Broken Window Theory And CMMS Master Data

Disclaimer.

This article is provided for educational and professional development purposes.

It draws on established asset management principles, behavioural science, and industry practice.

It does not constitute legal, financial, engineering, or organizational advice.

The views, opinions, and interpretations expressed are solely those of the author.

Every organization operates within its own regulatory, cultural, and operational context.

Readers should assess the concepts presented here in alignment with their internal governance frameworks, risk tolerances and data management policies.

Top 5 Takeaways.

1. Small defects are not small, they are signals. Whether in a city, a factory, or a CMMS, visible disorder teaches people what level of care is acceptable.

2. Data quality is not clerical, it is cultural. Every incomplete field, duplicate work order, or ghost asset erodes trust and shapes user behaviour.

3. Excellence is binary. Buker Business Excellence aligns perfectly with Broken Window Theory: a record is either correct (✓) or it is a broken window (✕).

4. Zero tolerance is the only sustainable strategy. Fixing defects within 24 hours, enforcing standards and maintaining visible stewardship prevents digital decay.

5. AI will transform CMMS governance. Automated detection, recommendations and self‑healing corrections will make data quality faster, safer and more scalable than ever.

Article Summary.

In 1982, James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling articulated the Broken Window Theory, a behavioural framework that has strongly influenced urban management and public policy.

Its insight was simple but profound: visible signs of disorder invite further disorder. A single broken window left unrepaired signals that no one cares and, once that perception takes root, decay accelerates.

This principle was famously operationalized in New York City’s 1990s reforms, where leaders enforced a radical standard: fix every visible defect as quickly as possible. Slashed subway seats were mended overnight, graffiti was removed before commuters saw it twice and vandalized signs were repaired within hours.

The city demonstrated that the speed of correction can matter more than the size of the defect, and many observers linked this discipline to broader improvements in safety and public confidence.

Industry soon recognized the same pattern. Behavioural‑Based Safety, 5S and TPM all rest on the idea that small deviations shape culture and, if tolerated, normalize larger failures.

In a similar vein, Buker Business Excellence reinforces this with a binary standard: a process is either 100% correct (✓) or it is not (✕) — a “broken window” in operational form.

There is no in‑between; anything less invites disorder.

Today, the same psychology governs digital environments. In maintenance and asset‑intensive industries, the CMMS has become the operational nervous system and, like any neighbourhood, it develops its own broken windows: duplicate work orders, ghost assets, inconsistent naming, incomplete PMs and inaccurate master data. Each defect erodes trust.

Users create workarounds, maintain shadow spreadsheets and gradually abandon the system. Data decay spreads exponentially, inflating backlog, distorting KPIs, increasing risk and driving up cost.

The answer is zero tolerance for data disorder: rapid correction, visible stewardship, micro‑audits, disciplined project integration and strict control of asset lifecycle transitions.

Emerging AI capabilities will accelerate this transformation by detecting defects in real time, proposing targeted corrections and enabling safe, partially automated remediation.

Broken Window Theory is not fundamentally about crime or buildings; it is about human behaviour and how people interpret signals of care and control.

In our current and constantly evolving digital era, CMMS master data is the new neighbourhood. Keep it clean and everything works better.

Allow it to decay and organizational decline becomes inevitable.

Table of Contents.

1.0 The Foundation: How Broken Window Theory Was Born

- 1.1 Wilson & Kelling’s Original Insight

- 1.2 The Abandoned Factory Story

- 1.3 The Revelation: It Wasn’t One Big Crime, It Was Hundreds of Small Ones

- 1.4 The Counterfactual: What If the First Window Had Been Replaced?

- 1.5 The New York Experiment: Fix Everything, No Exceptions

- 1.6 The Psychology of Visible Disorder

2.0 The Evolution: From Crime Prevention to Industrial Safety

- 2.1 New York City’s Broken Windows Experiment

- 2.2 Slashed Seats, Graffiti‑Etched Windows and the 24‑Hour Rule

- 2.3 Behavioural‑Based Safety (BBS)

- 2.4 5S and the Japanese Manufacturing Interpretation

- 2.5 The Universal Principle: Order Maintained = Behaviour Elevated

3.0 Buker Business Excellence: The Operational Standard Behind “Broken Windows”

- 3.1 Why Psychology Needs Standards

- 3.2 The Binary Model: Green Ticks and Red Crosses

- 3.3 How Buker Defines a “Broken Window” in Business

- 3.4 The Triple Bottom Line (TBL) Lens

- 3.5 Why 95% Accuracy Is Still Failure

- 3.6 The Bridge to CMMS: Red Crosses in Master Data

4.0 The Bridge: Why CMMS Master Data Is the New “Neighbourhood”

- 4.1 Data as Digital Infrastructure

- 4.2 What a “Broken Window” Looks Like in a CMMS

- 4.3 How Users Interpret Data Defects

- 4.4 The Cascade: From First Defect to System Abandonment

5.0 Why Data Decay Is Dangerous

- 5.1 The Trust Erosion Cycle

- 5.2 The Operational Consequences

- 5.3 The Compounding Effect of Data Defects

- 5.4 The 10x–25x Cost Multiplier of Delayed Correction

6.0 The Solution: Zero Tolerance for Data Disorder

- 6.1 The Core Philosophy

- 6.2 The 24‑Hour Rule

- 6.3 Data Stewards: The Digital Neighbourhood Watch

- 6.4 Micro‑Audits and Quality Routines

- 6.5 Building a Culture of Precision

- 6.6 The First 90 Days

- 6.7 Technology Enablers

7.0 Conclusion: A Thousand Broken Windows

- 7.1 The Psychology of Care

- 7.2 The CMMS as a Living Environment

- 7.3 The Long‑Term Payoff of Zero Tolerance

- 7.4 The Call to Action

8.0 Appendices

- 8.1 CMMS Broken Window Checklist

- 8.2 Sample Data Steward Role Description

- 8.3 30‑Day, 60‑Day, 90‑Day Implementation Plan

- 8.4 Micro‑Audit Templates

- 8.5 AI‑Enabled CMMS Governance and Automated Data Stewardship

9.0 Bibliography.

1.0 The Foundation: How Broken Window Theory Was Born.

Broken Window Theory stands as one of the most enduring behavioural frameworks of the modern era, influencing urban policy, industrial safety, manufacturing excellence and now digital asset management.

Its power lies not in abstract philosophy but in observable human responses to environmental signals, a principle that translates seamlessly to CMMS master data governance.

To understand why, we must return to the theory’s origins, the stories that shaped it and the psychology that makes it universally applicable.

1.1 Wilson & Kelling’s Original Insight.

In March 1982, social scientists James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling published “Broken Windows: The Police and Neighbourhood Safety” in The Atlantic Monthly.

Their argument challenged the dominant criminology of the time: major crimes do not emerge from nowhere, they grow out of environments where minor disorders are tolerated.

A broken window left unrepaired broadcasts a potent message:

- “Nobody is watching.”

- “Nobody cares.”

- “Standards are optional here.”

This environmental cue reshapes social norms, granting subconscious permission for further decay.

Wilson and Kelling emphasized that policing should prioritize order maintenance, not just reactive crime‑fighting.

Their insight marked a paradigm shift: preventing the cascade of disorder required addressing visible signals immediately, before they normalized neglect.

1.2 The Abandoned Factory Story: The Perfect Illustration.

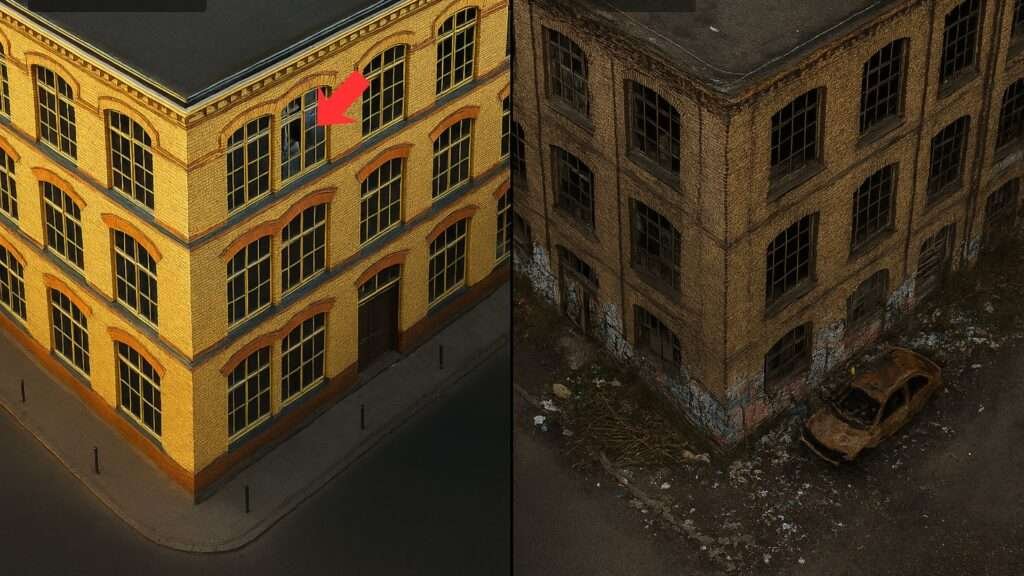

To crystallize their theory, Wilson and Kelling often referenced a vivid parable: the abandoned textile factory.

Imagine a once‑thriving brick edifice in a prosperous neighbourhood, windows intact, doors secure, signs polished.

Then, one pane cracks. No one fixes it. Soon, another shatters. Graffiti appears on the wall. A door hangs ajar after a casual kick.

Rubbish accumulates inside. Lights smash. Before long, the structure crumbles not from a single cataclysm but from countless petty incursions.

This narrative reveals the theory’s essence: decline stems from tolerated increments, not isolated catastrophes.

Each unrepaired defect signals eroding guardianship, emboldening opportunists. The factory’s fate mirrors countless real neighbourhoods, underscoring that human behaviour follows the environment’s lead.

1.3 The Revelation: It Wasn’t One Big Crime, It Was Hundreds of Small Ones.

When the official investigating the factory’s decline pieced together its history, he discovered something profound: the building had not been destroyed by a gang, a syndicate, or a dramatic event.

It had succumbed to:

- a thrown stone

- a scrawled tag

- a discarded bag of rubbish

- a kicked‑in door

- a smashed light

- a missing sign

Each act was insignificant alone. Together, they produced total collapse.

This is the heart of Broken Window Theory: systemic failure often masquerades as gradual entropy. Neglect begets neglect.

Each breach lowers the threshold for the next. The environment teaches people what level of care is acceptable.

1.4 The Counterfactual: What If the First Window Had Been Replaced?

This leads to the haunting counterfactual:

What if someone had replaced that first broken window?

Would graffiti have followed?

Would vandals have tested the door?

Would the building still stand today as a symbol of pride rather than decay?

Decades of research affirm the answer: yes.

Swift intervention halts the cascade.

Fixed windows signal vigilance; standards endure.

Behavioural experiments, from controlled lab studies to real‑world urban trials, confirm that early restoration elevates norms.

Tolerate the first flaw and entropy accelerates; repair it and order reinforces itself. In CMMS terms, ignoring a blank failure code or a duplicate asset record invites pervasive data sloppiness.

1.5 The New York Experiment: Fix Everything, No Exceptions.

For a decade, Broken Window Theory remained largely academic, until New York City tested it at scale in the 1990s.

The city was in crisis. Crime was high. Public spaces felt unsafe. The subway system had become a rolling canvas of vandalism.

Mayor Rudy Giuliani and Police Commissioner William Bratton implemented a radical standard: fix every visible defect immediately.

This meant:

- Slashed subway seats were reupholstered overnight.

- Graffiti‑etched train windows were replaced before commuters saw them twice.

- Spray‑painted signposts were cleaned or repainted within hours.

- Fare‑beating was enforced consistently, not selectively.

- Graffiti on subway cars was removed within 24 hours, every time.

The strategy wasn’t about aesthetics. It was about psychology.

When people saw order being restored quickly and consistently, they behaved differently. When they saw that standards mattered, they acted as though standards mattered.

Crime dropped dramatically. Public spaces became safer. And the world learned a lesson that would echo far beyond policing:

If you tolerate small defects, you invite larger ones.

If you eliminate small defects, you prevent larger ones.

1.6 The Psychology of Visible Disorder.

At its core, Broken Window Theory rests on norm signalling, the idea that environments dictate acceptable conduct.

Visible disorder, shattered glass, faded signs, accumulating trash, triggers subconscious inferences:

- “Disorder prevails here.”

- “Enforcement has lapsed.”

- “Conformity is optional.”

Cognitive psychology calls this the broken windows effect: minor cues prime antisocial escalation.

Neuroscience adds that mirror neurons and social proof heuristics cause observers to mimic perceived norms.

Clean environments foster restraint; squalor liberates impulses. This bridges seamlessly to digital realms: A CMMS riddled with inconsistencies whispers the same message, eroding user diligence and inviting shadow systems.

2.0 The Evolution: From Crime Prevention to Industrial Safety.

Broken Window Theory did not remain confined to policing.

Once Wilson and Kelling articulated the psychological mechanism, that small visible defects shape human behaviour, other industries quickly recognized the same pattern in their own environments.

Nowhere was this more evident than in industrial safety and world‑class manufacturing, where the stakes were measured not in vandalism or graffiti, but in injuries, equipment failures and operational risk.

The theory’s migration from urban streets to industrial plants was not accidental.

It happened because the underlying psychology is universal: people calibrate their behaviour based on the standards they see enforced around them.

When small hazards are tolerated, larger hazards follow. When precision is visible, precision becomes the norm.

2.1 New York City’s Broken Windows Experiment.

Before industry adopted the theory, New York City proved it at scale.

In the early 1990s, the city was struggling with high crime, deteriorating public spaces and a subway system that had become a symbol of urban decline.

Mayor Rudy Giuliani and Police Commissioner William Bratton implemented a radical strategy: fix everything, no exceptions.

This meant:

1. Slashed subway seats were reupholstered immediately.

2. Graffiti‑etched train windows were replaced overnight.

3. Spray‑painted signposts were cleaned or repainted before commuters saw them twice.

4. Fare‑beating was enforced consistently, not selectively.

5. Graffiti on subway cars was removed within 24 hours, every single time.

The goal was not cosmetic improvement. It was psychological reset.

By restoring visible order, the city restored social norms. By eliminating small signs of disorder, it prevented larger ones.

The results were historic. Crime dropped dramatically. Public confidence returned. And the world saw that small corrections, applied consistently, can reverse large‑scale decline.

This lesson resonated far beyond policing.

2.2 Slashed Seats, Graffiti‑Etched Windows and the 24‑Hour Rule.

One of the most powerful elements of the New York experiment was the 24‑hour rule: any visible defect must be corrected before it becomes a signal of neglect.

This rule was applied relentlessly:

- A slashed seat discovered at 10 p.m. was repaired before the morning commute.

- A train window etched with graffiti was replaced the same night.

- A vandalized signpost was cleaned or repainted within hours.

The city understood something profound: the speed of correction mattered more than the size of the defect.

This principle, rapid response to small problems, would soon become a cornerstone of industrial safety and operational excellence.

2.3 Behavioral‑Based Safety (BBS): Zero Tolerance for Small Hazards.

By the late 1990s, industrial safety leaders recognized the same behavioural patterns Wilson and Kelling described.

On oil rigs, in chemical plants, in mining operations and in manufacturing facilities, safety professionals observed that:

1. A small oil leak ignored today becomes a major leak tomorrow.

2. A frayed cable tolerated today becomes an electrocution hazard tomorrow.

3. A tool left on a walkway today becomes a trip injury tomorrow.

4. A missing lockout tag today becomes a fatality tomorrow.

The psychology was identical to urban decay: when workers see small hazards tolerated, they subconsciously conclude that safety standards are slipping.

This realization fuelled the rise of Behavioural‑Based Safety (BBS), a movement built on observation, feedback and reinforcement. BBS practitioners understood that culture is shaped not by policies, but by what leaders tolerate.

If a supervisor walks past a small hazard without addressing it, the entire crew learns that shortcuts are acceptable.

If a supervisor stops work to correct a minor issue, the crew learns that precision matters. The parallels to Broken Window Theory were unmistakable.

2.4 5S and the Japanese Manufacturing Interpretation.

Long before Broken Window Theory was formally articulated, Japanese manufacturing, particularly the Toyota Production System, had already operationalized its principles through 5S:

I. Sort

II. Set in Order

III. Shine

IV. Standardize

V. Sustain

The “Shine” step, which requires immediate correction of any deviation from standard, is pure Broken Window thinking.

Examples:

1. A machine leaks oil, it is cleaned immediately.

2. A tool is left out of place, it is returned to its shadow board instantly.

3. A surface becomes dusty, it is wiped before the next shift.

Toyota’s andon cord system reinforced the same principle: any worker can stop the entire production line if they spot a defect.

This empowerment sends a powerful message: small problems are never ignored. Quality is absolute.

The result is a culture where precision is normal and defects are rare.

2.5 The Universal Principle: Order Maintained = Behaviour Elevated.

Across policing, safety and manufacturing, the same universal truth emerges:

People elevate their behaviour when they see standards enforced. People lower their behaviour when they see standards ignored.

This is the psychological engine behind Broken Window Theory.

- In New York, clean trains produced safer streets.

- In industrial plants, clean work areas produced safer operations.

- In manufacturing, clean processes produced higher quality.

And now, in the digital age, the same principle governs CMMS master data.

Because a CMMS is not just a database, it is a digital environment and like any environment, it teaches people how to behave.

3.0 Buker Business Excellence.

An Operational Discipline That Aligns With Broken Window Theory.

Broken Window Theory explains the psychology of disorder, how small visible defects shape human behaviour.

Buker Business Excellence arrives at the same conclusion from a different direction: through operational discipline, binary standards and process integrity.

These two frameworks do not sit in a hierarchy.

They sit side by side, reinforcing one another.

1. Broken Windows teaches that small defects signal neglect.

2. Buker teaches that small defects are neglect.

3. TPM/5S teaches how to eliminate those defects through daily practice.

Together, they form a unified philosophy: precision is cultural and culture is built through visible standards.

Buker’s methodology gives Broken Window Theory its operational backbone, the ruler that determines whether a window is broken in the first place.

3.1 Why Psychology Needs Standards.

Broken Window Theory tells us that small defects matter because they change how people behave. However, psychology alone cannot govern a business.

Organizations need standards, clear, objective, measurable definitions of what “good” looks like.

This is where Buker Business Excellence enters the picture.

Buker eliminates ambiguity. Where most companies tolerate “close enough,” Buker insists on binary clarity:

1. A process is either followed or not.

2. A dataset is either complete or incomplete.

3. A record is either accurate or inaccurate.

This aligns perfectly with the Broken Windows principle that there is no such thing as a harmless defect.

3.2 The Binary Model: Green Ticks and Red Crosses.

Buker’s Class A Business Excellence model is built on a simple but transformative idea:

Excellence is binary.

There is no “almost.” There is no “95% correct.” There is no “we’ll fix it later.”

Every process, dataset and transaction is evaluated using a two‑symbol system:

- Green Tick (✓): The standard is met 100%.

- Red Cross (✕): Anything less than 100%.

This is the corporate equivalent of New York City’s 24‑hour rule:

- A window is either intact or broken.

- A train seat is either slashed or whole.

- A signpost is either vandalized or clean.

There is no middle category.

Buker’s philosophy aligns with Broken Window Theory because both frameworks recognize the same truth:

Small deviations are not small, they are signals.

A single Red Cross in a critical process is the organizational equivalent of a broken window on a quiet street corner.

It tells everyone:

- “Standards are optional.”

- “Precision is negotiable.”

- “Nobody is watching.”

And once that belief takes hold, decline accelerates.

3.3 How Buker Defines a “Broken Window” in Business.

In the Buker space, a broken window is any deviation from the documented standard, no matter how small.

Examples:

1. A missing field in a master data record.

2. A BOM that is 95% complete.

3. A work order closed without a failure code.

4. A spare part with inconsistent naming.

5. A PM task list missing one inspection step.

These are not clerical imperfections. They are Red Crosses, signals of disorder that propagate through the organization.

Buker’s insight is that every Red Cross has downstream consequences, even if the defect appears trivial in isolation.

This is the same logic that destroyed the abandoned factory in Section 1.

It is the same logic that transformed New York City in Section 2 and it’s the same logic that destroys CMMS trust in the following Section 4.0.

3.4 The Triple Bottom Line (TBL) Lens.

To elevate the stakes further, Buker’s framework aligns naturally with the Triple Bottom Line (TBL), a model that evaluates organizational performance across:

1. People

2. Planet

3. Profit

When viewed through this lens, each data defect becomes a TBL Red Cross with real consequences.

Below is a table that covers this.

|

TBL Pillar |

The Broken Window (Data Error) |

The Consequence (Red Cross) |

|

Profit |

Duplicate spare parts in the master data |

Excess inventory, emergency freight, inflated carrying costs |

|

People |

Outdated safety procedures attached to a Work Order |

Increased injury risk; culture of “the system is always wrong” |

|

Planet |

Incorrect calibration records for emissions sensors |

Environmental breaches, regulatory fines, unplanned downtime |

This table makes the point unmistakable: data defects are not administrative issues, they are operational, financial and environmental risks.

3.5 Why 95% Accuracy Is Still Failure.

Buker’s most important contribution to CMMS governance is this:

95% accuracy is not “good.” It is failure.

Why?

Because the remaining 5%:

1. Contains the defects that destroy trust.

2. Creates the workarounds that bypass the system.

3. Generates the errors that propagate through planning, scheduling, inventory and compliance.

4. Sends the psychological signal that “nobody is watching.”

In other words:

That 5% is where the broken windows live.

Once users see those broken windows, they behave accordingly.

3.6 The Bridge to CMMS: Red Crosses in Master Data.

This is the moment where Buker and Broken Windows converge:

“For my way of thinking, If Mayor Giuliani taught us that small crimes lead to big chaos, David Buker taught us that small data ‘Red Crosses’ lead to operational failures.”

A CMMS with:

- 95% accurate equipment lists

- 90% complete BOMs

- 85% consistent naming conventions

- 80% populated failure codes

…is not “mostly correct.”

It is a digitally vandalized neighbourhood.

A place where:

- Planners stop trusting the data

- Technicians create shadow systems

- Engineers stop bothering to analyse trends

- Supervisors bypass the CMMS entirely, they might feel it’s nothing more than a waste of time and money.

This is why Section 4.0 begins with a simple truth:

CMMS master data is the new neighbourhood and Buker gives us the standard that tells us whether that neighbourhood is clean or collapsing.

4.0 The Bridge: Why CMMS Master Data Is the New “Neighbourhood.”

By this point in the article, you’ve seen Broken Window Theory proven in criminology, validated in industrial safety and reinforced through Buker’s operational discipline.

Now we cross the bridge into the digital world, where the same psychology, the same standards and the same consequences apply with equal force.

A CMMS is not just a database, it’s a digital environment, a living neighbourhood.

A place where people work, make decisions and interpret signals every day.

Just like any physical neighbourhood, a CMMS can develop its own ‘broken windows’, if we let it.

4.1 Data as Digital Infrastructure.

In a modern maintenance organisation, the CMMS is the operational nervous system, it governs:

1. Asset hierarchies.

2. Equipment specifications.

3. Preventive maintenance strategies.

4. Spare parts catalogues/bills of materials/application parts lists.

5. Work order history

6. Failure analysis.

7. Compliance details.

This data is not administrative, it’s the infrastructure, the digital equivalent of roads, street signs and buildings.

When that infrastructure is clean, consistent and complete, people navigate confidently. When it is broken, inconsistent, or incomplete, people will avoid it.

This is the first psychological bridge: users respond to digital disorder the same way they respond to physical disorder.

4.2 What a “Broken Window” Looks Like in a CMMS.

Unlike physical broken windows, CMMS defects are not always visible to everyone. However, they are immediately visible to the people who rely on the system every day.

These defects share the same characteristics as physical broken windows:

1. They are clearly wrong.

2. They violate reasonable expectations.

3. They signal that nobody is maintaining order.

Examples include:

Asset Master Data Defects.

1. Equipment records missing critical fields (“TBD”, “Unknown”, “N/A”)

2. Placeholder installation dates (“01/01/1900”)

3. Duplicate equipment entries with slight naming variations.

4. Equipment upgrades have happened but the Master Data not updated, a sizeable portion of the master data is now invalid.

5. Asset descriptions that say “See manual” instead of actual specifications

6. It’s obvious that to create an equipment number/function location, that only the bare information was entered to enable creation, apart from the fact it exists as a tag, it’s basically useless.

Naming and Consistency Defects.

1. Inconsistent naming conventions across plants or departments.

2. Spare parts with wildly different descriptions for identical items.

3. Location codes that don’t follow documented standards.

Work Order Defects.

1. Closed work orders with no failure code.

2. Work descriptions that say only “Fixed” or “Replaced part.”

3. Blank fields for labour hours, parts used, or actual duration.

4. Priority codes used inconsistently (“everything is urgent”).

Spare Parts/Materials Inventory Defects.

1. Parts with no equipment linkage, people with local knowledge will know what they are for, people their own personal ‘cheat sheets’ (spreadsheets or notepads with the necessary information) will know what they are for, to anyone new or without that local knowledge, those parts are just sitting in a warehouse collecting dust

2. Inventory quantities that don’t match reality, often happens when the full spectrum of Master Data work hasn’t happened after engineering projects have introduced new equipment and decommission others etc.

3. Duplicate inventory identification for the same OEM part number item.

4. Missing or incorrect units of measure (this can create wasteful overhead costs), a UI of EA for a 50m roll of rubber, so instead of 1 x ROLL of Rubber, you end up with 50 x 50m rolls of rubber.

PM Program Defects.

- Vague task list header description (“13w Check pump”)

- PM Intervals that don’t match OEM recommendations, you’ve decided you know better than the people that made the equipment, came to site, evaluated where and how it would be used and via their substantial intelligence in this specialized, gave you the best possible maintenance strategy for that equipment.

- PMs with automated parts lists and/or service orders for vendors generating purchase orders or picking slips for equipment that was removed from site 3 years ago.

- Resources listed as “TBD”

Hierarchy and Relationship Defects.

- Orphaned child assets (Parent/Child relationships not completed)

- Cost centers that no longer exist or that have been changed and constantly generate error reports and are causing primary node budget information to be constantly wrong.

- Equipment marked “Active” that is now mothballed for 8 months due to operational circumstances.

These are the digital equivalents of:

- A slashed subway seat.

- A graffiti‑etched train window.

- A vandalized signpost.

- A smashed light.

- A broken factory window.

They are small, but they are signals.

4.3 How Users Interpret Data Defects.

This is where the psychology becomes unavoidable.

When users encounter data defects, they make immediate, often subconscious, judgments about whether precision matters in this environment.

The Planner

Opens an asset record and sees missing specifications. Internal response:

“If nobody bothered to provide me with accurate or worthwhile information, why should I spend extra time being detailed with the work scope?”

The Technician

Searches for a part and finds duplicates or spends longer searching for parts than it took to do the actual job, their response, “Given that the inventory is useless, I’ll just keep my own notes.”

The Reliability Engineer.

Reviews work orders with no failure codes. Internal response:

“I’ve been asking for discipline when it comes to filling out the failure information when completing a work order since I first started working here, given nobody seems to care about doing it, maybe I just stop analysing it.”

The Supervisor.

Sees PMs generating for decommissioned equipment. Internal response:

“Nobody’s bothered to turn this PM off. I’ll just mark them complete and get the parts returned back to the store.” Sometimes they just decide to stash them inside a 40ft sea container too, when people give up on system integrity, the easiest way of dealing with problems is the path of least resistance and the least amount of stress, so that’s the path you’ll find a lot of people on.

What Does It All Mean?

These reactions are not laziness. They are environmental responses, the same responses New Yorkers had when they saw vandalized trains and broken windows. The problem is, without the right type of intervention, it only gets worse. The CMMS is teaching them how to behave.

4.4 The Cascade: From First Defect to System Abandonment.

Just like physical neighbourhoods, CMMS environments do not collapse all at once. They deteriorate through a predictable cascade (below are my best guesses on the timeline):

Month 0–6: The First Broken Windows.

- A project closes without full data integration.

- Some equipment records are incomplete.

- Users notice, but work around the gaps.

- Trust is dented, but not broken.

Month 6–18: Multiplication.

- More projects skip proper integration.

- Duplicate entries appear.

- Naming conventions drift.

- New staff learn workarounds from existing staff.

- Data entry becomes careless (“the system’s half wrong anyway”).

Month 18–36: Avoidance

- Users actively avoid the CMMS.

- Shadow spreadsheets proliferate.

- Work orders are entered minimally for compliance.

- Real coordination happens through phone calls and memory.

Month 36+: Abandonment.

- PM programs fail.

- Spare parts shortages become chronic.

- Costs spike due to reactive maintenance.

- Leadership commissions an expensive “data clean-up project”.

- The CMMS is now a system people comply with, not rely on.

This is the digital equivalent of the abandoned factory.

Not one big failure, but hundreds of small ones, tolerated over time.

5.0 Why Data Decay Is Dangerous.

By now, you understand that a CMMS is a digital neighbourhood, that data defects are broken windows and that users respond to those defects in predictable psychological ways.

This section now sets about answering the next critical question:

“What actually happens when data decay is allowed to spread?”

The consequences are not abstract, they are operational, financial, cultural and regulatory. They affect people, equipment, safety, inventory and decision‑making.

Data decay is not a nuisance. It is a systemic risk, one that compounds silently until the organization is forced into crisis mode.

5.1 The Trust Erosion Cycle.

Data decay begins with a single defect, but its most dangerous effect is the erosion of trust.

Once trust is damaged, the CMMS stops being a system of record and becomes a system of compliance theatre, something people use only because they must, not because they rely on it.

The erosion follows a predictable four‑stage cycle:

Stage 1: Doubt.

Users encounter their first significant data errors:

- An asset location is wrong, now located at the other end of site lease, a 20 minute drive from the location identified on the work order and a lot of time is wasted finding that out.

- A material number for a particular part doesn’t seem to exist in the catalogue, bill of materials etc.

- A PM task list is outdated or hardly worth the paper it’s printed on.

- A work order completion history is either incomplete or just not there for a 3 million dollar breakdown repair that took 4 weeks.

They begin double‑checking information before relying on it.

Trust is dented, but not broken.

Stage 2: Workarounds.

After repeated errors, users stop trusting the CMMS as the single source of truth.

They create and tend to prefer:

- Personal spreadsheets in their “My Documents”.

- Handwritten notebooks in their shirt pockets.

- Shared network drive folders have more useful information than the CMMS.

- Those people with ‘Local knowledge’ are keeping the place running on a weekly basis, they know better than what’s contained within the CMMS.

The CMMS becomes a secondary reference.

The real system becomes whatever the users build for themselves.

Stage 3: Avoidance.

Users actively circumvent the CMMS:

- Parts ordering happens through phone calls.

- Parts are delivered as part of a service order, there’s no evidence that they were received, no history of the parts being replaced, no parts receival quality checks etc.

- Equipment history is learnt by asking technicians.

- PMs are marked complete without even bothering to check if the task lists are accurate or worthwhile (no red pen markups).

- Planners rely on memory instead of data and an array of spreadsheets and word documents possess the information that should be in the CMMS.

The CMMS becomes an expensive to maintain bureaucratic burden, something to ‘get through’, that people are forced to use, regardless of its quality rather than something that adds value and is essential to the operational success.

Stage 4: Abandonment.

The organization effectively has no functional maintenance management system.

- New staff cannot be trained properly.

- Institutional knowledge lives in people’s heads.

- Spare parts management stories become the source of jokes.

- PM programs lose credibility.

- Reliability engineering becomes practically impossible to do properly.

This is the digital equivalent of the abandoned factory in section 1.0, not one big failure, but hundreds of small ones, tolerated over time.

5.2 The Operational Consequences.

Data decay does not stay contained in the CMMS. It manifests as tangible operational failures.

Planning and Scheduling Collapse

When asset data, BOMs and task lists are unreliable:

- Planners cannot prepare accurate scopes of work, work packs etc.

- Technicians arrive at jobs after a 15 minute drive, missing parts or tools that the work order should have instructed them to pick up prior to leaving the workshop.

- Actual job durations, the number of people required to do the work, the types of trades required to do the work, the parts required, the standard and/or special tools lists etc are nothing like the planned requirements.

- Rework becomes quite normal.

- The backlog grows weekly.

The organization slides towards a state of reactive maintenance only.

Inventory Management Fails.

Without accurate parts‑to‑equipment linkages and consumption history:

- critical parts stock out unexpectedly

- emergency purchases skyrocket

- obsolete inventory accumulates

- reorder points become guesswork

- storerooms lose credibility

Inventory becomes a cost centre instead of a reliability enabler.

PM Programs Lose Effectiveness

When PM task lists are vague, outdated, or misaligned:

- non‑critical assets are over‑maintained

- critical assets are under‑maintained

- technicians stop trusting PMs

- PM compliance becomes a checkbox exercise

- failures increase despite “high compliance”

This is one of the most dangerous forms of data decay, the illusion of control.

Analysis Becomes Impossible

Reliability engineering depends on:

- accurate failure codes

- complete work order history

- consistent naming

- structured data

When these are missing:

- RCA becomes guesswork

- bad actors cannot be identified

- improvement initiatives stall

- leadership loses visibility

The organization becomes blind.

Compliance Risk Escalates

Regulators increasingly expect:

- documented maintenance

- calibration records

- traceable work history

- evidence of systematic PM execution

Data decay creates:

- audit findings

- fines

- forced shutdowns

- reputational damage

This is where broken windows become broken businesses.

The Circle of Despair: When Data Defects Trap Technicians in Reactive Hell.

No CMMS failure manifests the Broken Window effect more destructively than the Circle of Despair, a vicious loop where data neglect turns maintenance into Sisyphean drudgery.

Here’s how it unfolds when technicians encounter inconsistent asset specs, blank failure codes and incomplete histories:

1. Six-Month Service, No Clarity, Insufficient Details.

A technician services equipment using vague work order information. They rely on memory and prior experience.

During the job, they notice what seem to be incorrect parts and replace them with what they believe is right. Unbeknownst to them:

- The original parts were upgraded to exotic materials.

- The removed parts cost 4x more than the incorrect replacements they’ve just installed.

- The upgrade material specifications were never documented in the CMMS and added to the bill of materials etc.

2. Rapid Re-Failure

The equipment fails again within days. Root cause: premature wear.

However, the failure isn’t traced correctly because:

- Specs were missing, people don’t know what they don’t know, the technician was unaware he was putting installing the wrong replacement parts.

- Upgrade notes were never captured and implemented within the CMMS.

- Failure codes are useless, people already know that that equipment was and now still is failing from.

- History is incomplete and/or of zero worth.

No one realizes this is the same issue that caused previous losses and the solution (the new upper spec materials are sitting on a shelf in the warehouse).

3. Rushed Rework.

An emergency callout at 2:00 AM. The technician, exhausted and under pressure, repeats the ineffective fix. They skip diagnostics, can’t reach anyone for context, and close the work order with “Fixed.” No failure code. No useful notes. No learning captured.

4. No Learning, No Update.

The CMMS remains unchanged. No prompt to update the Task List. No trigger to revise the Standard Job and/or Bill Of Materials. The reliability engineer sees “Pump fixed” but doesn’t know the wrong parts are still being used.

5. The Cycle Repeats.

The same flawed master data continues to generate PMs and work orders. Nothing improves. Money is wasted. Production is lost. Trust evaporates. The system is letting everyone down.

Each Loop Compounds the Damage

1. Time Waste: 60–80% of effort spent on repeat visits instead of prevention.

2. Cost Explosion: Emergency rework costs 3–5x more than planned service.

3. Material Waste: Upgraded parts sit unused in the warehouse.

4. Production Losses: Reliability drops, uptime suffers, targets are missed.

5. Morale Collapse: Technicians feel like “glorified janitors” and build shadow systems.

6. Reliability Stagnation: Fast-wearing components persist indefinitely due to bad data.

Broken Window Link.

Each defect triggers another. Each failure reinforces the next.

The Circle of Despair spins faster, until the system collapses under the weight of its own neglect.

Real-World Escape.

Organizations that enforce zero-tolerance master data stewardship break the cycle. They fix the first broken window.

They prevent the second. They restore trust, reliability and control.

That’s the plain truth and it’s the only way out of the circle of despair.

5.3 The Compounding Effect of Data Defects.

Physical broken windows spread linearly. Digital broken windows spread exponentially.

One bad asset record creates:

- Bad work orders.

- Bad parts transactions.

- Bad inventory reports.

- Bad purchasing decisions.

- Bad PM strategies.

- Bad cost centre allocations.

Each defect multiplies downstream. Each downstream defect multiplies again.

This is why data decay accelerates over time:

- Year 1: 5–10% efficiency loss

- Year 2: 20–30% efficiency loss

- Year 3: crisis

The CMMS becomes a liability instead of an asset.

5.4 The 10x–25x Cost Multiplier of Delayed Correction.

Fixing a data defect immediately is cheap. Fixing it years later is expensive.

Prevention (fixing immediately):

- Scope: one project’s incomplete integration.

- Documentation: readily available.

- Effort: 40–80 hours.

- Cost: $2,000–$5,000.

Recovery (after years of decay):

- Scope: multiple projects’ accumulated backlog.

- Documentation: scattered or lost.

- Effort: 500–1,000+ hours.

- Cost: $50,000–$150,000.

This is the 10x–25x multiplier, the financial equivalent of ignoring the first broken window.

And this does not include:

1. Lost production.

2. Emergency purchases.

3. Increased downtime.

4. Inflated inventory.

5. Regulatory penalties.

6. Cultural damage.

The true cost of data decay is far greater than the clean-up project.

6.0 The Solution: Zero Tolerance for Data Disorder.

If Broken Window Theory teaches us that small defects shape behaviour and Buker Business Excellence teaches us that excellence is binary, then the solution becomes unavoidable:

Zero tolerance for data disorder.

Not perfectionism. Not bureaucracy. Not endless clean-up projects.

Zero tolerance means:

- Visible defects are corrected immediately.

- Standards are enforced consistently.

- Users see that someone is watching.

- Data quality becomes cultural, not clerical.

This is the digital equivalent of New York City’s 24‑hour rule: fix the small things fast and the big things rarely emerge.

Zero tolerance is not a slogan. It is a system, a philosophy supported by roles, routines and rapid response.

6.1 The Core Philosophy.

Zero tolerance for data disorder is built on three principles:

1. Small defects matter more than big ones.

Big failures are usually the result of dozens of small ones. Fixing the small ones prevents the big ones.

2. Speed of correction matters more than size of correction.

A defect fixed in 24 hours sends a message of vigilance. A defect left for weeks sends a message of neglect.

3. Standards must be visible, enforced and non‑negotiable.

If a standard is not enforced, it is not a standard, it is a suggestion.

This philosophy transforms the CMMS from a passive database into a living environment where precision is normal and disorder is unacceptable.

6.2 The 24‑Hour Rule for Data Defect Correction.

Inspired by New York’s graffiti‑removal strategy, the 24‑hour rule is the single most powerful tool for preventing CMMS decay.

The Rule:

Any data defect visible to users must be corrected within one business day.

This includes:

- Missing fields.

- Incorrect locations.

- Duplicate assets.

- Inconsistent naming.

- Blank failure codes.

- Inaccurate PM intervals.

- Orphaned child assets.

- Incorrect part linkages.

Why 24 hours?

Because the psychology of Broken Windows is about signals, not severity.

A defect corrected quickly tells users:

- “Standards matter here.”

- “Someone is maintaining order.”

- “You can trust this system.”

A defect left uncorrected tells them the opposite.

Implementation

- User‑reported defects → fixed same day or next morning

- Audit‑discovered defects → prioritized and communicated immediately

- Project integration gaps → never allowed to go live

The 24‑hour rule is not about technical difficulty. It is about psychological impact.

6.3 Data Stewards: The Digital Neighbourhood Watch.

Zero tolerance requires visible guardians, people responsible for maintaining order in the digital environment.

These are Data Stewards.

Their role is simple but powerful:

- enforce standards

- correct defects

- validate new data

- educate users

- escalate systemic issues

- maintain the integrity of their domain

Time commitment

- Small operations: 4–8 hours/week

- Medium operations: 40–60% of a role

- Large operations: full‑time

Distributed ownership model

Assign stewards by asset class:

- rotating equipment

- electrical equipment

- static equipment

- instrumentation

- facilities

- spare parts

This mirrors the “neighbourhood watch” concept, each steward owns a block of the digital city.

Visibility matters

Everyone should know:

- who the stewards are

- what they own

- how to report defects

- how quickly defects are fixed

Stewards are the human embodiment of the 24‑hour rule.

6.4 Micro‑Audits and Daily/Weekly/Monthly Quality Routines.

Traditional CMMS audits are too slow and too broad. Zero tolerance requires micro‑audits, small, frequent, targeted checks that catch broken windows before they spread.

Weekly Spot‑Checks (15 minutes)

- Randomly select 5 assets

- Verify naming conventions

- Check mandatory fields

- Confirm specifications

- Perform a “professionalism smell test”

Monthly Micro‑Audits (45 minutes)

- Review 10 recently closed work orders

- Check 15 new spare parts for proper linkages

- Validate 5 modified PM strategies

- Spot‑check 10 assets for location accuracy

Quarterly Consistency Audits (2 hours)

- Run reports for duplicates

- Check naming convention compliance

- Validate project integration

- Review data quality metrics

Why micro‑audits work

- they are fast

- they are visible

- they reinforce standards

- they prevent cascades

- they build culture

Micro‑audits are the digital equivalent of walking the neighbourhood every day.

6.5 Eliminating Duplicate Work Requests and Backlog Inflation.

One of the most pervasive forms of digital disorder in a CMMS is the silent accumulation of duplicate notifications and duplicate work orders. These duplicates often arise because:

- different people describe the same problem in different words

- the original work order is hard to find

- the asset hierarchy is unclear

- the requester does not trust that the issue is being addressed

- the system does not enforce pre‑submission checks

The result is a backlog that grows artificially, not because the plant is failing, but because the CMMS is.

Why duplicates are dangerous

Duplicate work orders:

- inflate backlog size

- distort planning and scheduling priorities

- create false indicators of asset unreliability

- waste labour on triage and investigation

- cause planners to prepare multiple jobs for the same issue

- confuse technicians in the field

- undermine confidence in the system

This is a classic Broken Window effect: when users see duplicates, they assume the system is unmanaged, so they stop checking before raising new requests.

Zero‑tolerance solution

A zero‑tolerance CMMS requires:

- automated duplicate detection

- mandatory asset selection

- mandatory search before submission

- planner review before work order creation

- clear asset naming and hierarchy

- visible status updates so users know the issue is already being addressed

This is the digital equivalent of removing graffiti before commuters see it twice.

6.6 Engineering Projects Must Not Close Until CMMS Integration/Updates Is/Are 100% Complete.

One of the most damaging sources of CMMS decay is incomplete integration of new equipment from engineering projects.

This is where many organizations unintentionally create entire clusters of broken windows. The rule is simple:

No engineering project should ever be signed off as complete until the CMMS master data is 100% correct, complete and active and the maintenance strategy is fully approved and switched on.

This includes:

- complete asset records

- correct functional locations

- accurate naming conventions

- full equipment specifications

- approved preventive maintenance tasks

- approved predictive maintenance tasks

- BOMs and spare parts linkages

- criticality assessment

- failure modes and effects

- warranty information

- commissioning documentation

- calibration requirements

- safety procedures

And just as importantly:

Old assets must be physically removed and digitally deactivated.

This means:

- decommissioning the old equipment

- turning off PMs for assets that no longer exist

- deactivating functional locations

- removing obsolete parts from active inventory

- ensuring no work orders can be raised against retired assets

Why this matters

If new assets go live without complete data:

- planners cannot plan

- technicians cannot execute

- reliability engineers cannot analyse

- storerooms cannot stock correctly

- PMs cannot run

- compliance cannot be demonstrated

And if old assets remain active:

- PMs generate for equipment that no longer exists

- costs are charged to the wrong assets

- backlog grows artificially

- failure history becomes polluted

- reliability metrics become meaningless

This is the digital equivalent of leaving the old, abandoned factory standing next to the new one, broken windows and all.

Zero‑tolerance project integration

A world‑class CMMS requires:

- a formal CMMS integration checklist

- a mandatory data quality gate before project closeout

- sign‑off by the Data Steward, not just Engineering

- a rule that “temporary placeholders” are never allowed

- a requirement that PMs must be active before handover

- a requirement that old assets must be deactivated before handover

This is how you prevent entire neighbourhoods of digital disorder from being created in a single day.

6.7 Building a Culture of Precision.

Culture is not created by policies. Culture is created by what leaders tolerate and what they correct.

To build a culture of precision:

Leaders must reference CMMS data in decisions.

This signals that data matters.

People must be held accountable for data quality.

This includes recognition for excellence and coaching for poor habits.

Broken windows must never be ignored.

Temporary workarounds must have expiration dates.

Training must explain why data matters, not just how to enter it.

People protect what they understand.

Mistakes must be treated as learning opportunities.

Blame creates hiding. Coaching creates improvement.

Wins must be celebrated.

When accurate data prevents a failure, tell the story.

Culture is built through repetition, visibility and reinforcement.

6.8 The First 90 Days: How to Turn the Tide.

A zero‑tolerance program does not take years to implement. It takes 90 days to change perception and behaviour.

Week 1: Establish the Standard

- appoint data stewards

- identify 10–15 visible broken windows

- fix them immediately

- communicate the new standard

Weeks 2–4: Demonstrate Consistency

- run weekly spot‑checks

- correct every defect within 24 hours

- acknowledge fixes publicly

Month 2: Build the Process

- implement micro‑audit schedule

- create defect reporting channels

- track metrics

- hold first governance meeting

Month 3: Expand Ownership

- assign domain‑specific stewards

- integrate data quality into performance conversations

- enforce project integration standards

- document lessons learned

By Day 90, users should be saying:

“They’re actually fixing things now.” “The data is getting better.” “The system is becoming reliable again.”

This is the turning point.

6.9 Technology Enablers and Automated Prevention.

Technology cannot replace culture, but it can reinforce it.

Automated Validation Rules

- mandatory fields

- format checks

- parent‑child verification

- naming convention enforcement

These are the digital equivalent of building codes.

Data Quality Dashboards

- completeness

- consistency

- duplicates

- orphaned records

- failure code usage

Dashboards make broken windows visible.

Workflow Controls

- prevent incomplete records from going live

- enforce approvals

- require documentation for changes

Integration Standards

- ensure new projects deliver complete data

- prevent “temporary” placeholders

- eliminate post‑project cleanup

Technology is not the solution, but it is a powerful ally.

6.10 Decommissioning, Replacement & Asset Status Changes: Eliminating Digital Ghosts

One of the most overlooked sources of CMMS decay is the mishandling of asset lifecycle transitions. When assets are:

- removed

- replaced

- mothballed

- capped

- parked up

- temporarily inactive

- permanently decommissioned

…the CMMS must be updated immediately and comprehensively.

If not, the system becomes polluted with digital ghosts, assets that no longer exist physically but remain active digitally.

These ghosts generate:

- PMs for equipment that is gone

- work requests for assets that no longer exist

- backlog entries that inflate KPIs

- confusion for planners and technicians

- incorrect cost allocations

- false reliability signals

- wasted time and wasted effort

This is pure Broken Window Theory: a single ghost asset is a broken window that signals “nobody is maintaining order.”

The Zero‑Tolerance Rule.

Whenever an asset is removed, replaced, or mothballed:

1. All open work requests must be cancelled

o with a standard comment such as: “Asset decommissioned, work no longer required.”

2. All open corrective work orders must be closed

o with a standard comment such as: “Asset decommissioned, closing work order.”

3. All PMs must be turned off or reassigned

o no PM should ever generate for a non‑existent asset.

4. The asset status must be updated immediately

o Active → Inactive

o Active → Mothballed

o Active → Decommissioned

o Active → Parked Up

5. Functional locations must be updated

o no active location should contain a decommissioned asset.

6. Old assets must be physically removed from the plant

o and digitally removed from the CMMS.

7. New assets must not go live until their data is 100% complete

o no placeholders

o no TBD fields

o no missing PMs

o no missing BOMs

This is the digital equivalent of demolishing the abandoned factory before it becomes a magnet for vandalism.

6.11 Asset Status Changes and the 8 Wastes: How Disorder Creates Waste.

When the CMMS does not reflect physical reality, it creates waste in every sense of the Lean framework.

Below is how each of the 8 Wastes aligns with Broken Window Theory and CMMS disorder:

|

Lean Waste |

Broken Window Equivalent |

CMMS Example |

Impact |

|

Defects |

Broken windows |

Incorrect asset status, wrong PMs, duplicate work orders |

Rework, confusion, lost time |

|

Overproduction |

Excess signals |

PMs generating for decommissioned assets |

Unnecessary work, inflated backlog |

|

Waiting |

Delayed repairs |

Technicians searching for correct asset or part |

Idle time, frustration |

|

Non‑Utilized Talent |

People stop caring |

Skilled staff doing clerical cleanup |

Loss of value, disengagement |

|

Transportation |

Extra movement |

Walking to verify asset identity because CMMS is wrong |

Wasted motion, wasted time |

|

Inventory |

Hoarded clutter |

Stocking parts for assets that no longer exist |

Excess inventory, tied‑up capital |

|

Motion |

Searching behaviour |

Clicking through multiple screens to find correct data |

Cognitive fatigue, inefficiency |

|

Over‑Processing |

Workarounds |

Double‑entry, spreadsheets, manual checks |

Wasteful effort, inconsistent data |

This table makes the point unmistakable:

Every broken window in the CMMS creates one or more of the 8 Wastes.

Every waste reinforces the broken windows.

Disorder and waste feed each other.

This is why zero tolerance is not optional, it is the only way to break the cycle.

7.0 Conclusion: A Thousand Broken Windows.

Broken Window Theory teaches us that environments shape behavior. Buker teaches us that excellence is binary. TPM teaches us that discipline must be daily. AI teaches us that governance can be automated. Together, they reveal a simple truth:

Your CMMS becomes what you tolerate (you get what you accept).

If you tolerate duplicates, ghost assets, incomplete PMs, vague work orders and inconsistent naming, the system will decay, not because people are careless, but because the environment teaches them that precision is optional.

If you enforce standards, correct defects quickly, deactivate old assets properly, prevent duplicate work orders and maintain alignment between physical and digital reality, the system becomes a place where people take pride in their work.

A CMMS is not a database. It is a living environment. A digital neighbourhood. A reflection of your culture.

Zero tolerance is not about perfection. It is about protecting the environment that protects your business.

AI will soon make this easier than ever. It will detect broken windows instantly, propose fixes, automate corrections and eliminate digital waste before humans even notice it. But AI cannot create standards. AI cannot create culture. AI cannot create care.

Only people can do that.

The abandoned factory in Section 1 did not collapse because of one big crime. It collapsed because nobody fixed the first broken window.

Your CMMS will follow the same path, unless you choose differently.

The future of your digital neighbourhood begins with a single decision:

Fix the first window. Fix it fast.

Fix every window after that and never let disorder take root again.

8.0 Appendices.

The following appendices provide practical tools, templates and reference materials to support the implementation of a zero‑tolerance CMMS data governance program. +These resources translate the principles of Broken Window Theory, Buker Business Excellence and TPM discipline into actionable steps that organizations can deploy immediately.

8.1 CMMS Broken Window Checklist.

This checklist helps identify the most common “broken windows” in a CMMS, the small defects that signal disorder and erode trust.

Asset Master Data

- [ ] Missing equipment specifications

- [ ] Placeholder dates (e.g., 01/01/1900)

- [ ] Duplicate asset records

- [ ] Incorrect or inconsistent naming conventions

- [ ] Orphaned child assets

- [ ] Incorrect functional location assignments

- [ ] Assets marked “Active” that no longer exist physically

Work Orders & Notifications

- [ ] Duplicate notifications for the same issue

- [ ] Duplicate work orders for the same asset/problem

- [ ] Work orders closed without failure codes

- [ ] Vague descriptions (“Fixed”, “Checked”, “Replaced part”)

- [ ] Incorrect priority codes

- [ ] Work orders still open for decommissioned assets

Preventive & Predictive Maintenance

- [ ] PMs generating for removed or inactive assets

- [ ] PM task lists missing steps or detail

- [ ] PM intervals not aligned with OEM recommendations

- [ ] PMs with “TBD” resources or materials

- [ ] PMs not linked to correct asset hierarchy

Spare Parts & Inventory

- [ ] Duplicate part numbers

- [ ] Inconsistent part descriptions

- [ ] Missing equipment linkages

- [ ] Incorrect units of measure

- [ ] Obsolete parts still marked as active

Project Integration

- [ ] New assets added without complete data

- [ ] Old assets not deactivated

- [ ] PMs not activated for new equipment

- [ ] BOMs incomplete or missing

- [ ] No commissioning documentation attached

This checklist should be used weekly by Data Stewards and monthly by CMMS governance teams.

8.2 Sample Data Steward Role Description.

Role Purpose

To maintain the integrity, accuracy and completeness of CMMS master data within their assigned domain, ensuring the system remains a trusted and reliable operational environment.

Key Responsibilities

- Enforce data standards and naming conventions

- Correct defects within 24 hours

- Validate new asset records, PMs and BOMs

- Review and approve changes to master data

- Conduct weekly spot‑checks and monthly micro‑audits

- Support planners, technicians and engineers with data quality issues

- Ensure project handovers meet CMMS integration requirements

- Maintain documentation and data dictionaries

- Report systemic issues to the CMMS Governance Committee

Required Skills

- Strong understanding of maintenance processes

- Familiarity with asset hierarchies and equipment types

- High attention to detail

- Ability to interpret engineering documentation

- Strong communication and coaching skills

Time Commitment

- Small sites: 4–8 hours/week

- Medium sites: 40–60% of a role

- Large sites: full‑time

8.3 A 30‑Day, 60‑Day, 90‑Day Implementation Plan.

This plan provides a structured roadmap for implementing a zero‑tolerance CMMS data governance program.

First 30 Days, Establish Control

Objectives

- Create visibility

- Fix the most obvious defects

- Demonstrate immediate improvement

Actions

- Appoint Data Stewards

- Publish data standards and naming conventions

- Identify 10–15 high‑visibility broken windows

- Fix them immediately

- Launch the 24‑hour rule

- Begin weekly spot‑checks

- Communicate early wins

Days 31–60, Build Structure

Objectives

- Create repeatable processes

- Expand ownership

- Strengthen governance

Actions

- Implement monthly micro‑audits

- Create defect reporting channels

- Establish a CMMS Governance Committee

- Begin project integration enforcement

- Train planners and supervisors on zero‑tolerance principles

- Build dashboards for data quality metrics

Days 61–90, Embed Culture

Objectives

- Make precision normal

- Make disorder unacceptable

- Build long‑term sustainability

Actions

- Assign domain‑specific Data Stewards

- Integrate data quality into performance conversations

- Enforce project closeout standards

- Deactivate ghost assets

- Clean up duplicate notifications and work orders

- Celebrate improvements and publish success stories

By Day 90, users should visibly trust the CMMS more and the system should feel cleaner, faster and more reliable.

8.4 Micro‑Audit Templates.

These templates support consistent, repeatable micro‑audits that prevent data decay.

Weekly Spot‑Check Template (15 minutes)

Asset ID: Functional Location: Inspector: Date:

Checks

- [ ] Naming convention correct

- [ ] Mandatory fields complete

- [ ] Specifications accurate

- [ ] Status correct

- [ ] PMs linked and active

- [ ] No duplicates

- [ ] No ghost records

Notes: Actions Required: Completed By:

Monthly Micro‑Audit Template (45 minutes)

Work Orders

- [ ] Failure codes present

- [ ] Descriptions meaningful

- [ ] Actuals recorded

- [ ] No duplicates

Spare Parts

- [ ] Descriptions consistent

- [ ] Units of measure correct

- [ ] Equipment linkages present

- [ ] No obsolete parts marked active

PMs

- [ ] Task lists complete

- [ ] Intervals correct

- [ ] Resources defined

- [ ] No PMs for inactive assets

Summary of Findings: Corrective Actions: Owner: Due Date:

Quarterly Consistency Audit Template (2 hours)

System‑Wide Checks

- [ ] Duplicate assets

- [ ] Duplicate parts

- [ ] Orphaned assets

- [ ] Inactive assets with active PMs

- [ ] Incorrect functional locations

- [ ] Naming convention compliance

- [ ] Project integration completeness

Overall Score: Key Risks Identified: Recommendations:

8.5 AI‑Enabled CMMS Governance and Automated Data Stewardship.

As CMMS environments grow in scale and complexity, the traditional approach to data governance, manual audits, periodic reports and human‑driven corrections, becomes increasingly difficult to sustain. Modern maintenance systems generate thousands of transactions per day and even the most disciplined teams struggle to keep pace.

This is where AI integration becomes transformative.

AI does not replace Data Stewards. It augments them, acting as a tireless, real‑time assistant that monitors the digital environment, detects broken windows instantly and proposes corrective actions before disorder spreads.

8.5.1 AI as a Real‑Time Broken Window Detector.

Instead of relying on:

- monthly reports

- manual queries

- CorVu dashboards

- Business Objects extracts

- Crystal Reports audits

AI can continuously scan the CMMS for:

- duplicate notifications

- duplicate work orders

- inconsistent naming

- missing fields

- incorrect statuses

- ghost assets

- PMs generating for inactive equipment

- mismatched parent‑child relationships

- incorrect units of measure

- orphaned spare parts

- incomplete BOMs

- invalid functional locations

This is the digital equivalent of having a patrol officer walking the neighbourhood 24/7.

8.5.2 AI‑Driven Recommendations and Automated Fixes.

When AI detects a defect, it can:

1. Notify the Data Steward immediately

o “A duplicate work order has been detected for Pump 4B.”

o “Asset 102‑PX‑003 has an invalid installation date.”

o “PM 450123 is generating for a decommissioned asset.”

2. Explain the issue clearly

o What it found

o Why it matters

o What the downstream impact could be

3. Propose a recommended fix

o “Merge these two work orders.”

o “Deactivate this PM.”

o “Correct the naming convention to match standard.”

o “Link this part to the correct equipment.”

4. Offer alternative options

o “Would you prefer to archive instead of delete?”

o “Would you like to apply this fix to all similar records?”

o “Should this rule be added to the automated validation engine?”

5. Execute the fix in seconds

o with Data Steward approval

o with full audit trail

o with rollback capability

This is the future of CMMS governance: AI as the first responder, humans as the decision‑makers.

8.5.3 Snapshot and Rollback: Safety for Automated Corrections.

One of the most powerful capabilities of AI‑assisted CMMS governance is the ability to:

- take a snapshot of the system state before applying a fix

- apply the correction

- validate the outcome

- revert instantly if something goes wrong

This eliminates the fear of making changes, one of the biggest barriers to data quality improvement.

It also enables rapid experimentation:

- “Fix one record.”

- “Fix 100 similar records.”

- “Fix the entire dataset.”

All with the safety net of instant rollback.

8.5.4 AI as a Force Multiplier for Data Stewards.

AI does not replace Data Stewards. It amplifies them.

A single steward, supported by AI, can:

- monitor thousands of assets

- validate millions of data points

- detect issues instantly

- correct defects in seconds

- enforce standards automatically

- maintain a clean digital environment at scale

This turns the Data Steward role from a reactive, clerical burden into a strategic, high‑impact governance function.

8.5.5 AI and the 8 Wastes: Eliminating Digital Waste at the Source.

AI directly reduces all eight forms of Lean waste:

|

Waste |

AI Benefit |

|

Defects |

Detects and corrects data errors instantly |

|

Overproduction |

Stops PMs for inactive assets |

|

Waiting |

Eliminates delays caused by searching for correct data |

|

Non‑Utilized Talent |

Frees humans from clerical cleanup |

|

Transportation |

Reduces physical verification trips |

|

Inventory |

Prevents stocking parts for decommissioned assets |

|

Motion |

Reduces unnecessary clicks and searches |

|

Over‑Processing |

Eliminates duplicate entry and manual audits |

AI is not just a convenience, it is a waste‑elimination engine.

8.5.6 The Future: Self‑Healing CMMS Environments.

The long‑term vision is clear:

- A CMMS that detects its own broken windows.

- A CMMS that proposes its own fixes.

- A CMMS that corrects itself with human oversight.

- A CMMS that maintains order automatically.

- A CMMS that never decays into disorder again.

This is not science fiction. It is the natural evolution of maintenance systems.

AI will not replace the human judgment required for reliability engineering, planning, or strategy, but it will eliminate the noise, the clutter and the digital disorder that prevent humans from doing their best work.

9.0 Bibliography.

1. Broken Windows: The Police and Neighborhood Safety by James Q. Wilson and George L. Kellingwikipedia

2. Fixing Broken Windows: Restoring Order And Reducing Crime In Our Communities by James Q. Wilson and George L. Kellingwikipedia

3. The Essential Guide to CMMS Software: Implementation and Best Practices by UpKeep Maintenance Teamslideshare

4. Computerized Maintenance Management Systems: A Guide to Selection and Implementation by IDCON Reliability and MaintenanceApplying-Broken-Window-Theory-to-CMMS-Master-Data-Integrity-updated.docx

5. Data Quality: The Accuracy Dimension by Jack E. OlsonApplying-Broken-Window-Theory-to-CMMS-Master-Data-Integrity-updated.docx

6. Lean Thinking: Banish Waste and Create Wealth in Your Corporation by James P. Womack and Daniel T. JonesApplying-Broken-Window-Theory-to-CMMS-Master-Data-Integrity-updated.docx

7. Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production by Taiichi OhnoApplying-Broken-Window-Theory-to-CMMS-Master-Data-Integrity-updated.docx

8. Behavioral-Based Safety: A Proven Approach to Safety Management by E. Scott GellerApplying-Broken-Window-Theory-to-CMMS-Master-Data-Integrity-updated.docx

9. 5S for Operators: 5 Pillars of the Visual Workplace by Hiroyuki HiranoApplying-Broken-Window-Theory-to-CMMS-Master-Data-Integrity-updated.docx

10. Class A: The Benchmark for World-Class Operations by David BukerApplying-Broken-Window-Theory-to-CMMS-Master-Data-Integrity-updated.docx

11. Asset Management Excellence: Making Smart Investment Decisions by John D. Campbell et al.Applying-Broken-Window-Theory-to-CMMS-Master-Data-Integrity-updated.docx

12. Reliability-Centered Maintenance by John MoubrayApplying-Broken-Window-Theory-to-CMMS-Master-Data-Integrity-updated.docx

13. The Intelligent Asset Manager: The Key to World-Class Maintenance by Gary CokinsApplying-Broken-Window-Theory-to-CMMS-Master-Data-Integrity-updated.docx

14. Big Data and Analytics for Maintenance Optimization by IBM Maximo TeamApplying-Broken-Window-Theory-to-CMMS-Master-Data-Integrity-updated.docx

15. AI in Maintenance Management: Transforming CMMS by UpKeep AI InsightsApplying-Broken-Window-Theory-to-CMMS-Master-Data-Integrity-updated.docx

16. Broken Windows Theory by Wikipedia Contributorswikipedia

17. Broken Windows Theory in Criminology by Saul McLeodsimplypsychology

18. Broken Windows Theory: Definition and Effects by Study.com Editorsstudy

19. The Broken Window Theory in Software Development by Jeff Atwoodcodinghorror

20. Broken Windows Theory in Community Management by Valley East Today Groupfacebook

21. How Broken Windows Policing Works by Britannica Editorsbritannica

22. Broken Windows in Software Maintenance by Tushar Sharma et al.tusharma

23. CMMS Data Quality Best Practices by UpKeep BlogApplying-Broken-Window-Theory-to-CMMS-Master-Data-Integrity-updated.docx

24. Zero Tolerance for Data Defects in Asset Management by Maintworld EditorsApplying-Broken-Window-Theory-to-CMMS-Master-Data-Integrity-updated.docx

25. Behavioral Safety and Maintenance Culture by Reliable PlantApplying-Broken-Window-Theory-to-CMMS-Master-Data-Integrity-updated.docx

26. 5S Implementation in Maintenance by Lean Production TeamApplying-Broken-Window-Theory-to-CMMS-Master-Data-Integrity-updated.docx

27. Buker Business Excellence in CMMS by Buker InternationalApplying-Broken-Window-Theory-to-CMMS-Master-Data-Integrity-updated.docx

28. AI-Driven Data Governance in CMMS by IBM Watson TeamApplying-Broken-Window-Theory-to-CMMS-Master-Data-Integrity-updated.docx

29. Preventing Data Decay in Enterprise Systems by Gartner AnalystsApplying-Broken-Window-Theory-to-CMMS-Master-Data-Integrity-updated.docx

[…] 3. Once you’re okay with one piece of damage to your car, it’s possible that you’ll end up being okay with two, three, or more pieces of damage over time, and before you know it, your car is a shambles. This phenomenon is sometimes referred to as the broken window theory and there’s an article on this here. […]

[…] Broken Windows Theory – Maintenance Systems Effectiveness. Broken window theory. Analyse maint2. Analyse maintenance performance. Execute & Complete Maintenance Work – CMMS SUCCESS. Execute and Complete Maintenance Work. Get the most out of your Assets – CMMS SUCCESS. Get the most out of our assets. Your boss needs solutions not problems – CMMS SUCCESS. Dealing with complaints at work. Asset Management Training for Mainteannce Planners. Asset Management Training for Planners – CMMS SUCCESS. Operations Run down and Start up Plans. […]

[…] Broken Window Theory, when applied to asset management and your CMMS, highlights the significance of timely repairs, preventive maintenance and data […]