Maintenance Leader Development

A company’s long‑term success depends not only on the quality of its equipment or the sophistication of its systems, but on its ability to consistently develop exceptional leaders.

In maintenance environments, where reliability, safety and operational continuity are non‑negotiable, the need for strong leadership is even more pronounced.

As individuals progress through the organisational structure, their responsibilities expand far beyond their own technical tasks.

They become accountable for the performance of teams, the stewardship of assets and the overall stability of operations.

This shift requires a deliberate transformation: from being a skilled individual contributor to becoming a leader capable of influencing culture, strategy and long‑term outcomes.

Maintenance leaders must navigate a complex landscape that blends technical expertise, human leadership, financial awareness and regulatory understanding.

They must ensure the smooth operation of the company’s assets, support the wellbeing and development of employees and uphold standards in areas such as company law, safety and compliance.

To lead effectively, they need a broad and integrated skill set, one that evolves over time and is strengthened through structured development pathways.

At the heart of maintenance leadership are several core competencies that define high performance and long‑term organisational value.

Frontline Leadership and Management.

The transition from technician to leader is one of the most challenging steps in a maintenance career.

It requires a shift from doing the work to enabling others to do it well. Effective frontline leaders must be able to coordinate teams, manage daily workflows and maintain clarity in fast‑moving operational environments.

They must communicate expectations clearly, delegate tasks appropriately and motivate team members to achieve shared goals.

This is where leadership becomes more than authority, it becomes influence.

Leaders must build trust, demonstrate fairness and create an environment where people feel supported, respected and accountable.

Strong frontline leadership also involves understanding human behaviour. Leaders must recognise the different personalities, strengths and motivations within their teams.

They must be able to guide individuals through change, manage conflict constructively and foster a sense of shared purpose.

When frontline leaders excel, they create stability, reduce operational friction and set the tone for a high‑performance culture.

Deep Technical and Operational Acumen.

Credibility in maintenance leadership is built on technical understanding.

Leaders must be well‑versed in the machinery, equipment and operational processes that define their organisation.

This includes knowledge of maintenance strategies, predictive, preventive and corrective and the ability to interpret data from modern monitoring systems.

Technical acumen allows leaders to make informed decisions, mentor their teams effectively and evaluate the risks and benefits of different maintenance approaches.

However, technical expertise alone is not enough. Leaders must also understand how maintenance activities influence production, quality and long‑term asset health. They must be able to balance short‑term operational pressures with long‑term reliability goals.

This broader operational awareness enables leaders to prioritise effectively, allocate resources wisely and advocate for maintenance needs at higher levels of the organisation.

Uncompromising Safety Advocacy.

Safety is not a box to tick, it is a culture to uphold. Maintenance leaders play a critical role in shaping that culture.

They must model safe behaviours, reinforce safe work practices and ensure that every team member understands the importance of risk identification and mitigation. This requires more than compliance with procedures; it requires genuine commitment.

Leaders must create an environment where people feel empowered to speak up, stop work when necessary and challenge unsafe conditions.

They must ensure that training is ongoing, relevant and practical. When leaders champion safety consistently, they reduce incidents, protect their teams and strengthen the organisation’s reputation and operational resilience.

Financial and Resource Stewardship.

Modern maintenance leaders are not just technical experts, they are business managers. They must understand budgets, cost control and the financial implications of maintenance decisions.

This includes analysing expenditure, forecasting resource needs and justifying investments in tools, technology, or asset upgrades.

Leaders must be able to link maintenance activities to financial outcomes, demonstrating how reliability improvements reduce downtime, increase productivity and extend asset life.

Financial stewardship also involves understanding life‑cycle costs, evaluating return on investment and making decisions that balance immediate operational needs with long‑term value.

When leaders manage resources effectively, they contribute directly to the organisation’s profitability and strategic stability.

High‑Performance Team Development.

A leader’s greatest impact is not in what they achieve personally, but in what they enable their team to achieve.

High‑performance maintenance teams do not emerge by accident, they are built through deliberate coaching, constructive feedback and consistent support.

Leaders must identify skill gaps, provide development opportunities and create pathways for career progression. They must also cultivate a collaborative environment where team members feel valued and empowered.

Effective leaders understand that engagement drives performance. They recognise achievements, address issues early and maintain open communication.

They build a culture of accountability where expectations are clear and individuals take ownership of their work. When leaders invest in their teams, they create a multiplier effect that strengthens the entire organisation.

Systematic Problem‑Solving and Continuous Improvement.

Maintenance leadership requires the ability to diagnose and resolve complex problems. Leaders must be skilled in structured problem‑solving methods such as Root Cause Analysis and Failure Mode and Effects Analysis.

They must be able to identify patterns, evaluate data and implement solutions that address underlying causes rather than symptoms.

Beyond problem‑solving, leaders must champion continuous improvement.

This involves promoting Lean principles, eliminating waste and encouraging innovation. Leaders must create a mindset where improvement is ongoing, not reactive.

When continuous improvement becomes part of the culture, reliability increases, costs decrease and operational performance becomes more predictable.

Developing Future Leaders.

Leadership development is not a one‑time event, it is a continuous journey. Organisations must create structured learning pathways that allow emerging leaders to build the skills they need progressively.

This includes formal training, mentoring, coaching and real‑world application.

As individuals develop, they should be given opportunities to lead small projects, manage budgets, facilitate safety reviews, or coordinate shutdown activities.

These experiences build confidence, reinforce learning and demonstrate readiness for greater responsibility.

By investing in leadership development, organisations create a sustainable pipeline of capable leaders who can uphold standards, drive improvement and support long‑term success.

Maintenance leadership is not just about managing today’s operations, it is about shaping the future of the organisation.

The Relationship Landscape of a Maintenance Leader.

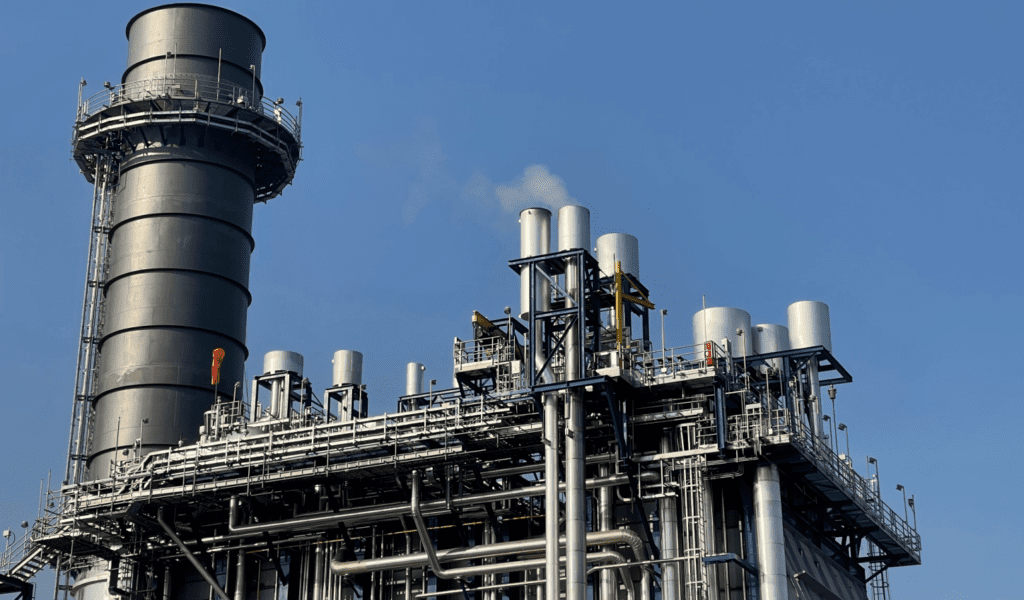

Maintenance leaders in Australian gold mining operations operate at the centre of a dense web of internal and external relationships.

Their effectiveness depends not only on technical competence but on their ability to communicate, negotiate, influence and collaborate across diverse groups.

The table below illustrates the range of stakeholders a maintenance leader may interact with on any given day, along with the skills required to manage each relationship effectively.

| Stakeholder Group |

Typical Interactions |

Skills Required |

| Maintenance Technicians |

Daily direction, coaching, task prioritisation, safety checks |

Leadership communication, coaching, technical mentoring |

| Production Supervisors |

Coordinating shutdowns, negotiating access to equipment, aligning priorities |

Negotiation, conflict resolution, operational awareness |

| Planners & Schedulers |

Work management, backlog review, resource allocation |

Planning literacy, analytical thinking, collaboration |

| Health & Safety Teams |

Incident reviews, risk assessments, safety audits |

Risk management, compliance knowledge, safety leadership |

| Supply & Procurement |

Ordering parts, managing lead times, evaluating suppliers |

Commercial awareness, cost control, relationship management |

| External Contractors |

Supervising work quality, ensuring compliance, managing performance |

Contract management, assertiveness, quality assurance |

| OEM Representatives |

Technical support, warranty claims, equipment upgrades |

Technical negotiation, diagnostic reasoning, strategic communication |

| Environmental & Compliance Teams |

Ensuring maintenance activities meet regulatory standards |

Regulatory understanding, documentation accuracy |

| Senior Leadership |

Reporting performance, justifying budgets, presenting improvement plans |

Strategic thinking, financial literacy, executive communication |

| HR & Training |

Workforce planning, performance management, training needs analysis |

People development, empathy, structured feedback |

| Community & Indigenous Liaison Teams |

Supporting local employment initiatives, ensuring cultural respect |

Cultural awareness, stakeholder sensitivity |

This relationship ecosystem highlights a critical truth: maintenance leadership is not a technical role with some people responsibilities, it is a people role built on a foundation of technical credibility.

The ability to navigate these interactions with clarity, confidence and emotional intelligence directly influences asset reliability, team morale and operational performance.

Why Succession Planning for Maintenance Leaders Matters.

Succession planning is often misunderstood as a “nice to have” administrative exercise. In mining, especially in remote or high‑pressure environments like Australian gold operations, it is a strategic necessity.

Maintenance leaders carry enormous responsibility: asset reliability, safety culture, cost control, workforce stability and cross‑departmental coordination all depend on their capability and presence.

When that leader is suddenly unavailable, the ripple effects can be immediate and costly.

Protecting the Business.

A well‑prepared successor ensures continuity in:

- Safety leadership, avoiding lapses in supervision, risk management and procedural compliance

- Work management, preventing backlog blowouts, scheduling chaos and reactive firefighting

- Cost control, maintaining discipline around budgets, procurement and contractor management

- Team stability, avoiding uncertainty, disengagement, or conflict during leadership gaps

A lot of mining operations run 24/7. Equipment doesn’t stop breaking down or needing preventive maintenance because a leader is sick, on leave, or has resigned.

Without a ready successor, the organisation is exposed to operational, financial and safety risks.

Protecting the Leader.

Succession planning is not just good for the business, it is essential for the wellbeing and sustainability of the leader themselves.

A maintenance leader with no trained backup becomes:

- The default responder for every issue.

- Unable to take meaningful leave.

- At risk of burnout.

- Reluctant to pursue promotions or new opportunities.

- Trapped in a role that depends entirely on their presence.

By contrast, a leader with a capable second‑in‑charge gains:

- Freedom to take leave without guilt or operational disruption.

- Reduced stress knowing the team can function without them.

- Career mobility because someone can step up when they move on.

- A stronger team built on shared responsibility and capability.

Succession planning is an act of leadership maturity.

It signals that the leader is building a system that can thrive without them , the ultimate test of effective leadership.

Protecting the Future.

Mining operations face ongoing workforce challenges: ageing tradespeople, competition for skilled labour and the need for increasingly sophisticated technical and digital skills.

Developing future leaders is not optional; it is a strategic investment in organisational resilience.

A strong succession pipeline ensures:

- Continuity of culture

- Preservation of institutional knowledge

- Faster onboarding of new leaders

- Reduced recruitment costs

- Greater internal mobility and retention

In short, succession planning ensures that leadership capability is not left to chance.