure supports meaningful reports. Management can view maintenance costs by asset type, identify problem equipment and track work history reliably.

Cumulative work history against correctly identified assets reveals patterns.

An asset with frequent breakdown work may warrant more aggressive preventive maintenance or replacement consideration. This analysis depends on accurate, consistent asset identification.

4.1.3 Makes Future Strategy Work Possible.

As maintenance maturity grows, organisations develop more sophisticated strategies like reliability-centred maintenance or condition-based maintenance.

These approaches require clean historical data linked to properly identified assets. Starting with sound asset structure avoids future rework when advancing maintenance strategy.

4.2 A Three-Level Structure For Small Businesses.

A practical starting point is a three‑level hierarchy:

Asset Group → Asset → (optional) Sub‑Asset or Location.

This is easy to understand, quick to set up and still supports sensible reporting and planning.

Level 1: Asset Group.

Asset groups categorise equipment by type or function. Common groups include:

1. Vehicles.

2. Pumps.

3. Electrical.

4. Buildings.

5. Production Equipment.

6. Material Handling.

7. HVAC.

8. IT Equipment.

Groups are typically of highest value when they mirror how the business naturally talks about its equipment.

If there is a distinct vehicle fleet operation, “Vehicles” is a natural group; if electrical work is handled separately, “Electrical” warrants its own group.

As general rule, most small businesses will end up with around 5–12 asset groups: too few creates catch‑all buckets that hide important differences, while too many adds admin burden without corresponding benefit.

Level 2: Asset.

Assets are the individual items of equipment. Each asset receives a unique identifier within its group, and the naming convention is simple, clear and consistently applied.

Examples include:

· Truck 12.

· Pump 3.

· Workshop A/C Unit.

· Finished Product Line 2 Conveyor.

· Forklift FL‑04.

The identifier can include sequential numbers, location references or functional descriptors.

The important thing is that once a pattern is chosen, it is used everywhere: if vehicles use numbers, all vehicles should follow that pattern; if conveyors use line numbers, all conveyors use that same scheme.

Each asset record should then store key information such as:

1. Make and model

2. Serial number

3. Installation or in‑service date

4. Warranty information

5. Criticality rating

6. Physical location

This level of detail is usually enough to plan work, track cost and support basic reliability analysis in a small operation.

Level 3: Sub‑Asset or Location (optional but helpful).

For some assets, it is useful to define one additional level to distinguish major sub‑items or precise locations without building a full enterprise‑grade hierarchy. This might include:

· Sub‑components: “Pump 3 – Motor”, “Pump 3 – Coupling”, “Pump 3 – Mechanical Seal”

· Location points: “Workshop A/C Unit – Outdoor Condenser”, “Finished Product Line 2 Conveyor – Tail End”

This third level is optional and should only be used where it genuinely improves maintenance planning, failure analysis, or safety. An example of this is when different parts of the same asset have different inspection regimes.

Component‑level tracking makes sense when:

1. The asset is complex with distinct subsystems.

2. Components receive individual maintenance.

3. Failure patterns differ significantly between components.

4. Warranty or replacement tracking is component‑specific.

Many small businesses operate effectively without this level of detail.

A delivery truck tracked simply as “Truck 12” accumulates a perfectly adequate work history. Adding components such as engine, transmission, and braking system provides more insight but also increases data entry effort.

The decision comes down to whether the extra detail supports better maintenance decisions. If the answer is unclear, start without component‑level tracking and add it later if needed.

When component tracking adds value, typical examples include:

1. Vehicle: Engine, Transmission, Braking System, Electrical System

2. Pump: Motor, Coupling, Pump Head, Seal Assembly

3. Air Compressor: Compressor Head, Motor, Air Dryer, Control System

4. Production Equipment: Drive System, Control Panel, Tooling, Safety Guards

Components should represent maintainable subsystems, not individual small parts. Tracking bolts, washers, or minor fittings creates administrative burden without meaningful benefit.

4.3 Practical Tips.

Several practical considerations help maintain effective asset structure.

4.3.1 Keep It Simple.

Asset structure should be as simple as possible while meeting organisational needs. Every additional level or category increases data entry effort and creates more opportunities for errors.

Start with minimal structure and add complexity only when clear benefits emerge. A business with 20 assets needs less elaborate structure than one with 200 assets.

4.3.2 Avoid Over Engineering Your CMMS Asset Data.

Over-engineered asset structures fail because users find them burdensome.

Ten required fields per asset record means incomplete data when five fields would suffice.

Focus on information that supports maintenance decisions. Equipment manufacturer, model and serial number matter.

Paint colour generally does not unless the business manufactures painted products where colour tracking affects production planning.

4.3.3 Use Names Your Team Already Uses (Known As).

Asset names should match shop floor terminology. If everyone calls the warehouse forklift “Yellow Forklift” despite it being a “Clark C25D” model, the CMMS should reference it in a way that connects to common usage.

This does not mean abandoning proper identification. The asset record can include both the official model designation and the common nickname. What matters is that users can find the right asset without confusion.

5.0 How to Decide Whether Work Is Corrective or Breakdown.

Work classification requires a systematic approach based on objective criteria rather than subjective judgment.

5.1 The Core Question.

One question determines the classification: “Is the asset still performing its required function?”.

This question focuses on functional capability rather than optimal performance. The key word is “required”.

Assets may perform suboptimally yet still fulfill basic functional requirements. This distinction separates corrective from breakdown work.

5.2 If NO → Breakdown.

When an asset cannot perform its required function, the work is classified as breakdown maintenance, regardless of why the failure occurred or how urgent the response is.

Examples of breakdown work triggered by loss of function.

1. Pump required to maintain cooling flow has stopped → Breakdown

2. Delivery vehicle will not start → Breakdown

3. Conveyor required to move product is jammed → Breakdown

4. Air compressor cannot maintain minimum system pressure → Breakdown

5. Safety guard damaged and preventing machine operation → Breakdown

o (This also applies if the guard is missing.)

Each example represents a clear inability to perform the required task. The pump must circulate coolant but cannot.

The vehicle must transport goods but will not start. The conveyor must move product but is jammed.

5.2.1 What to Record in the CMMS.

Breakdown work orders should capture the minimum essential information needed for both immediate repair and long‑term failure analysis.

The goal is clarity, not volume.

Consider Record The following:

1. Specific function that has failed

o What the asset was supposed to do but could not.

2. Symptoms observed

o What the technician saw, heard, smelled, or measured.

3. When the failure occurred

o Timestamp or operating context.

4. Operational impact

o What was affected (production, safety, quality, etc.).

5. Immediate actions taken

o Lockout, shutdown, temporary workaround, etc.

6. Failed component (What failed)

o The specific part or subsystem that lost function.

7. Failure mode (How it failed)

o Seized, leaking, jammed, burnt out, cracked, etc.

8. Probable cause (Why it failed)

o Misalignment, contamination, wear‑out, incorrect installation, etc.

9. Corrective action (What was done)

o Replace bearing, realign motor, replace seal, etc.

These last four items are the core of failure analysis and align with industry best practice (RCM, FRACAS, ISO 14224). They allow patterns to emerge over time without requiring a full RCA for every event.

Example Entry.

“Pump 3 stopped circulating coolant to Production Line 2 at 10:15 AM. Line shut down to prevent overheating. No unusual noise or leaks observed prior to failure. Pump will not restart. Failed component: motor. Failure mode: winding short. Probable cause: moisture ingress. Corrective action: replaced motor and dried enclosure.”

This level of documentation provides immediate context for the repair and builds a reliable dataset for identifying recurring failure patterns.

5.3 If YES → Corrective.

When the asset continues performing its required function but shows signs of deterioration, the work is classified as corrective maintenance.

Examples Of Corrective Work Where Function Is Maintained.

1. Pump circulating coolant adequately but bearing housing temperature elevated → Corrective

2. Vehicle starting and running but producing unusual engine noise → Corrective

3. Conveyor moving product but drive belt showing cracks → Corrective

4. Air compressor maintaining pressure but taking longer to build pressure → Corrective

5. Equipment operating normally but safety guard slightly damaged → Corrective

Each example reflects a condition where the asset is still doing its job, but something is no longer within normal limits.

The pump still circulates coolant. The vehicle still transports goods. The conveyor still moves product. Function is intact, but deterioration is visible.

5.3.1 Identifying Corrective Work Can Prevent Future Breakdowns.

Corrective maintenance allows intervention before the asset reaches the point of failure.

1. The pump with elevated bearing temperature can receive a new bearing before it seizes.

2. The vehicle with unusual noise can be diagnosed before the engine fails.

3. The conveyor belt showing cracks can be replaced before it snaps.

This proactive approach reduces unexpected failures, lowers total maintenance costs, and improves equipment reliability.

Corrective work is the bridge between reactive breakdowns and a stable, planned maintenance environment.

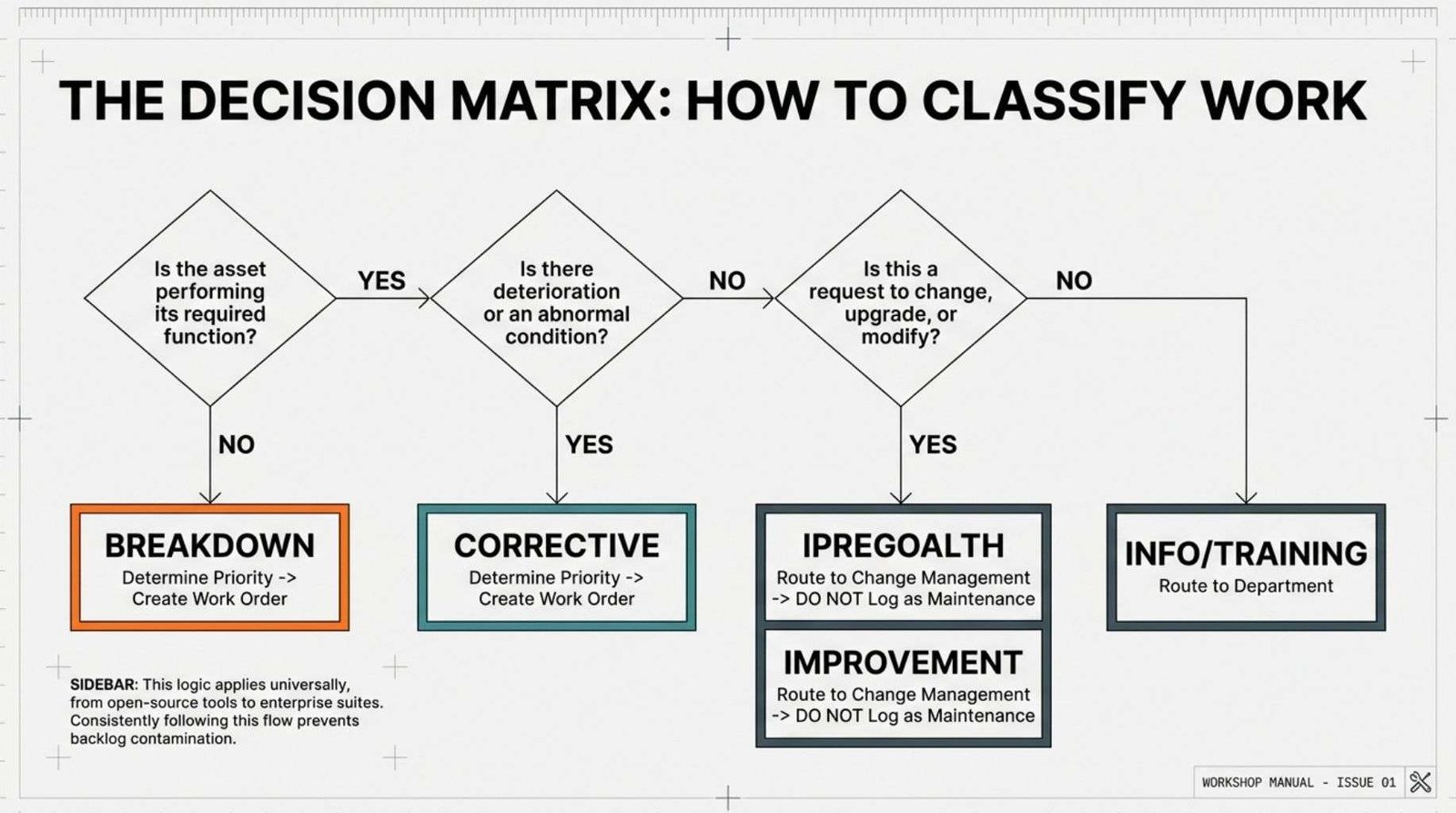

5.4 A Decision Flowchart for Small Teams.

A simple flowchart helps teams consistently classify maintenance work.

5.4.1 A Lightweight Version.

Basic flowchart for small business work classification:

1. Can the asset perform its required function? → If NO, classify as Breakdown → Determine Priority → Create Work Order.

2. Can the asset perform its required function? → If YES, continue to next question.

3. Has deterioration or abnormal condition been observed? → If YES, classify as Corrective → Determine Priority → Create Work Order.

4. Has deterioration or abnormal condition been observed? → If NO, continue to next question.

5. Is this a request to change, upgrade or modify the asset? → If YES, classify as Improvement → Route to Change Management → Do not create maintenance work order.

6. Is this a request to change, upgrade or modify the asset? → If NO, continue to next question.

7. Is this a request for information, training or non-maintenance service? → If YES, route to appropriate department → Do not create maintenance work order.

8. If none of the above apply, consult with maintenance supervisor for classification guidance.

This flowchart addresses most scenarios small businesses encounter. It can be printed on a single page, posted in work areas and used during training.

5.4.2 What Would A More Complex Flowchart Look like?

A comprehensive corrective‑and‑breakdown maintenance flowchart used in large industrial operations includes additional decision points and classifications that go far beyond the needs of most small businesses.

Typical elements in a complex, enterprise‑level flowchart might include:

1. Risk assessment at multiple decision points.

2. Regulatory and compliance checks.

3. Capital vs operational expenditure determination.

4. Detailed priority matrices with multiple weighting factors.

5. Engineering review or sign‑off requirements.

6. Management approval thresholds.

7. Integration with broader maintenance strategy frameworks (RCM, TPM, CBM)

These layers exist because large organisations manage thousands of assets, spread across multiple sites, with varying criticality levels, strict regulatory obligations, and formal governance requirements.

The complexity is not bureaucracy for its own sake, it is a structured way to manage risk at scale.

Why does this matter for small businesses?

Although small businesses might not benefit from this level of detail as their asset base is smaller, their workflows are simpler, and their decision‑making is more direct.

I believe there is value in understanding the comprehensive approach as it helps owners recognise when additional discipline might be valuable.

A small business experiencing rapid growth, facing increasing regulatory requirements, or operating highly critical equipment may eventually choose to adopt more sophisticated classification processes.

The lightweight flowchart presented earlier provides a solid foundation that can expand as organisational needs evolve.

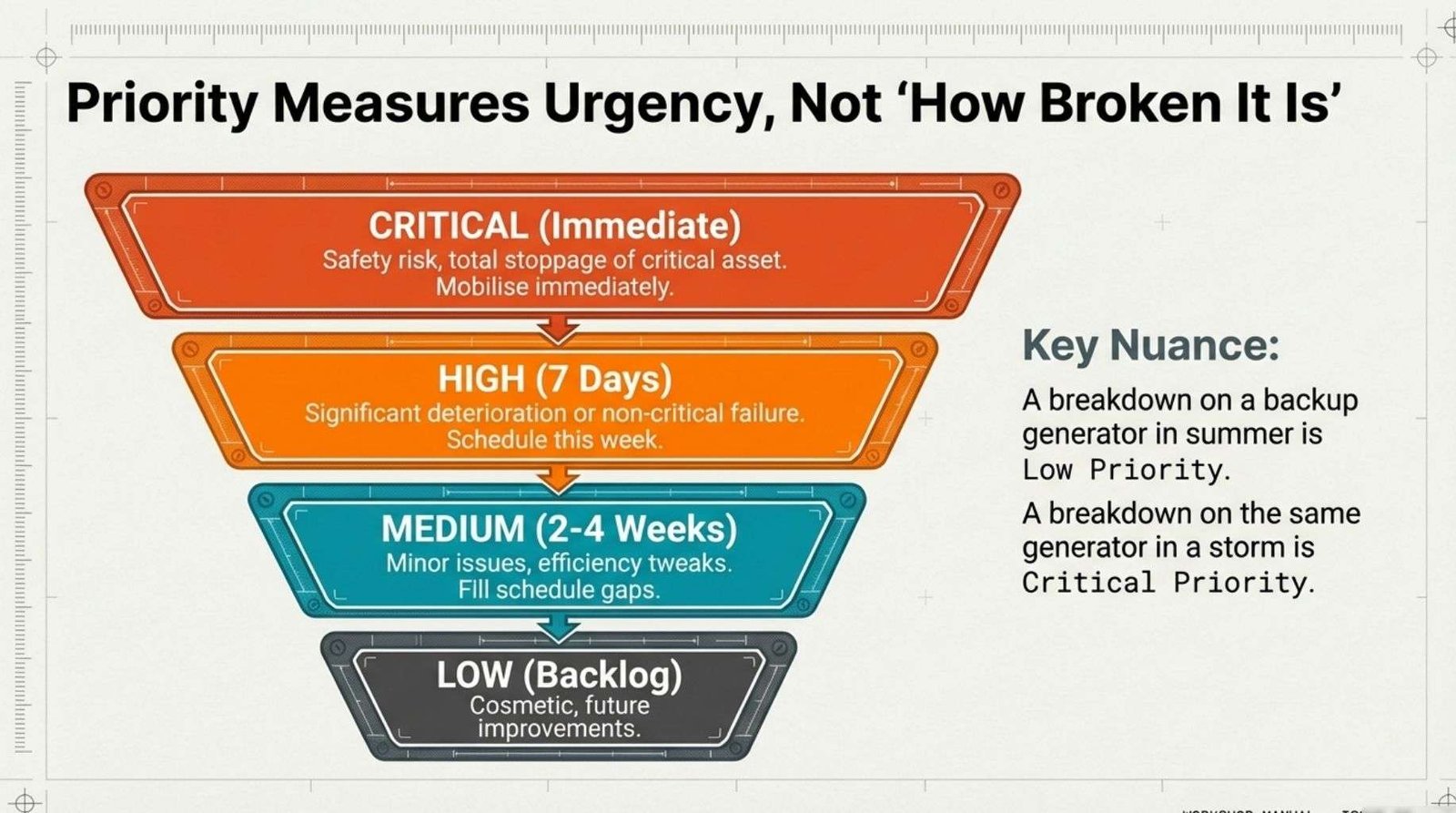

6.0 Setting Priorities Without Overcomplicating It.

Priority assignment determines work sequence and resource allocation.

Small businesses need a system simple enough for consistent application yet sophisticated enough to reflect genuine operational needs.

6.1 The Four Priority Levels For Small Businesses.

Four examples of priority levels are provided in this section. In my opinion, this information provides adequate granularity for most small operations. Additional levels might create decision paralysis without improving outcomes.

Level 1: Critical (Immediate).

Critical work requires immediate response, typically within hours. This priority applies to:

1. Safety hazards preventing asset use.

2. Complete failures of critical assets with no backup.

3. Environmental hazards requiring urgent containment.

4. Situations creating imminent risk to people or property.

Critical priority mobilises resources immediately, potentially including overtime, emergency part procurement and suspension of other planned work.

Level 2: High (Within 7 days).

High priority work needs completion within one week. This applies to:

1. Failures of important but non-critical assets.

2. Corrective work on critical assets showing significant deterioration.

3. Safety issues that can be temporarily mitigated.

4. Problems causing inefficiency but not preventing operation.

High priority work receives preference in weekly scheduling but does not typically trigger overtime or emergency measures.

Level 3: Medium (Next 2–4 weeks).

Medium priority work should be completed within 2-4 weeks.

This applies to:

1. Corrective work on non-critical assets.

2. Minor deterioration on critical assets.

3. Efficiency improvements.

4. Quality issues not affecting safety or primary function.

Medium priority work fills the maintenance schedule around critical and high priority items.

Level 4: Low (Future Work/Improvement Evaluations).

Low priority work represents future needs or improvements without urgent timelines. This applies to:

1. Minor cosmetic issues.

2. Improvement ideas for evaluation.

3. Deferred work that can wait for extended periods.

4. Work dependent on other projects or events.

Low priority items populate the backlog and receive attention during low-demand periods or when related work occurs on the same asset.

6.2 How to Choose the Right Priority.

Priority selection considers multiple factors and a simple mental checklist helps ensure consistent decisions.

6.2.1 Safety.

Safety concerns override other factors. Any condition creating immediate risk to people warrants critical or high priority regardless of operational impact.

However, not all safety-related work is urgent. A safety guard with minor damage that does not prevent proper function might be corrective medium priority work. A completely broken safety guard preventing machine operation is critical breakdown work.

The distinction depends on immediate risk level and whether temporary mitigation is possible.

6.2.2 Production Impact.

Production impact considers:

1. How many units cannot be produced.

2. How long production is affected.

3. Whether workarounds exist.

4. Customer commitments at risk.

A failed asset on a production line with no backup capability affects priority differently than a failed backup asset with primary equipment running normally.

6.2.3 Cost Of Delay.

Some problems worsen rapidly when left unaddressed. Others remain stable for extended periods. This consideration affects priority assignment.

A small hydraulic leak may warrant higher priority than initially apparent because continued operation damages expensive components. Minor bearing noise might receive lower priority if the asset runs infrequently and monitoring shows no deterioration trend.

6.2.4 Availability Of Parts And Labour.

Priority represents ideal timing based on operational needs. Actual scheduling considers resource availability.

A high priority job requiring a part with 3-week lead time cannot complete within 7 days. This does not change the priority but affects realistic completion expectations.

The work request retains high priority to ensure it receives immediate attention once parts arrive.

Some organisations distinguish between “priority” (operational urgency) and “schedule” (actual planned completion date) to reflect this reality.

6.3 Why “Breakdown” Does Not Always Mean “Critical”.

Work classification (breakdown versus corrective) describes the nature of the problem whereas ‘Priority’ describes response urgency and these are independent considerations.

A breakdown on a backup generator during normal operations might be low priority. The same breakdown during a power outage is critical.

The classification as breakdown work remains constant. The priority changes based on operational context.

Examples of non-urgent breakdown work:

1. Spare equipment failure when primary equipment operates normally.

2. Seasonal equipment failure during off-season.

3. Redundant system failure when other systems provide adequate capacity.

4. Office equipment failure with temporary workarounds available.

Recognising this distinction prevents artificial inflation of all breakdown work to critical status, which dilutes priority systems and creates excessive urgency culture.

7.0 Creating a Quality Maintenance Request.

Work request quality determines how efficiently maintenance teams respond. Good requests provide clear information that enables accurate classification, appropriate priority assignment and effective work planning.

7.1 What Every Request Should Include.

Six elements form the foundation of quality maintenance requests.

7.1.1 Asset/Equipment.

The specific asset requiring attention must be correctly identified using the CMMS asset structure. This ensures work history accumulates against the proper record.

Users should verify they have selected the correct asset before completing the request. Many CMMS platforms display asset details (location, description, photo) to confirm selection accuracy.

7.1.2 Problem Description.

The problem description explains what is wrong without proposing solutions. This distinction matters because the requester may not have diagnostic expertise to identify root causes.

Good problem description: “Pump 3 making loud grinding noise from rear bearing area, noticeably louder than normal operation, started approximately 2 hours ago”.

Poor problem description: “Pump 3 needs new rear bearing”.

The good description provides symptoms and context. The poor description jumps to a conclusion that may or may not address the actual problem.

The technician assigned to investigate may discover the noise originates from a different source or that bearing replacement represents only partial solution to a larger issue.

Describing problems rather than proposing solutions also helps identify duplicate requests. Multiple people might propose different solutions to the same underlying problem. Describing symptoms makes the duplication apparent.

7.1.3 Symptoms.

Detailed symptoms help technicians prepare appropriately and may enable accurate diagnosis without site visits.

Useful symptom information includes:

1. What changed from normal operation.

2. When the change occurred.

3. Whether the problem is constant or intermittent.

4. Any unusual sounds, smells, vibrations or temperatures.

5. Error messages or warning lights.

6. Recent events that might relate to the problem.

Example: “Conveyor stopped moving product at 2:15 PM. Drive motor running but belt not moving. No unusual sounds. Yesterday afternoon maintenance replaced worn rollers at discharge end”.

This symptom description provides timing, specific failure mode and potentially relevant recent work. The recent roller replacement may or may not relate to the current problem, but the technician benefits from knowing this context.

7.1.4 Photos (if possible).

Mobile CMMS access (if you have it) enables photo attachment directly from smartphones or tablets. Photos document conditions more effectively than descriptions alone.

Helpful photos include:

1. Overall view of affected asset.

2. Close-up of specific problem area.

3. Gauge readings or error displays.

4. Leaks or damage.

5. Comparison photos showing normal versus current condition.

A photo showing fluid pooling beneath equipment provides immediate insight into leak location and severity.

A photo of an error code on a control panel enables technicians to research the issue before visiting the site.

Photos also create accountability and prevent disputes about pre-existing conditions versus new damage.

7.1.5 Priority.

The requester should propose a priority based on operational impact, if they understand the process that’s great; otherwise it’s their best guess. Although it’s fair to assume that they could always ask someone in the production team for help with the operational impact.

The maintenance team validates and adjusts priority during the validation process if needed. Sometimes the request reviewers consist of someone from both maintenance and production.

Requiring the requester to consider priority encourages thoughtful assessment of urgency and helps maintenance teams understand operational perspectives.

Some organisations might provide priority selection guidance within the CMMS interface, displaying criteria for each priority level to support consistent assignment.

Reporter Name.

Contact information for the person submitting the request enables follow-up questions and provides accountability for request quality.

If the problem description lacks clarity, the maintenance team can contact the reporter for additional information. If photos would help, the reporter can be asked to provide them. If the problem resolves spontaneously, the reporter can confirm this and prevent unnecessary work.

Reporter tracking also identifies individuals who consistently submit high-quality requests (who might serve as examples for training) and those who might benefit from additional guidance.

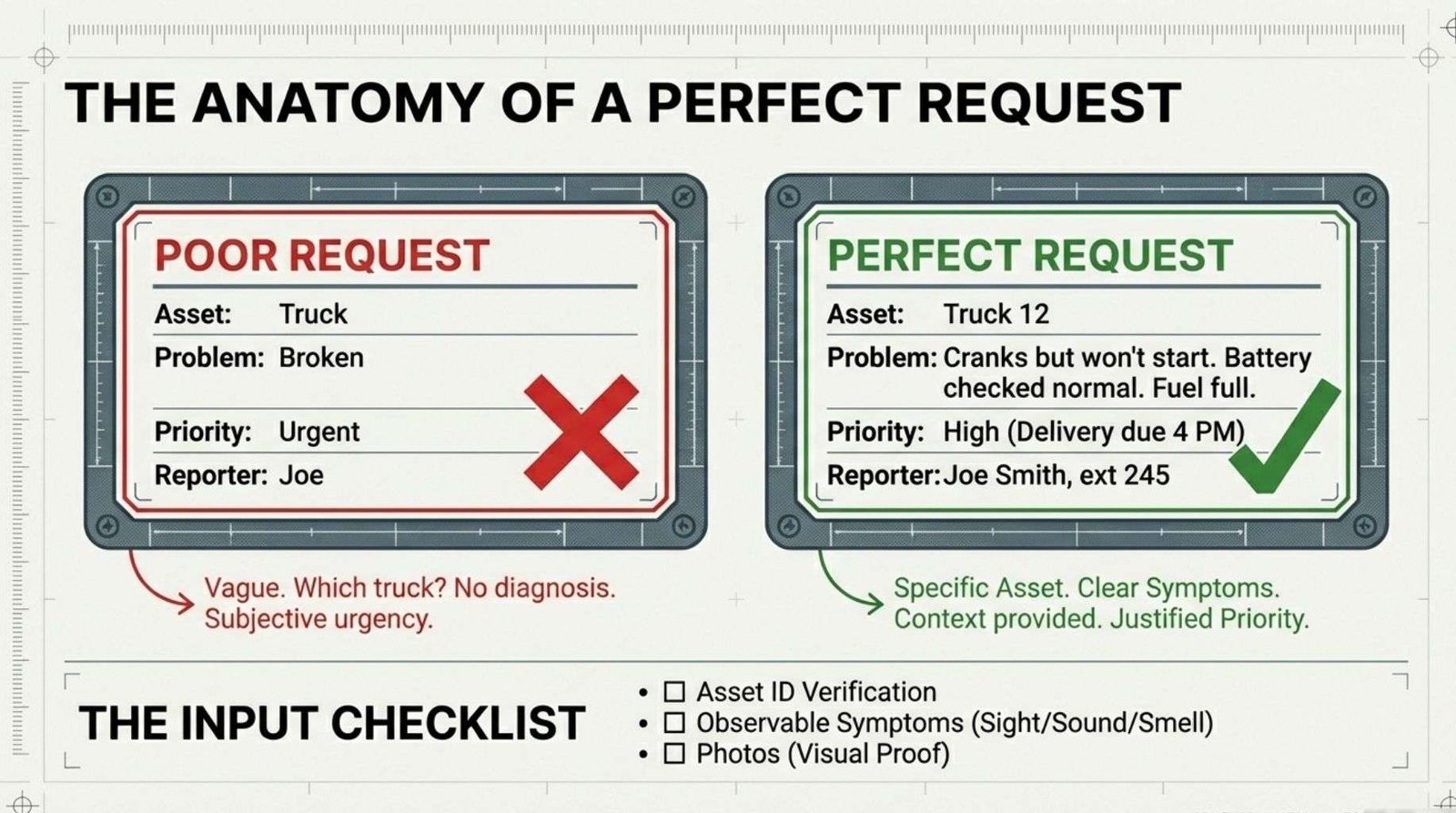

7.2 Examples Of Good Vs Poor Work Requests.

Comparing good and poor requests illustrates the principles of quality request creation.

7.2.1 Poor Work Request Example.

Asset: Truck. Problem: Broken. Priority: Urgent. Reporter: Joe.

This request lacks specificity at every level. “Truck” does not identify which vehicle. “Broken” provides no diagnostic information. “Urgent” does not explain why. “Joe” might refer to multiple employees.

A technician receiving this request must contact Joe to determine which truck has what problem and whether the urgency is genuine. This interaction wastes time for both parties.

7.2.2 Good Request Example.

Ø Asset: Delivery Truck 12.

Ø Problem: Vehicle will not start.

o Engine cranks normally but does not fire.

o Started normally this morning for warehouse run.

o Failed to start after lunch break.

o No warning lights before failure.

o Battery gauge shows normal charge.

o Fuel tank half full.

Priority: High – vehicle scheduled for customer delivery at 4 PM today, no backup vehicle available.

Reporter: Joe Smith, ext 245. Photo attached: Dashboard showing normal gauge readings.

This request provides specific asset identification, detailed symptom description, timeline, relevant context, justified priority and complete contact information. The attached photo documents the condition.

A maintenance person receiving this request could begin diagnostic preparation immediately. The symptoms suggest fuel delivery or ignition system issues rather than battery or starter problems.

The technician can gather appropriate tools and schedule the work based on the operational urgency.

7.2.3 Before/After Examples.

Before improvement initiative.

Asset: Air compressor. Problem: Not working right. Priority: Medium.

After training and process improvement.

Ø Asset: Workshop Air Compressor CAC-01.

Ø Problem: Compressor builds to 100 PSI then stops pressurising. System gradually loses pressure over 2-3 hours. No air leaks detected. Compressor motor runs continuously but no pressure increase. Started yesterday afternoon.

Ø Priority: High – impacts pneumatic tool operation across workshop, limiting production capacity. Reporter: Maintenance Tech Sarah Jones, ext 312.

The improved request provides actionable information that enables efficient response.

7.3 Avoiding Duplicate Requests.

Duplicate requests waste maintenance resources and corrupt work history data.

7.3.1 Why is checking for existing work orders important?

Before creating a new maintenance request, users should search for existing requests on the same asset.

Multiple people often notice the same problem independently, especially in multi-shift operations.

Creating duplicate requests causes:

1. Multiple technicians investigating the same issue.

2. Duplicate parts ordering.

3. Confusion about work status.

4. Inaccurate work history when duplicates are eventually merged or closed.

5. Frustrated requesters who see no response to their report when work is actually progressing under a different request number.

7.3.2 Types Of Waste And Issues Duplication Of Work Can Cause.

Duplicate maintenance work creates several waste categories:

1. Wasted investigation time: A technician spends 30 minutes diagnosing a problem already diagnosed by another technician responding to a different work order for the same issue.

2. Wasted parts: Parts are ordered against multiple work orders, creating excess inventory or emergency reorders when the first parts get used.

3. Wasted communication: Operators report the same problem to multiple people, maintenance supervisor fields questions about multiple work orders addressing the same issue, and planning staff attempt to schedule the same work multiple times.

4. Corrupted data: When duplicates are eventually discovered, one work order gets cancelled while another proceeds. Work history shows incomplete information because parts costs, labour hours and completion notes are split across multiple records. This corrupts reliability analysis and cost tracking.

5. Lost trust: When people report problems that appear to receive no response while duplicate work orders proceed unknown to them, they lose confidence in the maintenance system and may stop reporting issues.

6. Prevention requires discipline. Users should search before creating requests. Maintenance coordinators should review incoming requests for potential duplicates. CMMS platforms with good search functionality and mobile access make duplicate checking more practical.

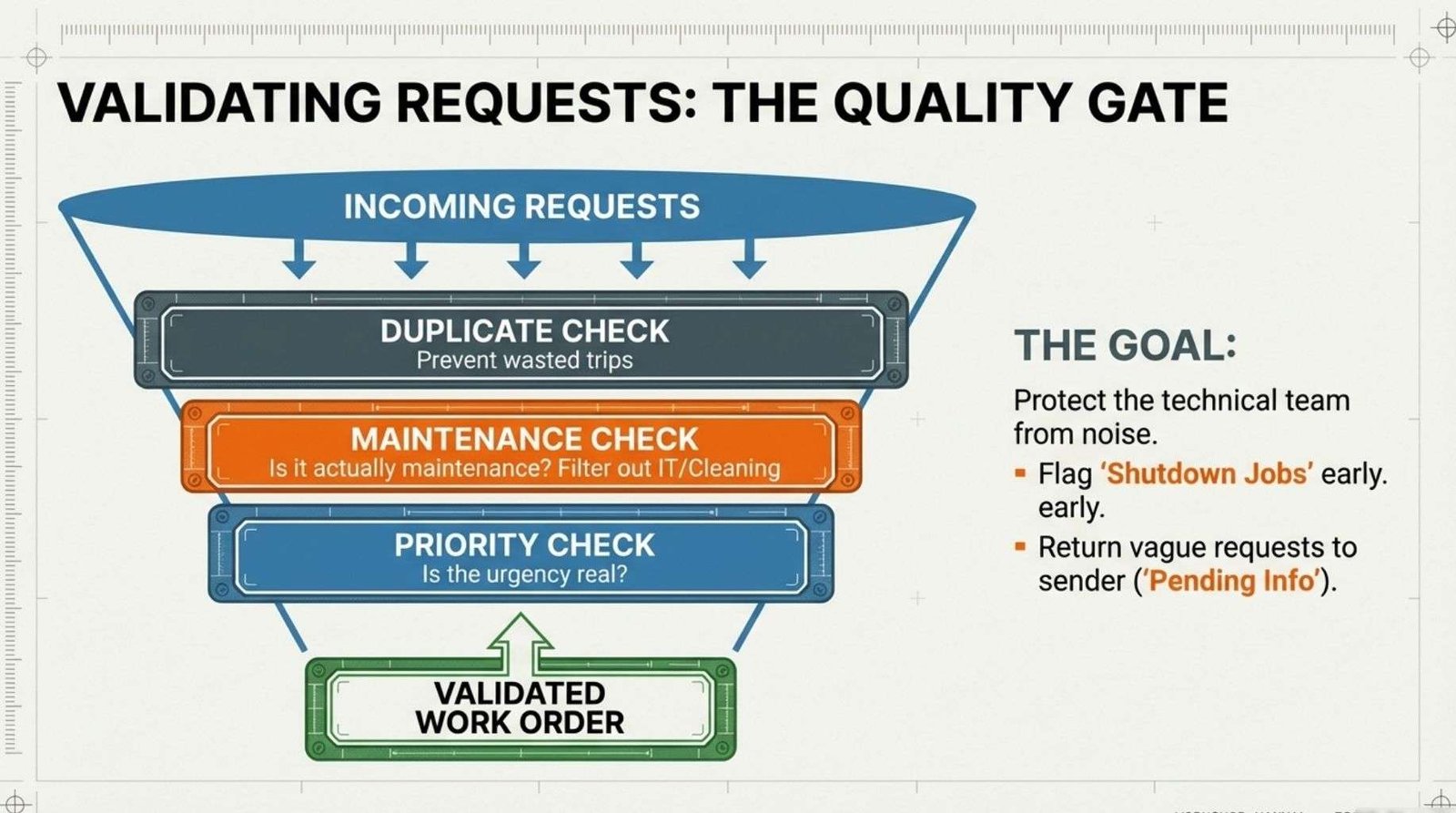

8.0 Validating Requests Before Work Begins.

Request validation represents a critical quality gate between problem identification and work execution. This step ensures maintenance resources address genuine needs using appropriate approaches.

8.1 Why Validation Matters.

Validation serves multiple purposes beyond simple quality checking.

8.1.1 Prevents Unnecessary Work.

Some reported problems resolve themselves, duplicate existing work orders or result from operational misunderstanding rather than equipment defects. Validation catches these situations before resources are committed.

A reported “pump failure” might actually be a closed isolation valve operated by someone unfamiliar with the system. A reported equipment malfunction might reflect operator training needs rather than mechanical problems. Validation identifies these situations and routes them appropriately.

8.1.2 Make Sure Modifications/Upgrades are not actioned without the necessary ‘change management’ request being approved.

Modifications, upgrades and configuration changes are not maintenance work. These activities require different approval processes, budgeting consideration and planning horizons.

Validation ensures these requests are identified and routed to appropriate change management processes. Allowing modifications to proceed as routine maintenance work creates several risks:

1. Technical risk: Changes made without engineering review may create safety hazards, violate codes or standards, void warranties or create incompatibilities with other systems.

2. Financial risk: Modifications may require capital budgeting rather than operational maintenance budgets. Bypassing proper financial controls creates accounting problems and distorts maintenance cost tracking.

3. Operational risk: Changes made without proper planning, testing and training may disrupt operations or create new problems. Production modifications should be scheduled during planned shutdowns rather than executed during normal operations.

A request to “upgrade the conveyor motor to higher horsepower for increased throughput” is not maintenance.

It is a modification requiring engineering assessment, capital approval, installation planning and operator training. Validation catches these requests and prevents inappropriate execution as routine work.

8.1.3 Is It Actually ‘Repairs And Maintenance’?

Repairs and maintenance restore assets to designed functional capability. Modifications change designed capability, configuration or performance.

This distinction matters legally, financially and operationally. Tax treatment may differ between repairs (operational expense) and improvements (capital expenditure). Insurance and warranty implications exist. Safety certification requirements may apply.

Maintenance work should not require new drawings, updated operating procedures or revised training programs. If these elements are needed, the work represents modification rather than maintenance.

8.1.4 Care Prior To Actioning Upgrades/Modificaitons Improvments.

Unapproved modifications can create cascading problems:

1. Safety hazards: Equipment modified without engineering review may operate outside safe parameters, creating risks to operators and maintenance personnel. Safety interlocks may be compromised. Load-bearing components may be overstressed.

2. Warranty voidance: Manufacturers typically void warranties when unauthorised modifications occur. A well-intentioned upgrade to improve performance may eliminate warranty coverage for the entire asset.

3. Regulatory violations: Modified equipment may no longer comply with relevant codes, standards or regulations. This creates liability exposure and may prevent legal operation.

4. Documentation corruption: Undocumented modifications create confusion for future maintenance, create safety risks when someone assumes original configuration and create problems during incident investigations when actual configuration does not match documentation.

5. System incompatibility: Modifying one component without considering system-level impacts may overload upstream or downstream equipment, create control system conflicts or affect process quality.

A maintenance technician who upgrades a pump motor to higher horsepower without engineering approval might overload the electrical circuit, exceed the coupling rating, create excessive vibration and void the pump warranty.

I think it’s fair to say that none of these risks would be apparent without proper change management review.

8.1.5 Ensuring Correct Classification.

Initial work classification by the requester represents their best assessment. Validation by maintenance personnel with broader system knowledge and diagnostic experience may reveal different classification.

What appears to be a breakdown to an operator may actually be a controls issue with the asset still functional.

What seems like minor corrective work may represent a symptom of more serious problems requiring urgent attention.

8.1.6 Has This Task Already Been Done?

In multi-shift operations, problems reported on one shift may be addressed by another shift before formal work orders are created or reviewed.

Validation prevents duplicate effort on already-completed work.

Time lag between request creation and validation means some problems resolve spontaneously, are addressed through workarounds or are fixed informally without documentation. Validation catches these situations.

8.1.7 Improving Planning Quality.

Validated requests provide reliable information for planning and scheduling. Planners can confidently develop detailed work plans, order parts and schedule labour knowing the work is genuine and properly characterised.

Unvalidated backlogs tend to create planning inefficiency.

Planners end up wasting time preparing for work that is no longer needed, misallocating resources to incorrectly classified problems or discovering missing information after work is scheduled.

8.2 What To Check.

Validation review addresses several key questions.

8.2.1 Is the Asset Number Assignment Correct?

Verify that the asset identified in the request matches the problem description and location. Asset selection errors are common, especially in facilities with multiple similar assets.

If the request describes a problem with “Workshop Air Compressor” but the asset selected is “Office Air Conditioner”, validation catches this error before work proceeds.

8.2.2 Is The Problem Description Clear?

Problem descriptions should provide sufficient information for planning and diagnostic preparation. Vague descriptions require follow-up with the requester.

A description reading “weird noise” needs clarification. What type of noise? Where does it originate? Is it constant or intermittent? Has it changed over time?

8.2.3 Is The Priority Designation Reasonable?

The assigned priority should reflect genuine operational urgency based on safety impact, production consequences and repair timeline considerations.

Validators with broader operational perspective may adjust priority up or down.

A problem marked “Critical” by an operator who is unaware that backup equipment is available may be downgraded. A problem marked “Low” by someone unaware of planned production increases next week may be upgraded.

8.2.4 Is It A Shutdown/Turnaround/Outage Event Job?

Some work cannot be performed safely or practically while equipment operates. This distinction affects scheduling dramatically.

Replacing pump seals typically requires equipment shutdown. Replacing motor bearings usually requires motor removal. Modifying control systems may require process shutdown.

Validators identify work requiring outage conditions and flag it appropriately. This enables coordination with production scheduling and grouping of outage-dependent work to minimise shutdown frequency and duration.

Work that requires shutdown but is not classified as such creates problems when technicians arrive to find equipment cannot be safely isolated for repair during normal operations.

8.2.5 Is More Information Needed?

Incomplete requests should be returned to the requester for additional detail rather than proceeding with inadequate information.

Common missing information includes:

1. Specific location when multiple similar assets exist.

2. Timeline of when the problem developed.

3. Whether the problem is continuous or intermittent.

4. Recent changes or work that might relate to the problem.

5. Operational impact if not immediately obvious.

Returning requests for more information may seem to slow the process, but it prevents wasted diagnostic time and false starts.

8.3 When To Reject Or Return a Request.

Not all requests should proceed as maintenance work orders. Several categories warrant rejection or redirection.

8.3.1 Non-maintenance Issues.

Some reported problems do not require maintenance work orders. Examples include:

1. Requests for consumable supplies (light bulbs, filters).

2. Operational questions or training needs.

3. Housekeeping issues.

4. IT support requests.

5. Facility service requests (catering, cleaning).

These items should be routed to appropriate departments rather than entering the maintenance backlog.

8.3.2 Duplicate Of An Existing Request Or Work Order.

When a request duplicates existing work, the duplicate should be closed with reference to the original.

The requester should be notified that work is already in progress.

Some organisations link duplicate requests to the original work order so all requesters receive notification when work completes.

8.3.3 The Task Has Already Been Completed.

Work completed informally or through other channels should have the request closed with completion notes explaining what was done.

This maintains work history accuracy.

Example: “Problem investigated, discovered isolation valve accidentally closed, valve reopened and equipment returned to normal operation, no repair work required”.

This documentation explains why no formal work order proceeded while confirming the issue was addressed.

8.3.4 Incomplete Information.

Requests lacking essential information should be returned to the requester with specific questions about what additional detail is needed.

The request status should indicate “Pending additional information” rather than remaining in the active backlog. This prevents the incomplete request from affecting workload metrics or scheduling processes.

8.3.5 Improvement/Upgrade/Modification Tasks Disguised As Maintenance.

These should be redirected to change management processes with explanation. The requester should understand why the change management path is necessary rather than feeling the request was simply rejected.

Example response: “This request to increase conveyor speed represents a modification requiring engineering review and capital approval. I have forwarded your suggestion to the facilities manager for evaluation through the capital planning process. Thank you for identifying this improvement opportunity”.

This response acknowledges the value of the suggestion while explaining why it cannot proceed as routine maintenance.

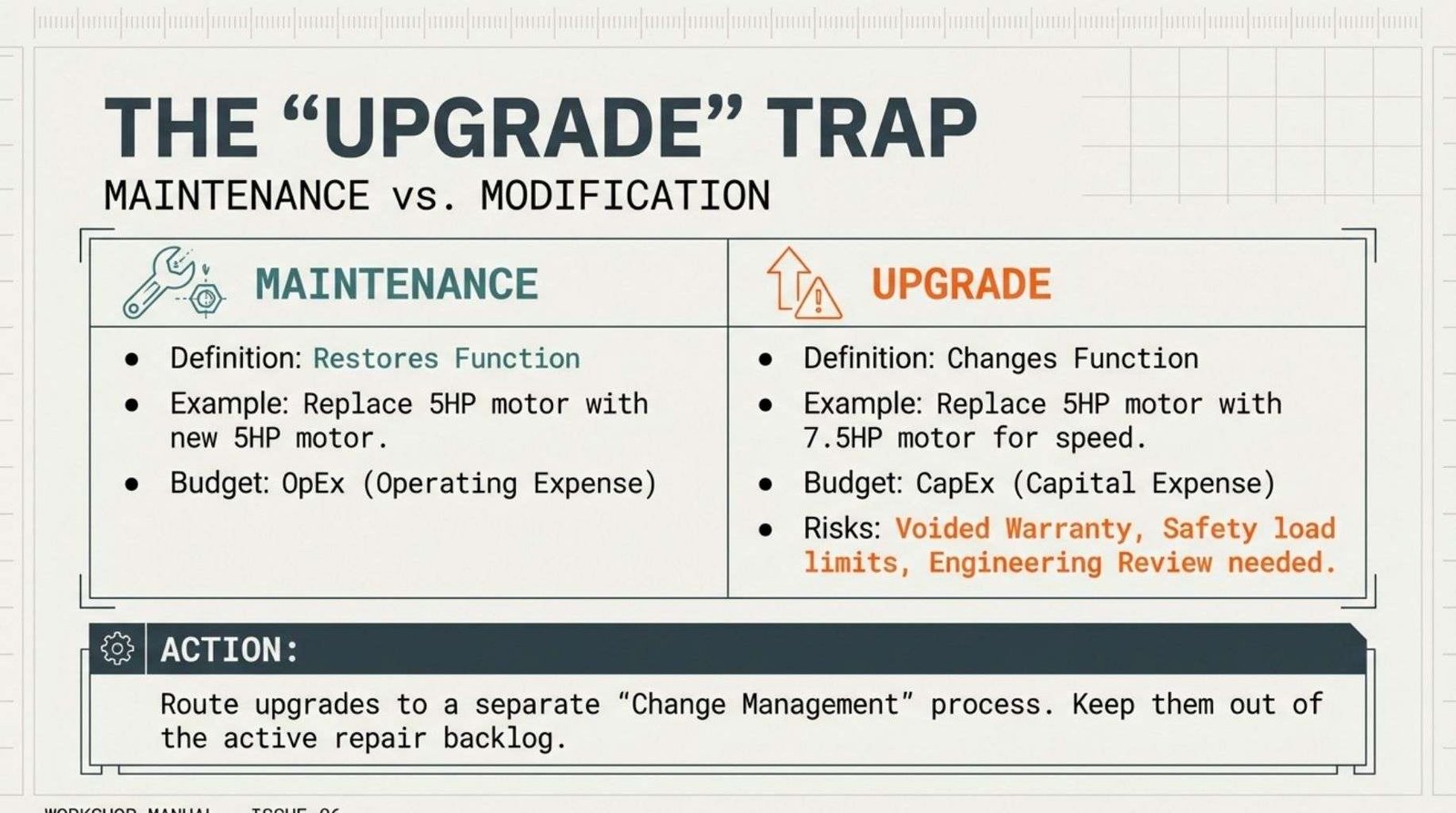

9.0 Identifying Improvement/Upgrade/Modification Tasks.

Maintaining clear boundaries between maintenance work and improvement work protects both processes from contamination.

9.1 What Counts As Improvement Work?

Improvement work changes asset capability, performance or configuration beyond restoring original design function.

Changes to capability, performance or configuration good examples of this and they include:

1. Increasing equipment capacity or throughput.

2. Adding new features or functions.

3. Changing control logic or setpoints.

4. Reconfiguring system layouts.

5. Upgrading to newer technology.

6. Modifying safety systems.

7. Changing operating parameters.

A request to “replace the 5HP motor with a 7.5HP motor” is improvement work even if the current motor is failing.

The appropriate maintenance response is replacing the failed 5HP motor with an equivalent 5HP unit. The capacity increase represents a separate improvement decision.

9.2 Why It Should Not Be Logged as Corrective or Breakdown.

Mixing improvement work with maintenance work corrupts both processes.

9.2.1 Different Approval Path.

Improvements require evaluation of:

1. Technical feasibility and safety.

2. Return on investment.

3. Budget availability.

4. Strategic alignment.

5. Timing relative to other projects.

These considerations differ fundamentally from maintenance decisions, which focus on restoring function to maintain existing capability.

9.2.2 Different Budgeting.

Maintenance work typically falls under operational budgets with established allocation for routine repairs, parts and labour.

Improvement work often requires capital budgets with different approval thresholds, funding sources and timing cycles.

Allowing improvements to consume maintenance budgets creates two problems. Maintenance budget depletes for non-maintenance purposes, preventing adequate coverage of legitimate repair needs. Improvement work proceeds without proper capital planning and financial controls.

9.2.3 Different Planning Horizon.

Maintenance work generally proceeds within weeks or months once identified. Improvement work may queue for months or years depending on priorities, budgets and resource availability.

Mixing these categories creates confusion about expected timelines and distorts maintenance backlog metrics. A maintenance backlog containing numerous improvement ideas appears much larger and older than reality warrants.

9.3 Capturing Improvement/Upgrade/Modification Ideas.

Improvement ideas have value and should be captured for future consideration. The goal is capturing them without contaminating the maintenance work process.

9.3.1 Use A Separate Category Or Tag.

Many CMMS platforms support custom fields, tags or categories.

Creating an “Improvement Idea” category enables capture within the same system while maintaining separation from maintenance work.

When a request is identified as improvement work during validation, it is recategorised and routed appropriately. This maintains the suggestion in the system while removing it from the maintenance backlog.

9.3.2 Keep Them Out Of The Maintenance Backlog/Forward Log.

Improvement items should be visible to management for evaluation but invisible to maintenance planners and schedulers. This prevents them from affecting maintenance workload metrics and resource allocation.

Some organisations maintain separate “Improvement Register” databases outside the CMMS. Others use CMMS functionality but with filters that exclude improvement items from maintenance reports.

The specific approach matters less than maintaining clear separation. Maintenance teams should not plan or schedule improvement work through normal maintenance processes.

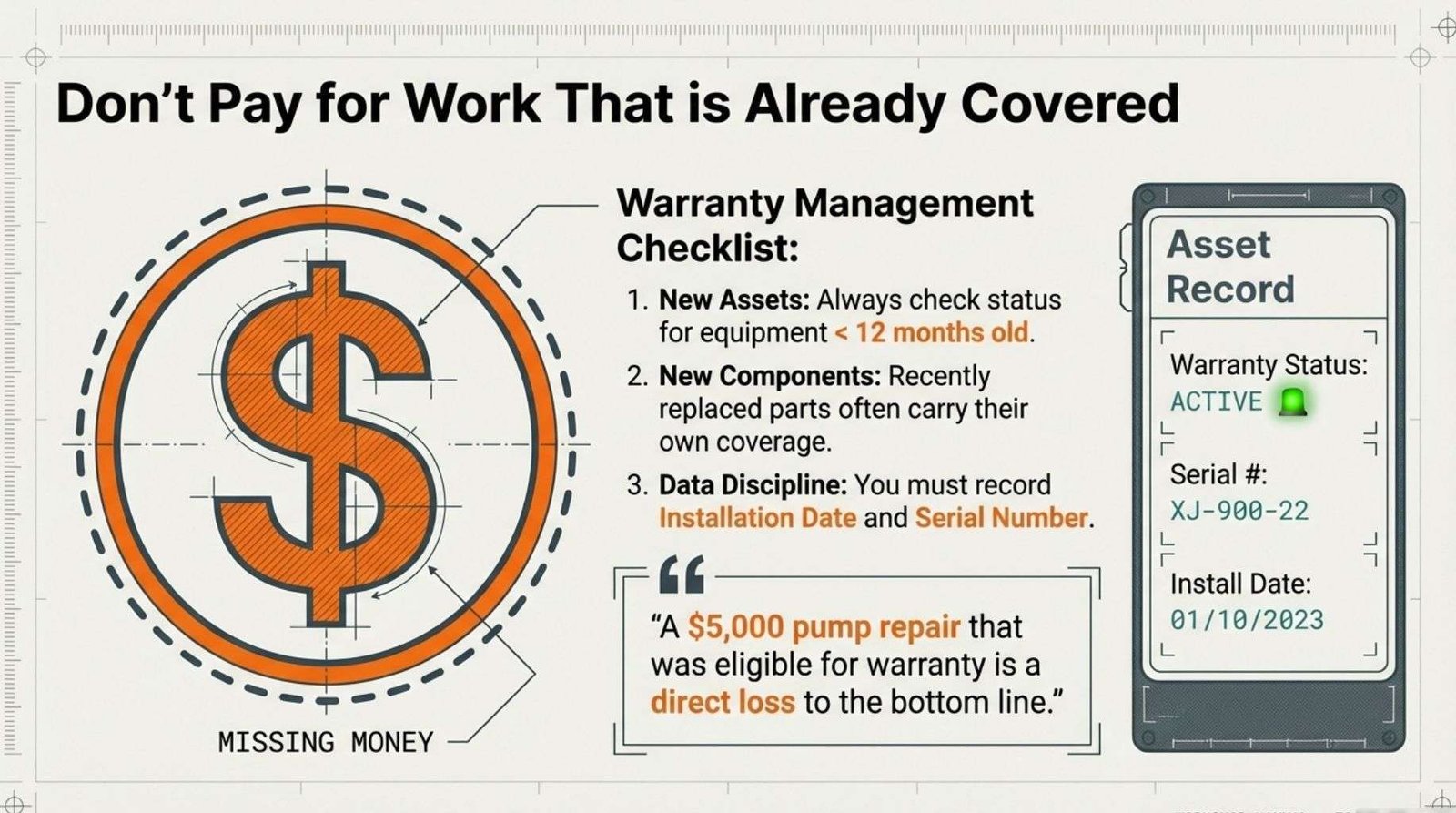

10. Warranty Considerations For Small Businesses.

Warranty tracking protects maintenance budgets by ensuring manufacturers and suppliers bear appropriate repair costs during warranty periods.

10.1 When to Check Warranty.

The short answer is to, “Always check if something is under warranty.”

It’s not a lot of effort for something that could result in a lot of gain.

Certain situations warrant immediate warranty status checks before proceeding with repair work.

New Assets/Equipment.

All work on equipment less than 12 months old should trigger warranty review. Most manufacturing defects appear during early operational life.

Recently Replaced Components.

Component replacements typically include warranty coverage from the supplier. Work on recently replaced parts should include warranty status verification.

Protect Your Maintenance Budget.

Warranty coverage represents pre-paid repair services. Failing to utilize valid warranties wastes this value and expends maintenance budget unnecessarily.

Common causes of missed warranty claims include:

1. Lack Of Tracking: Without systematic warranty tracking, staff may not know equipment is under warranty when failures occur. A CMMS without warranty date fields or alerts provides no visibility to warranty status.

2. Urgency Bias: When equipment fails, the immediate focus on restoring operation may overshadow warranty considerations. Technicians proceed with repairs before checking warranty status.

3. Process Gaps: Even when warranty status is known, some organisations lack clear processes for filing claims, coordinating with vendors and ensuring warranty work is performed to standards.

4. Documentation Deficiency: Warranty claims require documentation proving the defect occurred during the warranty period and resulted from manufacturing issues rather than misuse. Without good work history records, claims may fail.

A small manufacturer that spends $5,000 repairing a pump that failed during its warranty period has wasted $5,000 that should have been recovered from the supplier. If this occurs across multiple failures throughout the year, the cumulative waste becomes substantial.

Proper warranty tracking and claim processes transform warranties from theoretical coverage to actual budget protection.

10.2 What Information Should You Record?

Effective warranty tracking requires specific information in the CMMS.

10.2.1 Dates.

Warranty start and end dates enable automatic identification of warranty-eligible equipment. Start dates typically match installation or commissioning dates rather than purchase dates.

Some warranties include graduated coverage (full replacement first year, partial coverage second year). Recording coverage details enables appropriate claim timing decisions.

10.2.2 Serial Numbers/VIN Numbers.

Warranty claims require proof that specific equipment is covered. Serial numbers provide this link between the asset and manufacturer records.

Recording serial numbers during equipment installation ensures this information is available when needed rather than requiring emergency searches through paperwork when failures occur.

10.2.3 Supplier Details.

Warranty claims require knowing who provides coverage.

For equipment with multiple components from different suppliers, tracking which supplier warranties which components matters.

Complete supplier information includes:

1. Company name.

2. Contact person.

3. Phone and email.

4. Warranty claim submission process.

5. Any specific claim requirements.

10.3 How Do You Track Warranty Work?

Even simple CMMS platforms can support warranty tracking with appropriate setup.

10.3.1 Tags.

Custom tags like “Warranty-Active” enable quick identification of equipment under warranty. Reports filtering for this tag show all current warranty-covered assets.

Tags should be date-based so they can be added at installation and removed when warranty expires.

10.3.2 Populate All Warranty Information In The Applicable Module.

If the CMMS includes dedicated warranty fields, use them consistently. Common fields include:

1. Warranty start date.

2. Warranty end date.

3. Warranty provider.

4. Warranty terms.

5. Serial number.

Complete population of these fields enables automated reporting and alerts.

10.3.3 Notes.

Some warranty terms include specific conditions or exclusions. Recording these in asset notes ensures staff understand any limitations.

Example note: “5-year motor warranty excludes coverage if operated above nameplate ratings or in contaminated environments. Must maintain proper lubrication per manufacturer schedule to maintain warranty validity”.

10.3.4 Attachments.

Warranty documents should be attached to asset records in the CMMS.

This provides instant access to terms, claim procedures and supplier contact information when failures occur.

Digital copies of warranty certificates, installation records and manufacturer correspondence belong in the CMMS attached to relevant asset records.

10.3.5 Third Party Warranty Software Products.

Businesses with extensive warranty-covered equipment may benefit from dedicated warranty management software. These specialized tools provide features like:

1. Automated warranty expiration alerts.

2. Claim workflow management.

3. Supplier performance tracking.

4. Recovery cost tracking.

5. Multi-tier warranty management.

Integration with the CMMS enables seamless flow of information between systems. When a maintenance request is created for warranty-covered equipment, the warranty system flags it automatically.

Third-party warranty solutions add cost but may pay for themselves through improved claim rates and reduced administrative burden.

The decision depends on the volume and value of warranty-covered assets.

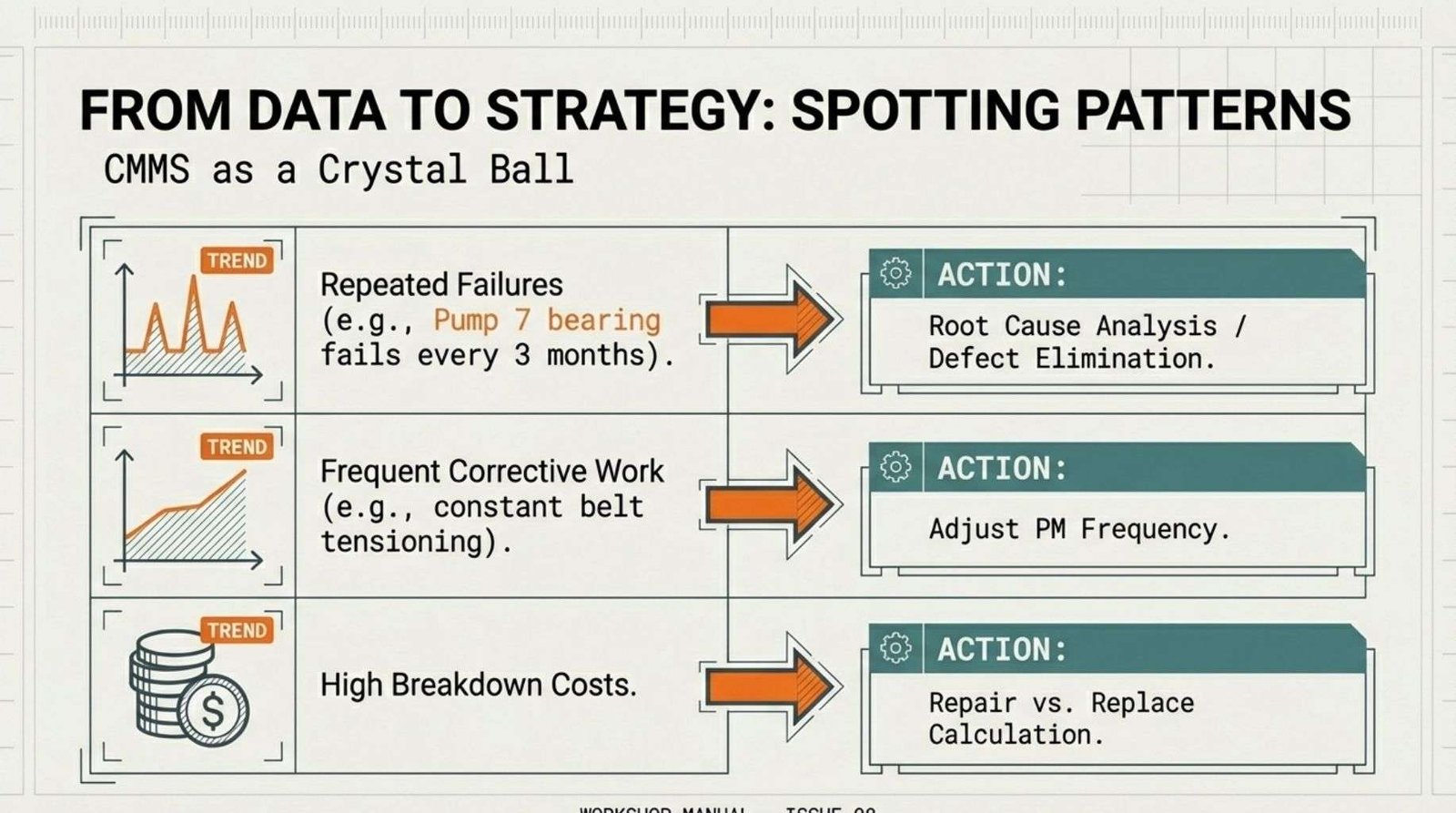

11.0 Correct Classification Can Improve Your Maintenance Strategy.

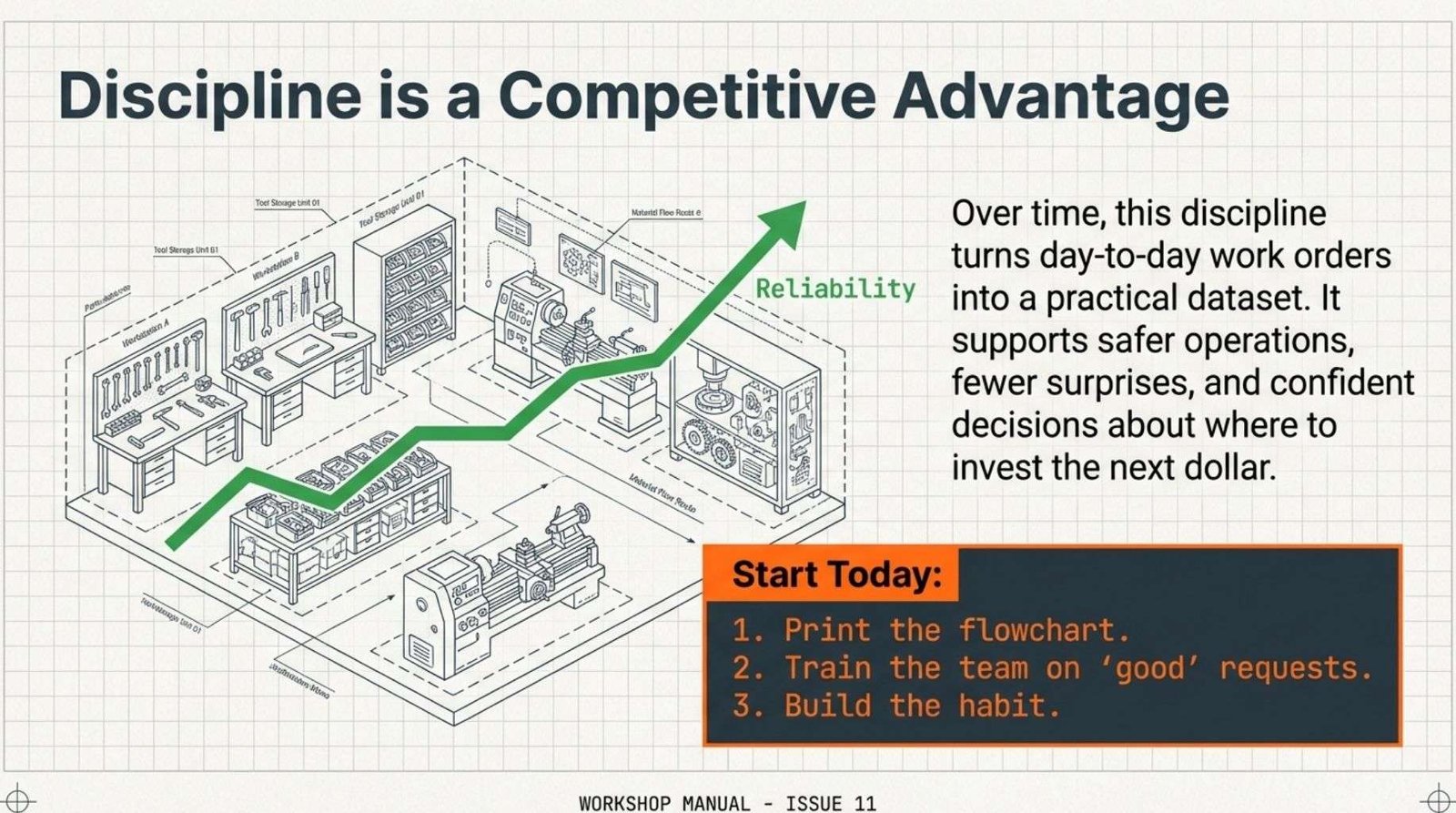

Consistent, accurate work classification creates data that drives maintenance strategy improvement. The benefits accumulate over time as the dataset grows.

11.1 Spotting Patterns.

Classified work history reveals patterns invisible in day-to-day operations.

11.1.1 Repeated Failures.

When the same asset experiences multiple breakdown work orders for similar problems, a pattern becomes apparent and this may indicate:

1. Inadequate repair quality.

2. Inappropriate parts selection.

3. Operating conditions exceeding design parameters.

4. Maintenance procedure deficiencies.

5. Training needs.

Example: Pump 7 work history shows bearing replacement every 3-4 months while similar pumps operate for 18-24 months between bearing changes.

Investigation might reveal misalignment, contamination issues or operating speed problems specific to this installation.

11.1.2 Common Corrective Tasks.

Frequent corrective work of the same type across multiple assets suggests opportunities for preventive maintenance program development.

Example: Monthly work history shows multiple corrective work orders for “belt tension adjustment” across various equipment.

This pattern suggests adding belt tension inspection to the preventive maintenance program would catch issues during routine checks rather than requiring separate corrective work orders.

11.1.3 Assets With High Breakdown Rates.

Some assets consume disproportionate maintenance resources. Quantifying this reality through classified work history supports replacement decisions.

Example:

Let’s say that the work history analysis shows that Forklift FL-02 has consumed $X,000 in breakdown maintenance over the past year, averaging one breakdown per month.

If this expenditure covers 60% of a replacement forklift cost and would eliminate the operational disruptions and safety concerns associated with frequent failures, then that should spark some discussions in The Economics Of Repair Vs Replacement space.

This is about deciding whether it is financially smarter to keep repairing an asset or to replace it entirely.

The decision is typically driven by comparing:

1. Cost of the repair.

1. Parts.

2. Labour.

3. Downtime cost.

4. Risk of repeat failure.

2. Remaining useful life of the asset.

1. How much life is left after the repair.

2. Whether the repair restores full reliability or only delays the next failure.

3. Cost of replacement.

1. Purchase price.

2. Installation and commissioning.

3. Training or integration.

4. Any improvements in efficiency, safety, or reliability.

4. Total cost of ownership (TCO).

This includes:

1. Energy use.

2. Consumables.

3. Reliability.

4. Maintenance burden.

5. Expected future failures.

The decision is essentially: “Does repairing this asset give us enough remaining value to justify the cost, or is replacement the more economical long‑term choice?”

11.2 Feeding Insights Back Into The Maintenance Strategy.

Data analysis should drive maintenance program adjustments.

11.2.1 Adjusting Inspection Frequency.

Assets with frequent corrective work orders might benefit from more frequent inspections to catch problems earlier. Assets with no findings during inspections might allow reduced inspection frequency.

Example: Compressor CAC-01 history shows that 80% of breakdown work orders were preceded by temperature anomalies noted in weekly inspections. Increasing inspection frequency to twice weekly for this compressor enables earlier intervention.

11.2.2 Updating Checklists.

Recurring problems that were not detected during inspections indicate checklist gaps.

Example: Multiple conveyor belt failures occurred without advance warning despite weekly inspections. Investigation reveals that checklist items focused on belt tension and tracking but did not include belt edge condition inspection. Adding belt edge inspection to the checklist addresses this gap.

11.2.3 Replacing Unreliable Components.

When specific components fail repeatedly, exploring alternative suppliers or specifications may improve reliability.

Example: Work history shows that Brand X motor contactors average 8 months before failure while Brand Y contactors on similar applications average 3 years.

Standardising on Brand Y contactors reduces maintenance burden and improves reliability despite potentially higher unit cost.

11.2.4 Training Opportunities.

Patterns in operator-reported problems may reveal training needs.

Example: Multiple work requests for “machine jammed” occur across different operators on the same equipment.

Investigation reveals that the jam results from improper material loading technique. Additional operator training eliminates these false work requests.