Identifying Heroic Load Syndrome And Dealing With It

Disclaimer.

This article provides general guidance on organizational management, leadership practices and maintenance system design.

It does not constitute professional advice specific to your organization’s legal, regulatory, or operational requirements.

Readers should consult qualified professionals regarding compliance obligations, workplace health and safety matters and system implementation decisions relevant to their specific circumstances.

Opinions, views, thoughts and ideas expressed are those of the author only.

Article Summary.

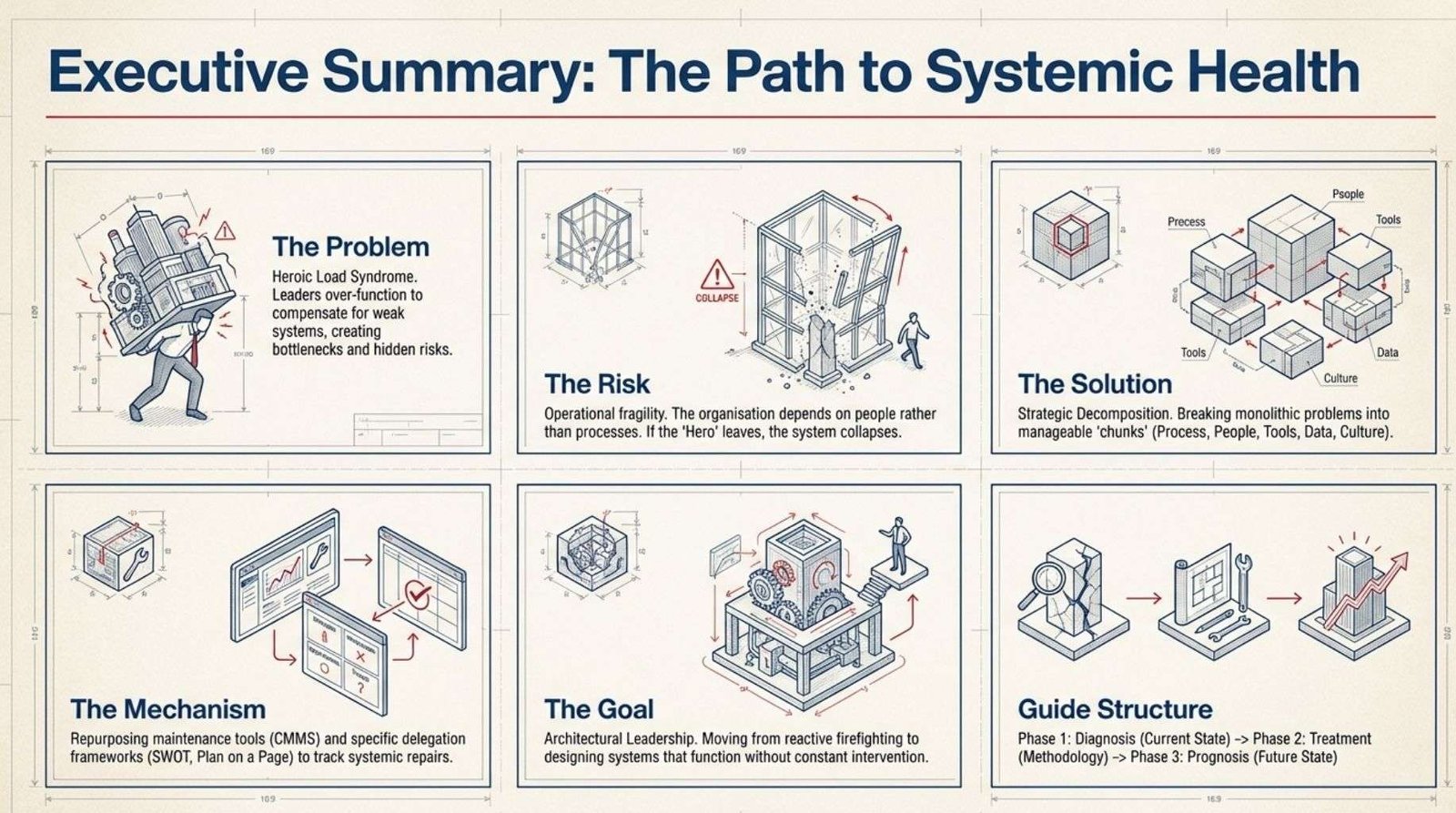

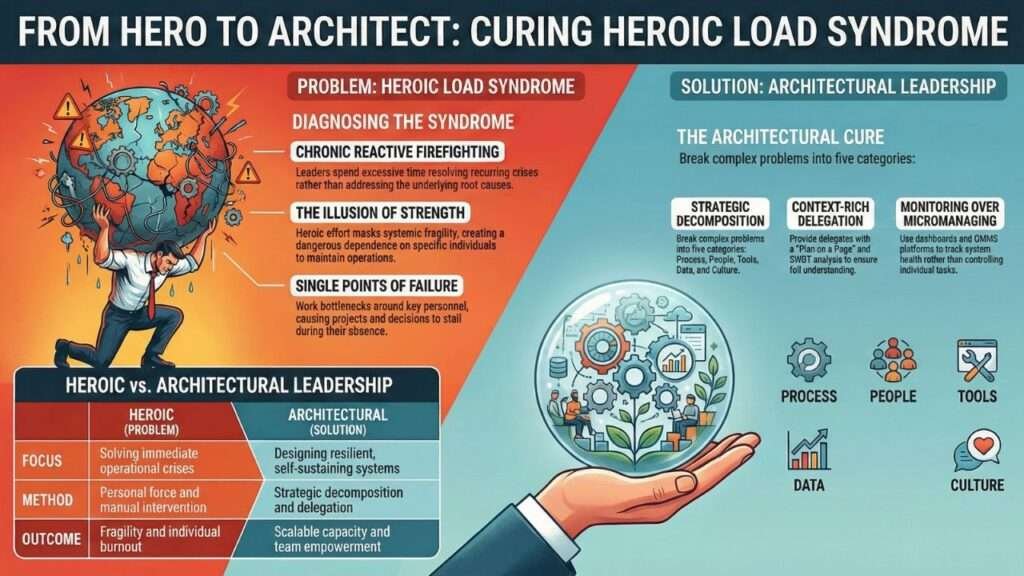

Heroic Load Syndrome describes a pattern where leaders over-function to compensate for weak organizational systems, creating unsustainable operational models dependent on individual effort rather than systematic design.

This condition manifests through chronic firefighting, bottlenecks around key personnel and hidden compliance risks masked by reactive workarounds.

The syndrome stems from fragmented processes, inadequate documentation and systems that require constant manual intervention rather than functioning reliably on their own.

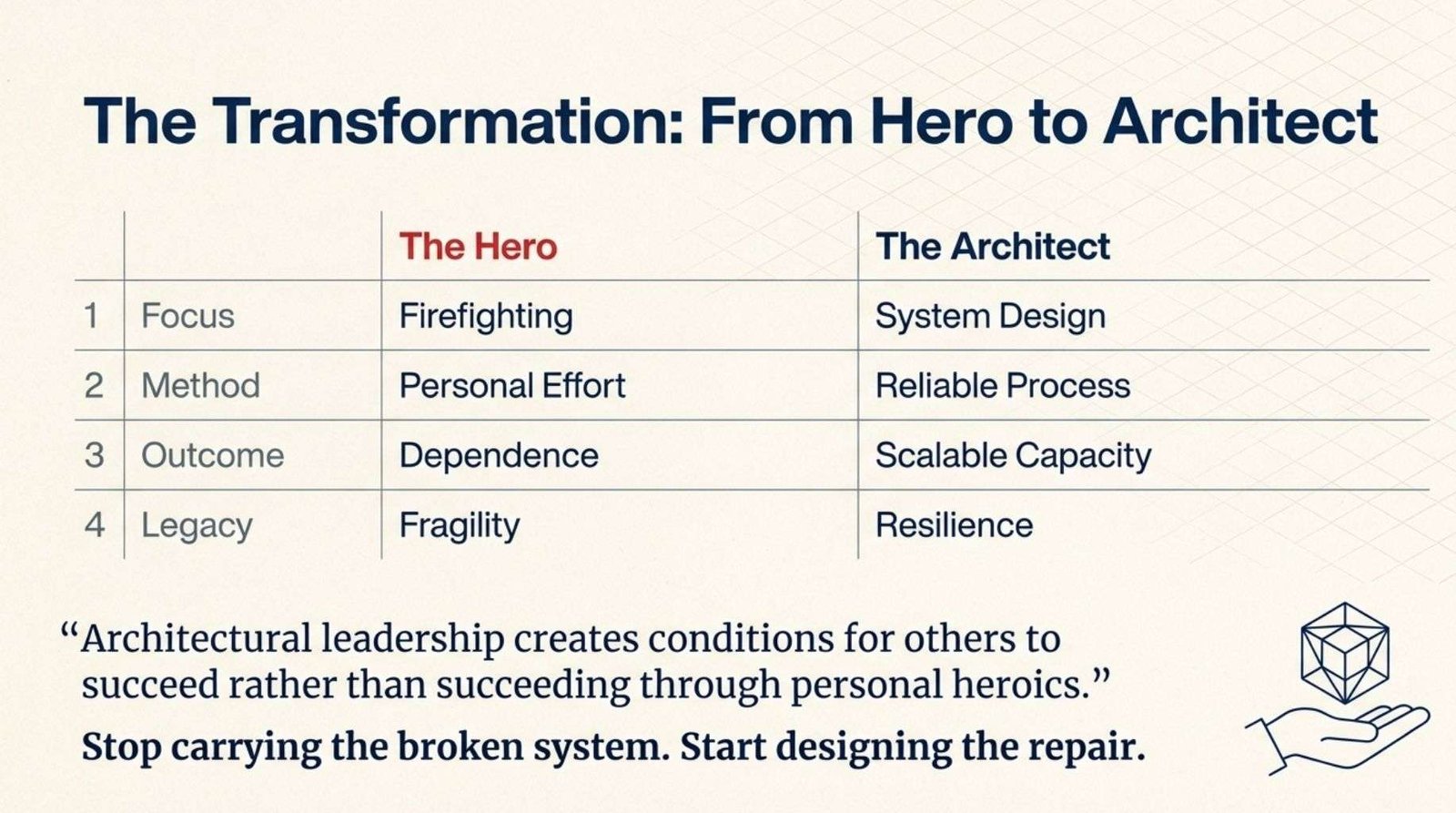

This article examines how leaders can transition from bearing organizational burden through personal effort to designing resilient systems that operate effectively without constant intervention.

Using maintenance management and CMMS platforms as practical examples, it demonstrates how breaking complex systemic problems into manageable components, assigning clear ownership with full context and leveraging existing tools for non-traditional purposes enables sustainable organizational improvement.

The shift from heroic individual effort to architectural leadership creates scalable capacity and reduces organizational dependence on any single person.

Top 5 Takeaways.

1. Heroic Load Syndrome occurs when leaders compensate for broken systems through unsustainable personal effort, creating bottlenecks and masking underlying organizational weaknesses that require systematic solutions.

2. Strategic decomposition involves breaking complex systemic problems into categories such as Process, People, Tools, Data and Culture, making previously overwhelming challenges manageable and actionable.

3. CMMS platforms can track systemic improvement work beyond traditional maintenance tasks by creating work request types for governance gaps, training rollouts, documentation projects and process standardization efforts.

4. Effective delegation requires providing full context through tools like SWOT analysis and plan-on-a-page documents rather than simply assigning tasks, enabling team members to understand both the problem and the intended solution pathway.

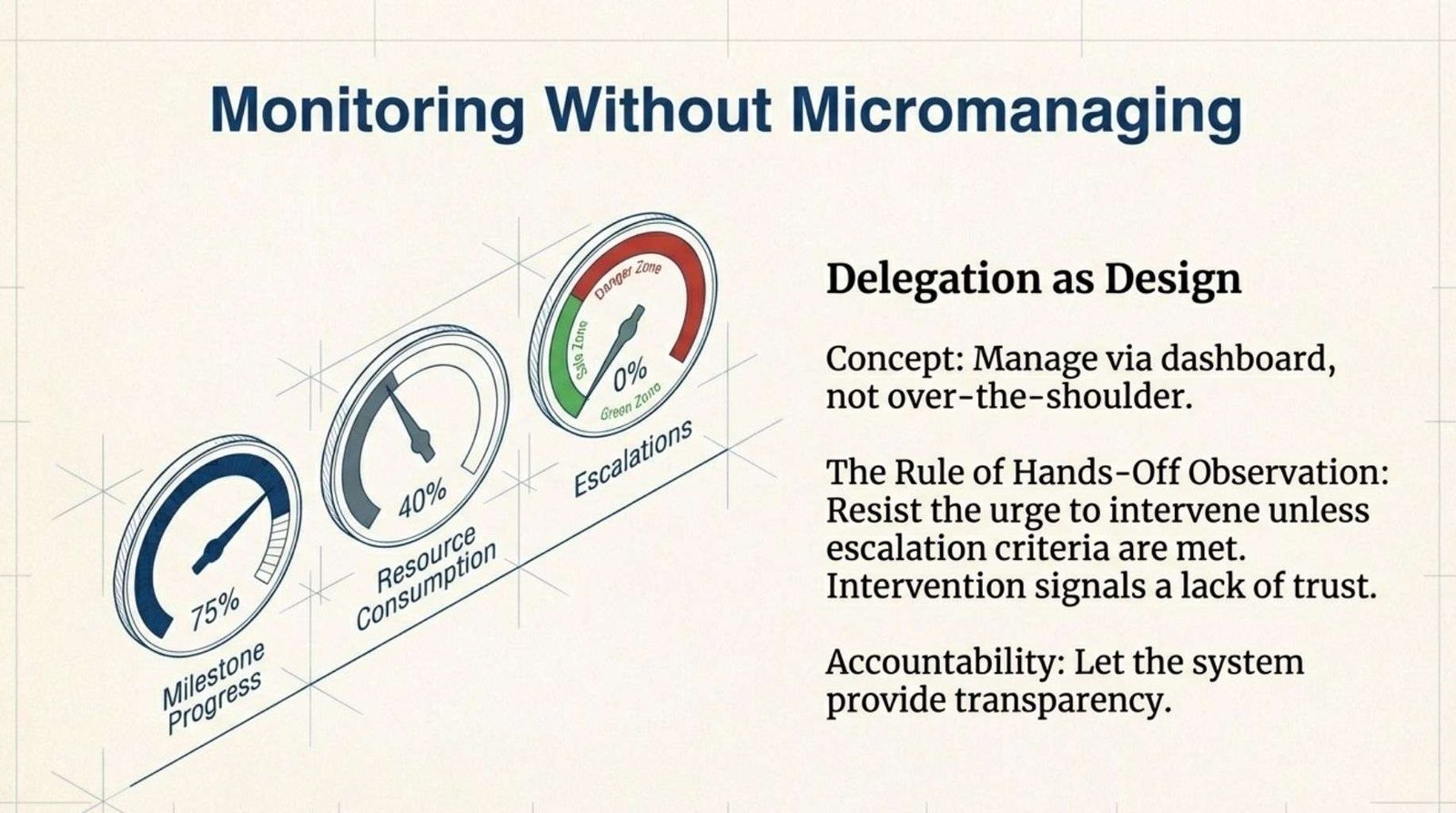

5. Monitoring systems rather than micromanaging people allows leaders to track progress through dashboards and status updates while empowering teams to own their assigned components of systemic improvement.

Table of Contents.

1.0 Introduction: Diagnosing Heroic Load Syndrome.

2.0 Symptoms of Heroic Load Syndrome.

3.0 The Compliance Connection.

4.0 The Maintenance Management Parallel.

5.0 Breaking the Burden: Strategic Decomposition.

6.0 Chunk Taxonomy: Naming the Invisible.

7.0 Plan on a Page: The Clarity Catalyst.

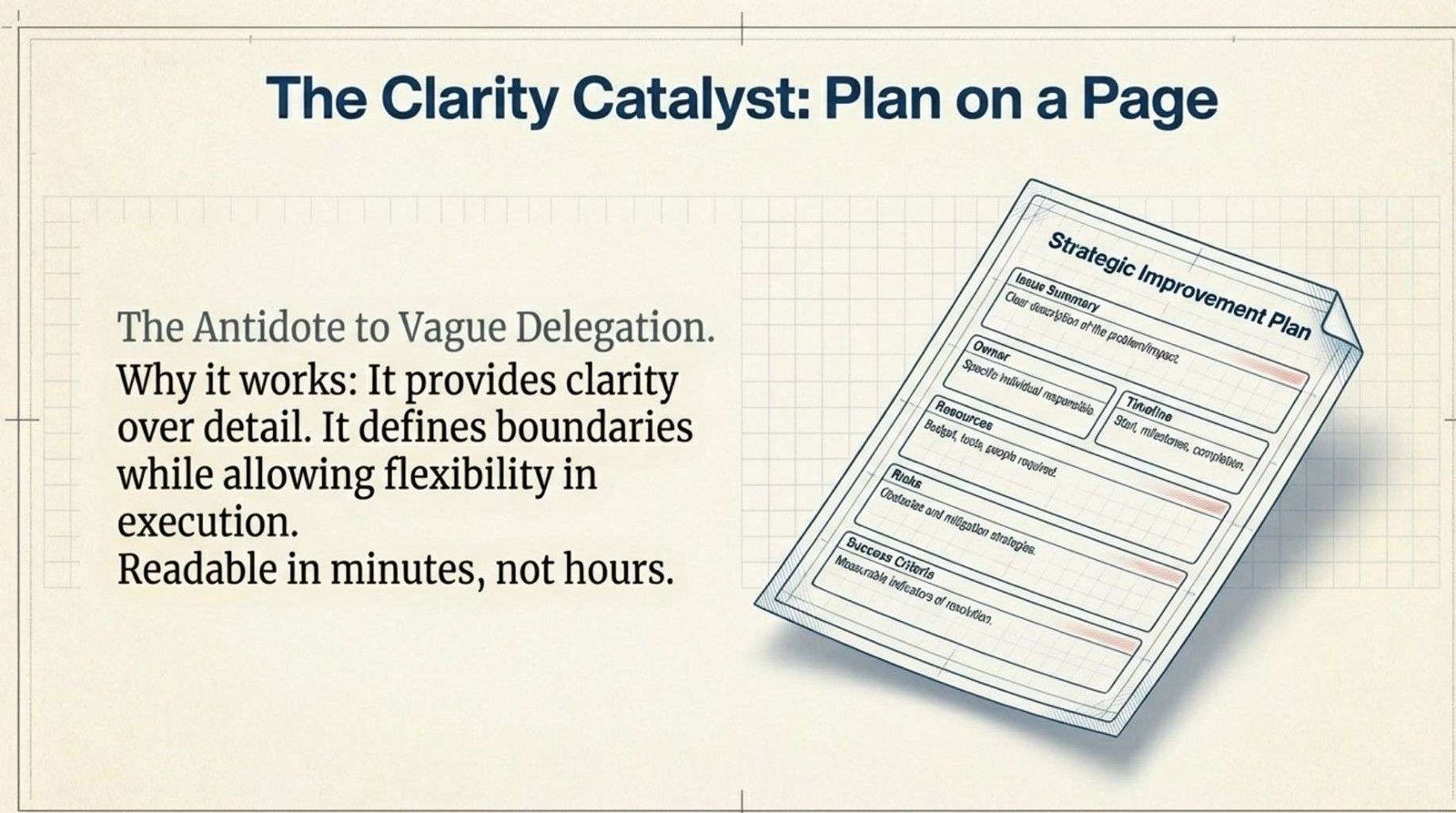

8.0 SWOT Analysis: Empowering the Delegate.

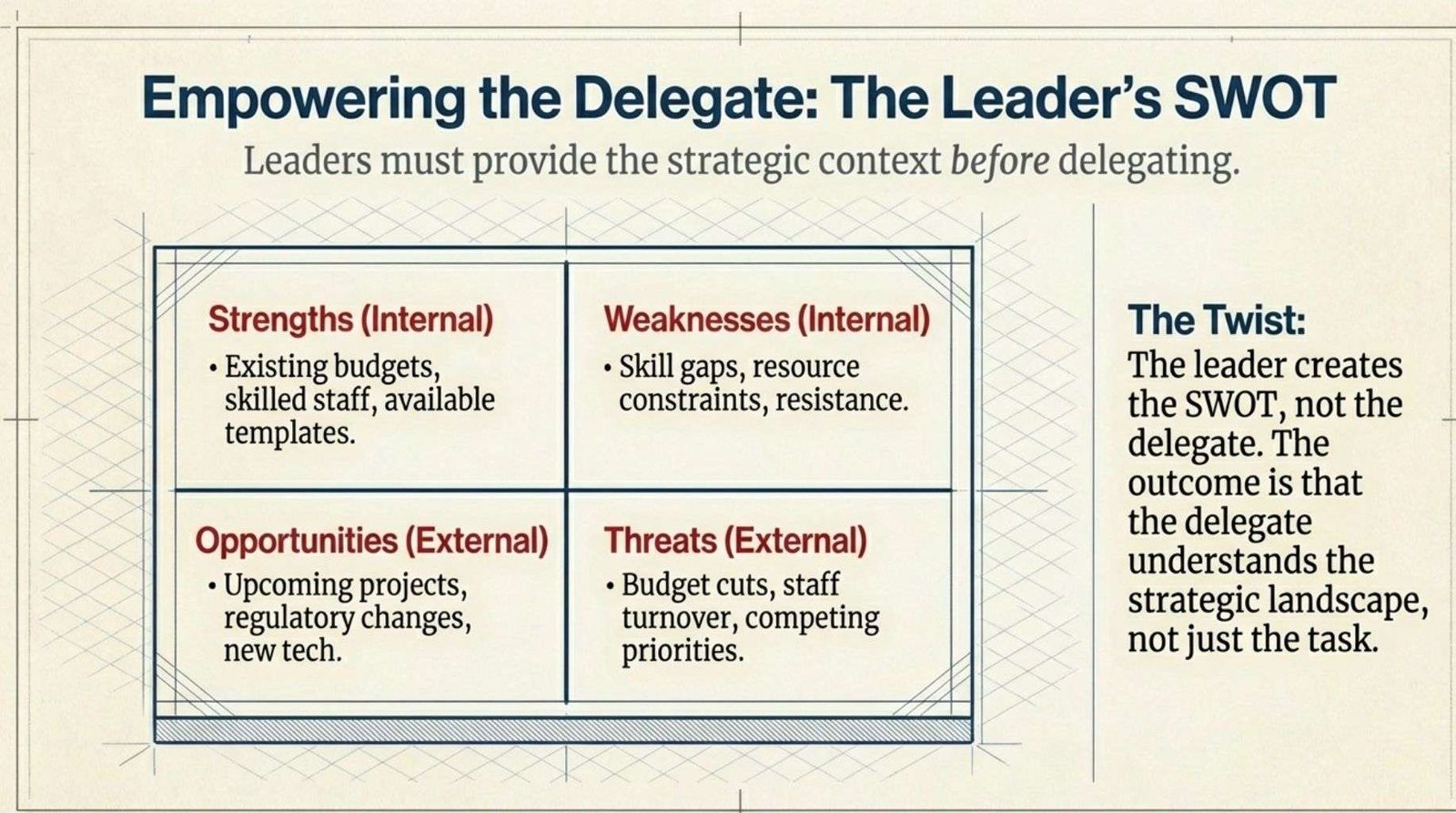

9.0 Delegation as Design.

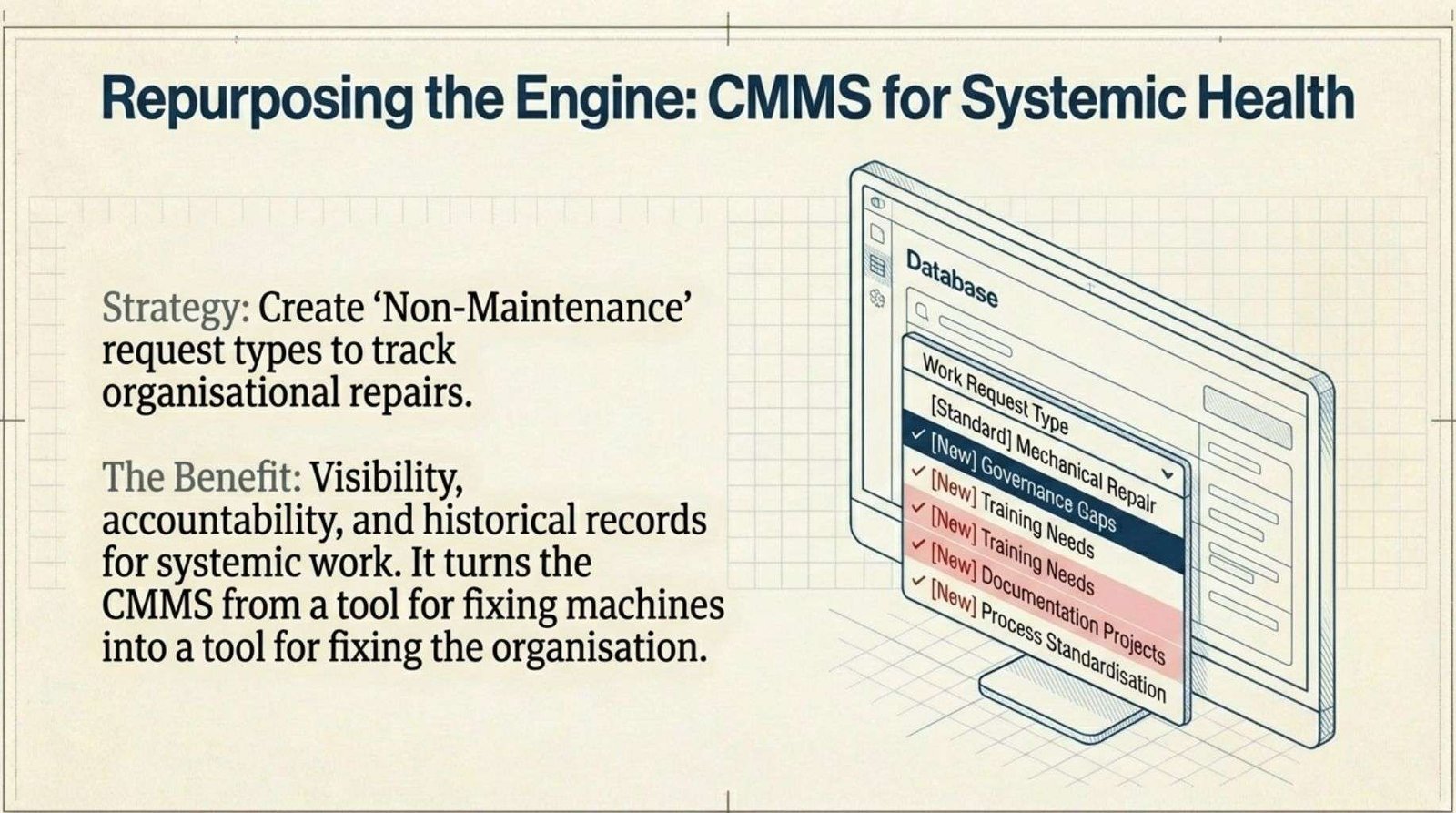

10.0 Using CMMS for Systemic Issues.

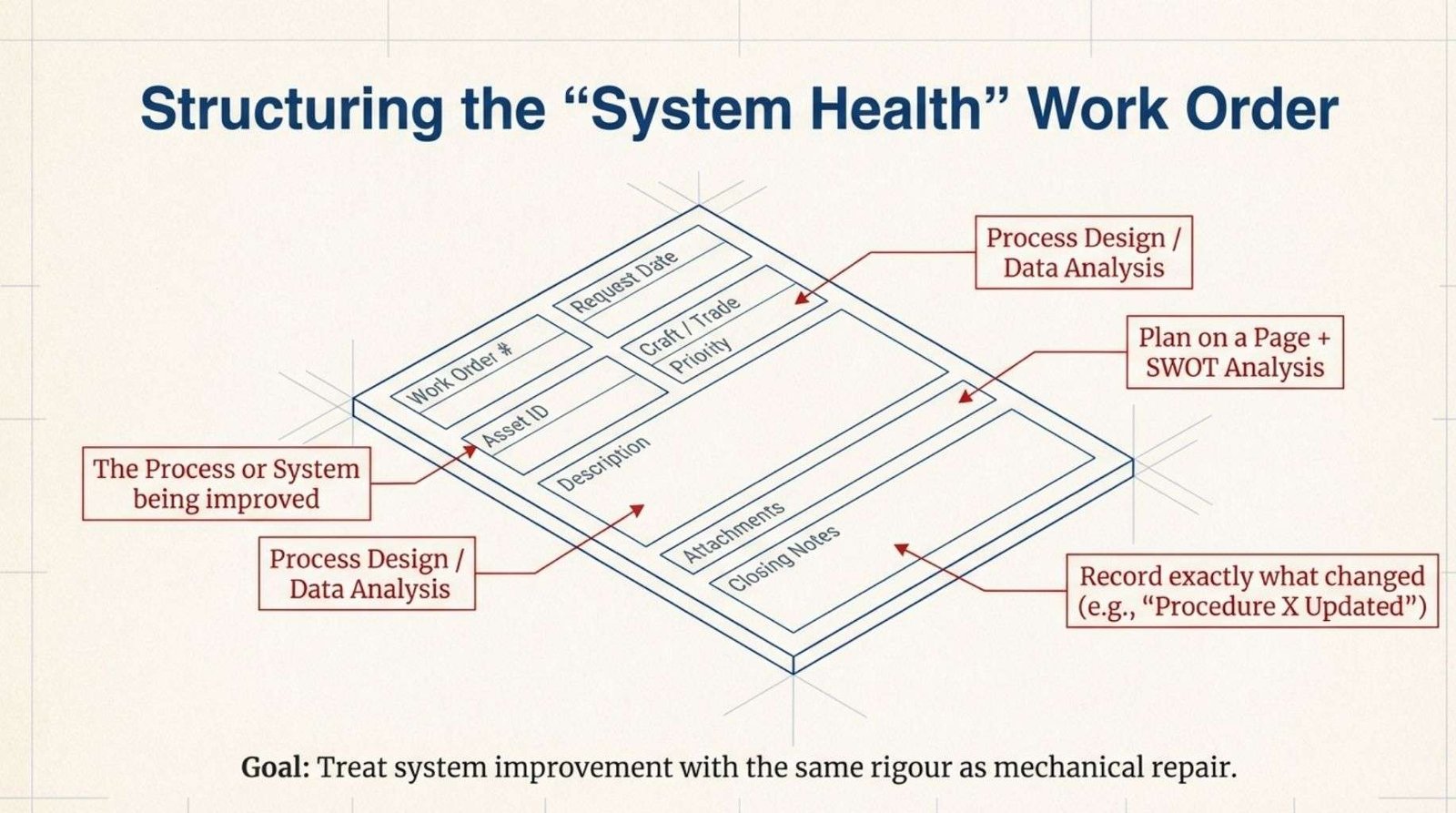

11.0 Structuring Work Orders for System Health.

12.0 Monitoring Without Micromanaging.

13.0 Closing the Loop: Recognition and Learning.

14.0 From Hero to Architect.

15.0 Conclusion: Cure the Syndrome, Elevate the System.

16.0 Bibliography.

1.0 Introduction: Diagnosing Heroic Load Syndrome.

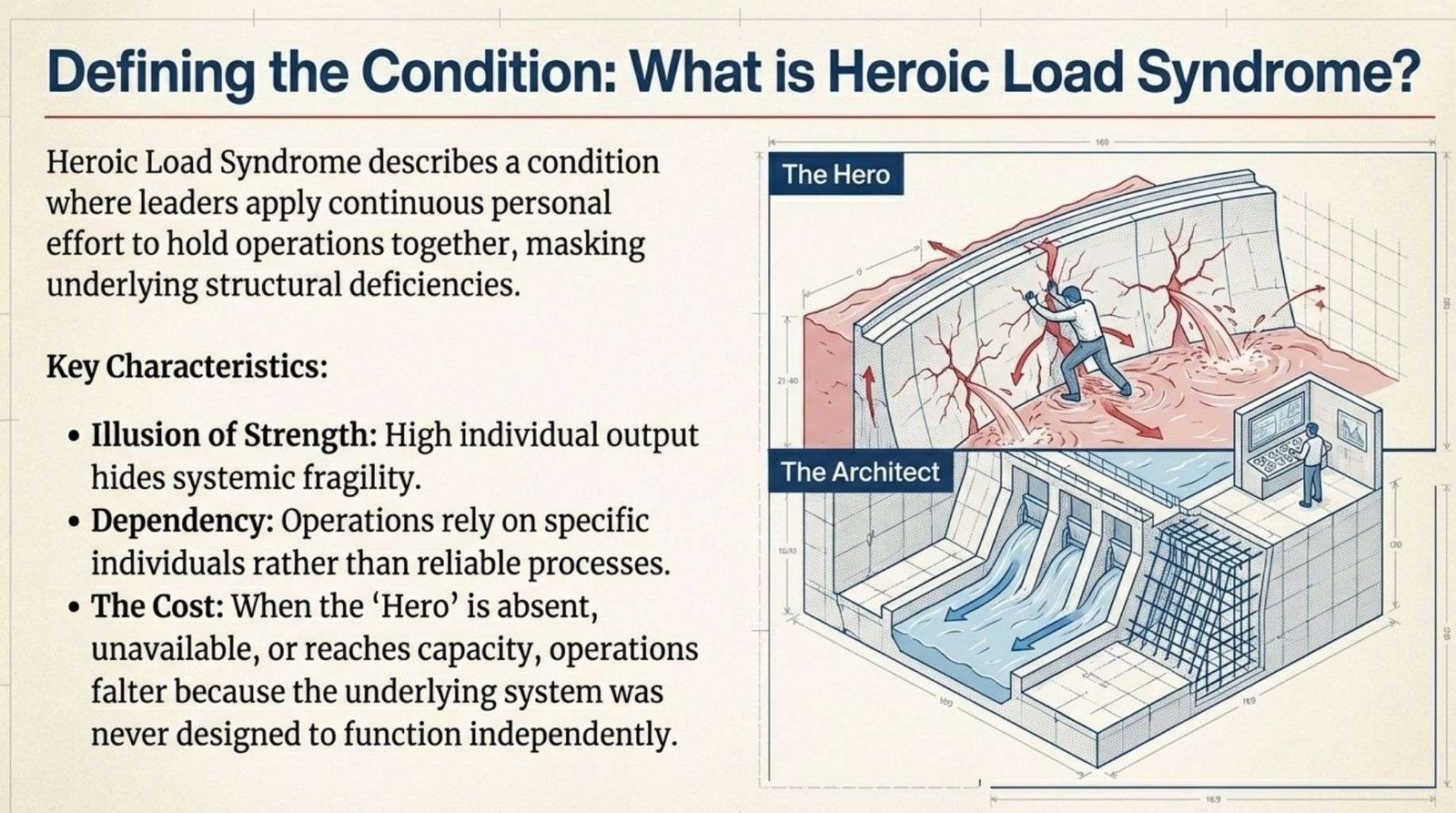

Heroic Load Syndrome describes an organizational condition in which leaders over‑function to compensate for weak or immature systems.

Instead of addressing structural deficiencies, they rely on continuous personal effort to keep operations intact.

This creates the illusion that “everything is fine” while concealing both the leader’s exhaustion and the volume of unresolved problems caused by systemic fragility and poor-quality processes.

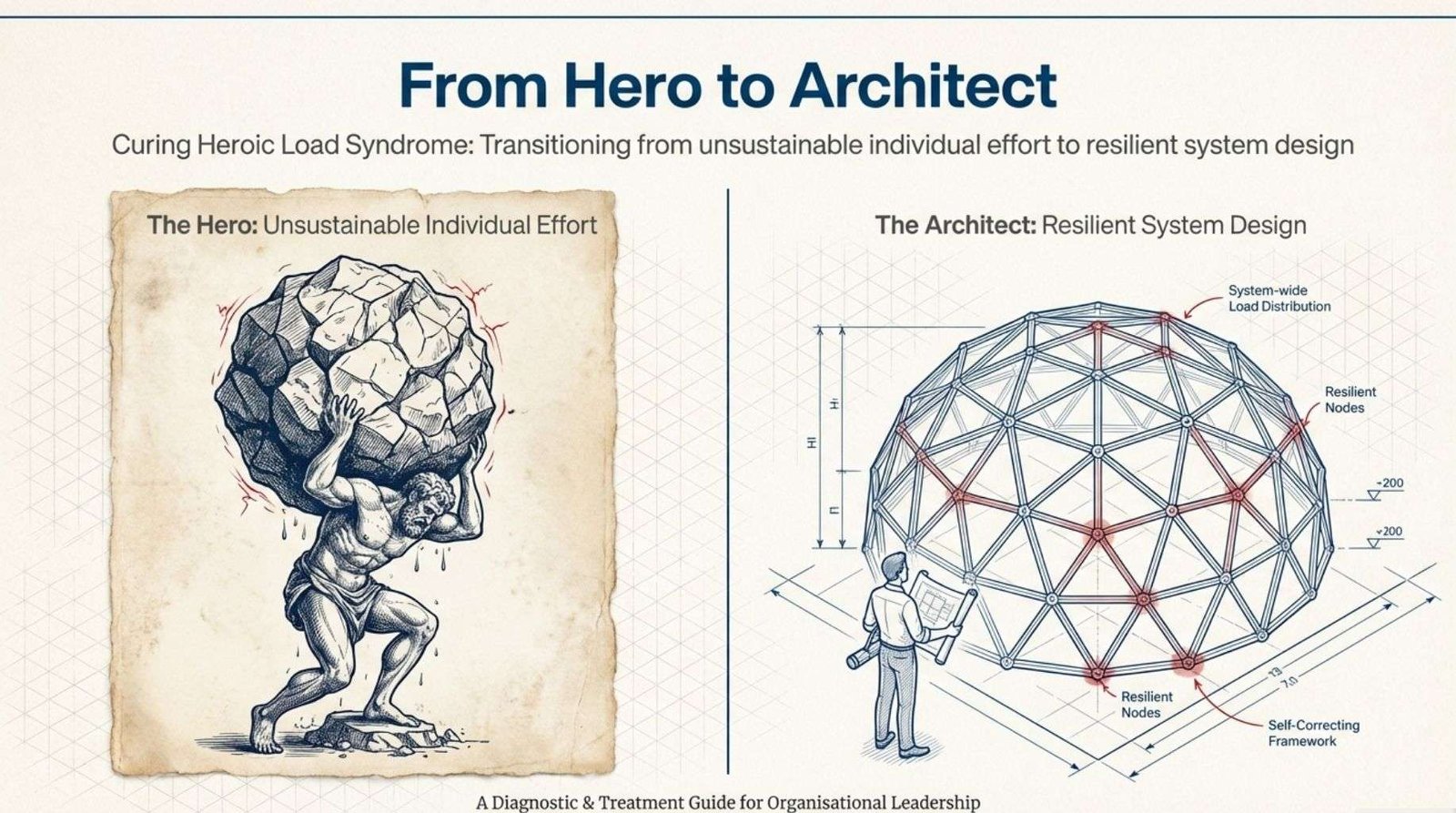

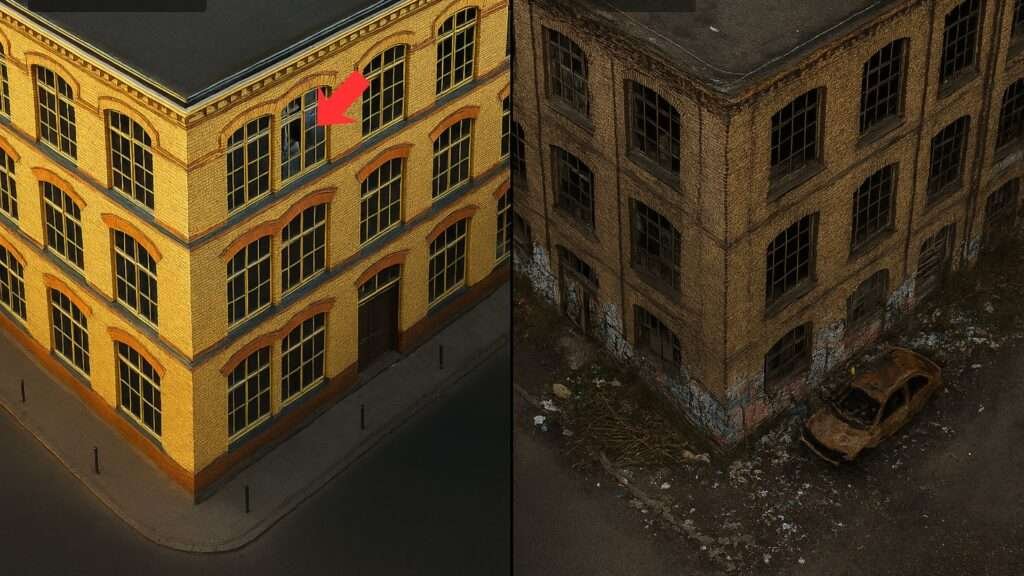

The syndrome is captured vividly in two contrasting images: a muscular figure straining to hold up an entire world, and an open palm supporting a small, manageable sphere.

The first symbolizes the leader attempting to carry organizational weight through sheer force. The second represents strategic decomposition, the discipline of breaking complexity into components that can be managed systematically rather than heroically.

Organizations caught in this pattern become dependent on specific individuals instead of reliable processes.

When those individuals are absent, unavailable, or reach their capacity limits, operations falter. The cycle persists because the underlying systems never receive the attention, investment, or redesign required to function independently.

This article explores how leaders can recognize Heroic Load Syndrome, understand its organizational and personal costs, and shift from carrying the load themselves to designing systems that distribute it intelligently across processes, tools, and empowered teams.

2.0 Symptoms of Heroic Load Syndrome.

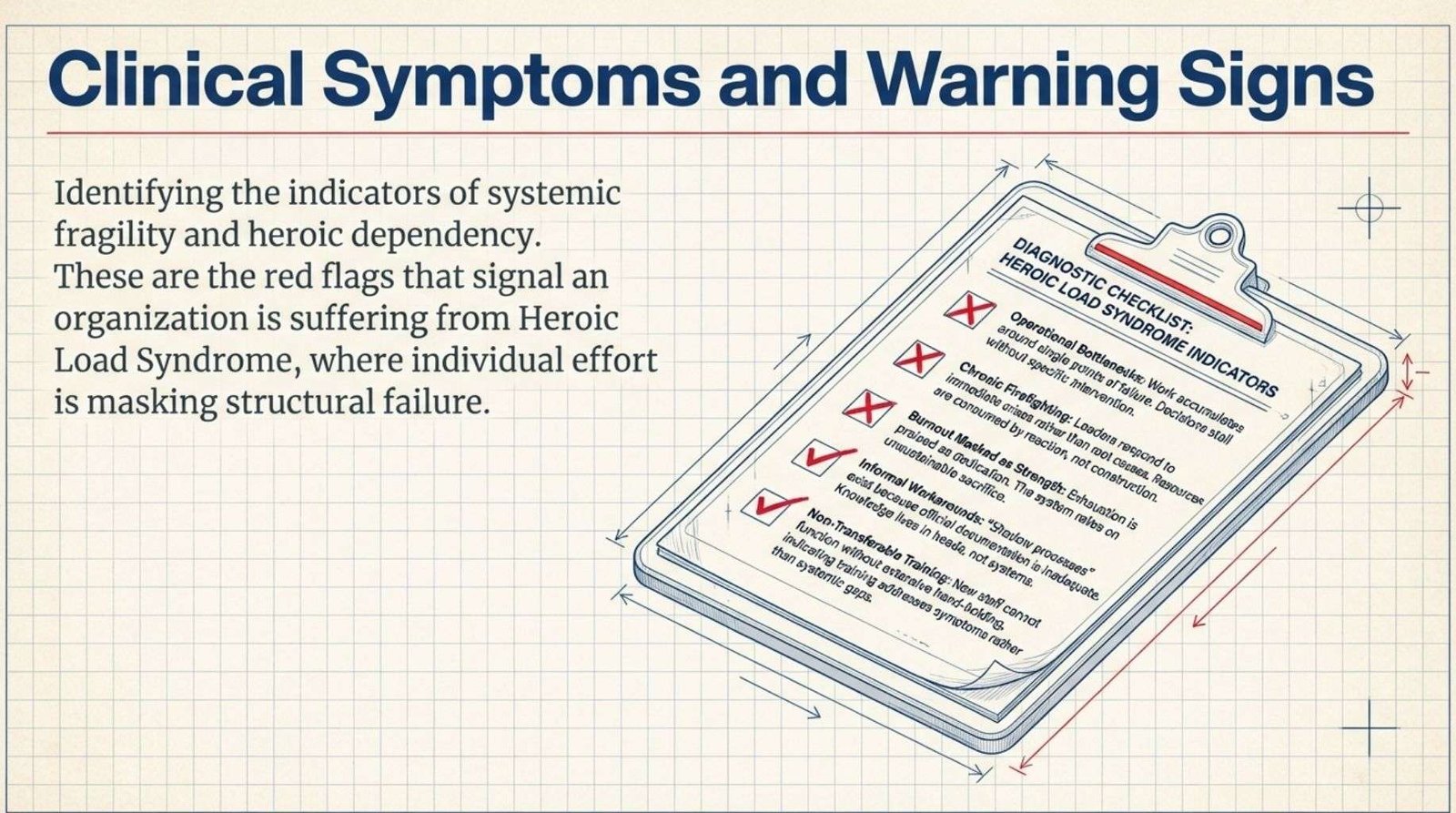

Heroic Load Syndrome produces identifiable symptoms at both organizational and individual levels.

Recognition of these patterns enables targeted intervention.

2.1. Operational Bottlenecks.

Work accumulates around specific individuals who become single points of failure. Decisions await their input.

Problems remain unresolved until they intervene.

Projects stall during their absence.

The organization has created dependencies on heroic individuals rather than building capacity into systems and teams.

2.2. Chronic Reactive Firefighting.

Leaders spend most of their time responding to immediate crises rather than addressing root causes.

The same problems recur because underlying systems remain unrepaired.

Firefighting becomes the norm, consuming resources that could otherwise strengthen organizational infrastructure.

2.3. Burnout Masked as Strength.

Emotional and physical exhaustion appears as dedication or capability. Leaders work excessive hours, skip breaks and maintain unsustainable pace.

Organizations reward this behavior, reinforcing the pattern. The individual suffers while the system remains dependent on their continued sacrifice.

2.4. Informal Workarounds.

Official processes exist but prove inadequate. Staff develop informal methods to accomplish work.

These workarounds function only because specific people know them. Knowledge remains undocumented.

New staff struggle because formal systems provide insufficient guidance.

2.5. Training That Does Not Transfer.

Training programs exist but graduates cannot apply learning without extensive additional support.

This indicates that training addresses symptoms rather than systemic gaps. Procedures may be documented but incomplete, unclear, or disconnected from actual workflow requirements.

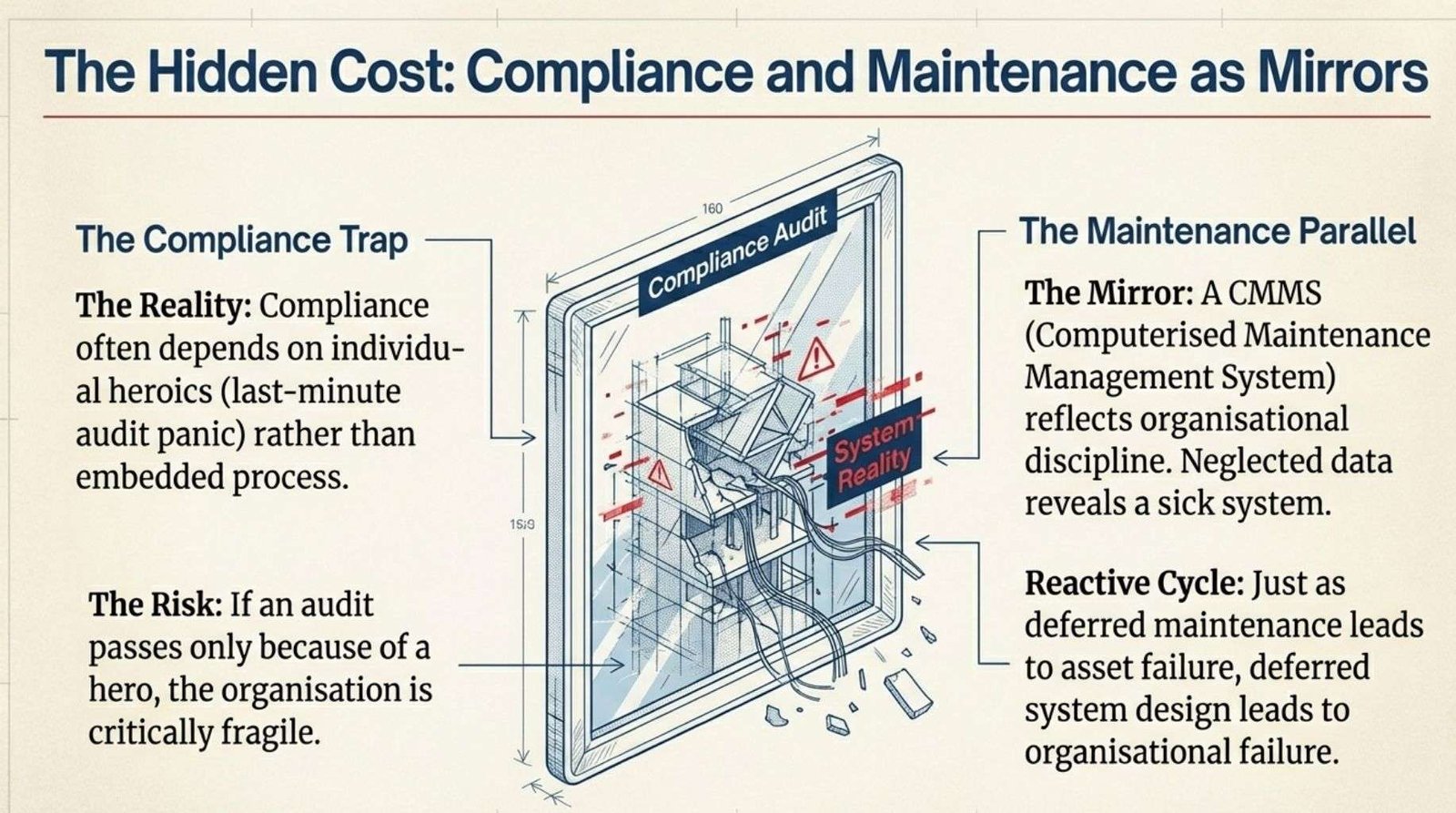

3.0 The Compliance Connection.

Fragmented systems create invisible compliance risks that heroic effort temporarily masks but cannot permanently resolve.

3.1. Compliance as System Health Indicator.

Compliance requirements reveal whether organizational systems function reliably. When compliance depends on individual effort rather than embedded processes, the organization operates in a fragile state. Audits may pass due to last-minute heroics, but underlying capability remains weak.

3.2. Discipline, Governance and Culture.

Effective compliance stems from discipline in following processes, governance structures that ensure accountability and culture that values systematic approaches over improvisation. Rules alone prove insufficient. Organizations require systems that make compliance the natural outcome of standard work rather than an additional burden requiring special effort.

3.3. Hidden Risks in Workarounds.

When staff bypass official processes, organizations lose visibility into actual practices.

This creates compliance exposure. Documentation does not reflect reality. Auditors see procedures; operations use different methods.

The gap between documented and actual practice represents unmanaged risk.

3.4. Heroic Effort as Compliance Barrier.

Leaders who personally ensure compliance prevent systems from developing necessary capabilities.

Their intervention demonstrates that processes cannot independently produce compliant outcomes. This dependence becomes visible only when the heroic individual is unavailable.

4.0 The Maintenance Management Parallel.

Computerized Maintenance Management Systems function as diagnostic tools, revealing organizational health through how they are used or neglected.

4.1. CMMS as System Mirror.

A CMMS reflects organizational discipline. When used properly, it demonstrates that processes exist, staff follow them and leadership monitors outcomes.

When neglected, it reveals that systems are weak, documentation is poor and operations depend on informal knowledge rather than structured approaches.

4.2. Common Failure Modes.

Asset-intensive environments exhibit predictable patterns when suffering from Heroic Load Syndrome:

1. Work orders created after tasks complete, serving only as records rather than planning tools.

2. Preventive maintenance schedules ignored because reactive work consumes all capacity.

3. Data quality poor because staff lack time or training to enter information accurately.

4. Reports unused because leadership lacks processes to act on insights.

5. System perceived as administrative burden rather than operational asset.

4.3. Maintenance Planning Breakdown.

When planners and supervisors spend their time firefighting, planned maintenance degrades into reactive response.

Schedules slip. Preventive work is deferred. Assets deteriorate faster. Failures increase. This creates more reactive work, perpetuating the cycle.

4.4. Knowledge Retention Failure.

Heroic individuals possess extensive undocumented knowledge. When they leave, that knowledge disappears. CMMS platforms can capture and preserve this knowledge through structured documentation, but only if organizations invest in building that capability systematically rather than depending on individual memory.

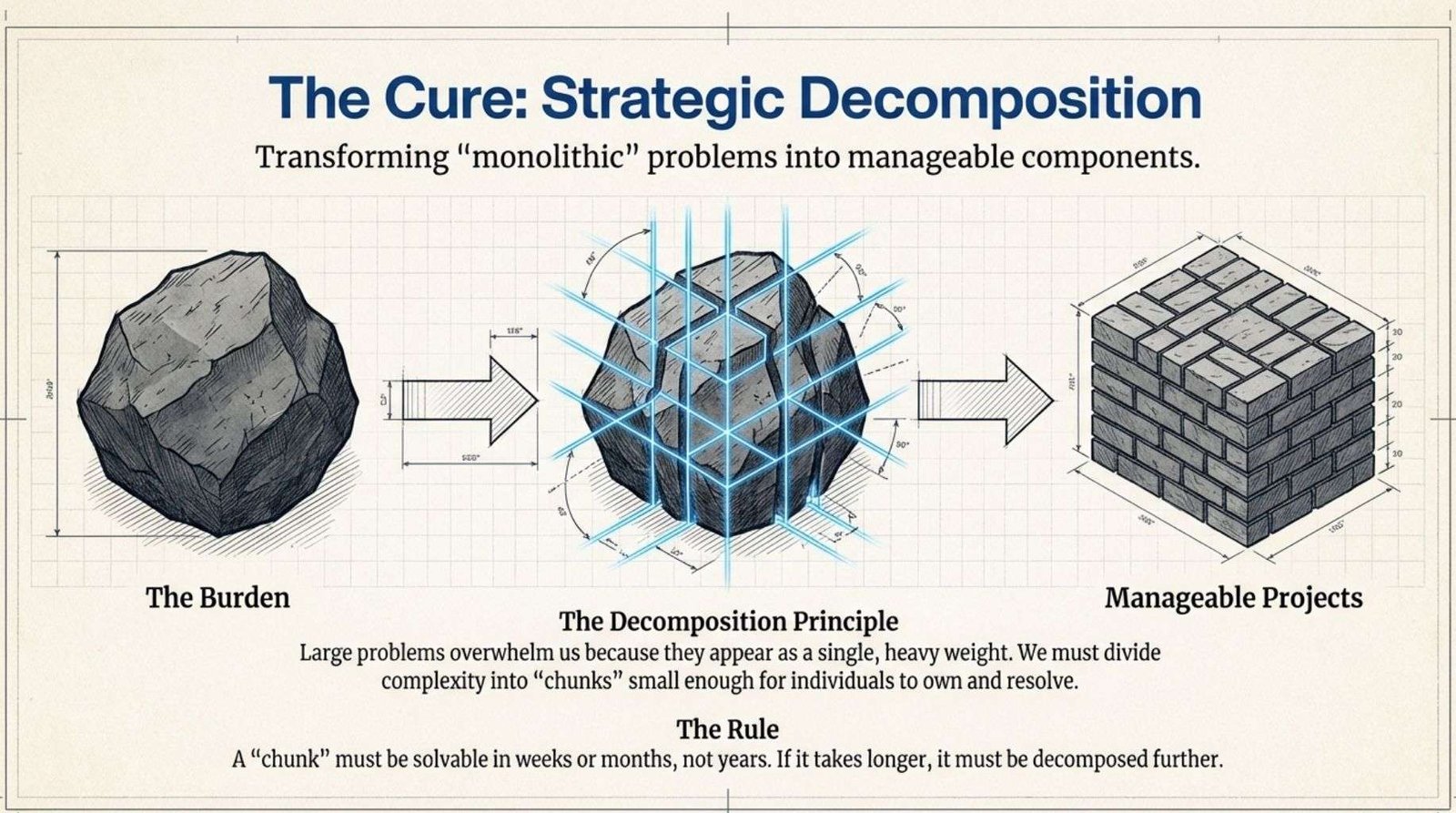

5.0 Breaking the Burden: Strategic Decomposition.

Complex systemic problems become manageable when broken into discrete components that can be addressed independently.

5.1. The Decomposition Principle.

Large problems overwhelm because they appear monolithic.

Strategic decomposition divides complexity into chunks small enough for individuals or small teams to own and resolve. This transforms an impossible burden into a portfolio of achievable projects.

5.2. Standard Categories for Decomposition.

Organizing problems into categories provides structure for analysis:

1. Process: Workflows, procedures, approval chains, handoffs, decision criteria.

2. People: Skills, training, roles, responsibilities, capacity, workload distribution.

3. Tools: Software, equipment, templates, reference materials, communication platforms.

4. Data: Quality, accessibility, structure, documentation, reporting, analysis capability.

5. Culture: Norms, behaviors, accountability mechanisms, recognition systems, communication patterns.

5.3. Preventing Category Overlap.

Some problems span multiple categories. Assign each chunk to its primary category while noting dependencies.

This prevents duplication and clarifies which team or function should lead resolution.

5.4. Sizing Chunks Appropriately.

Each chunk should be small enough for one person or team to complete within a defined timeframe, typically weeks or months rather than years.

If a chunk requires longer duration, decompose it further.

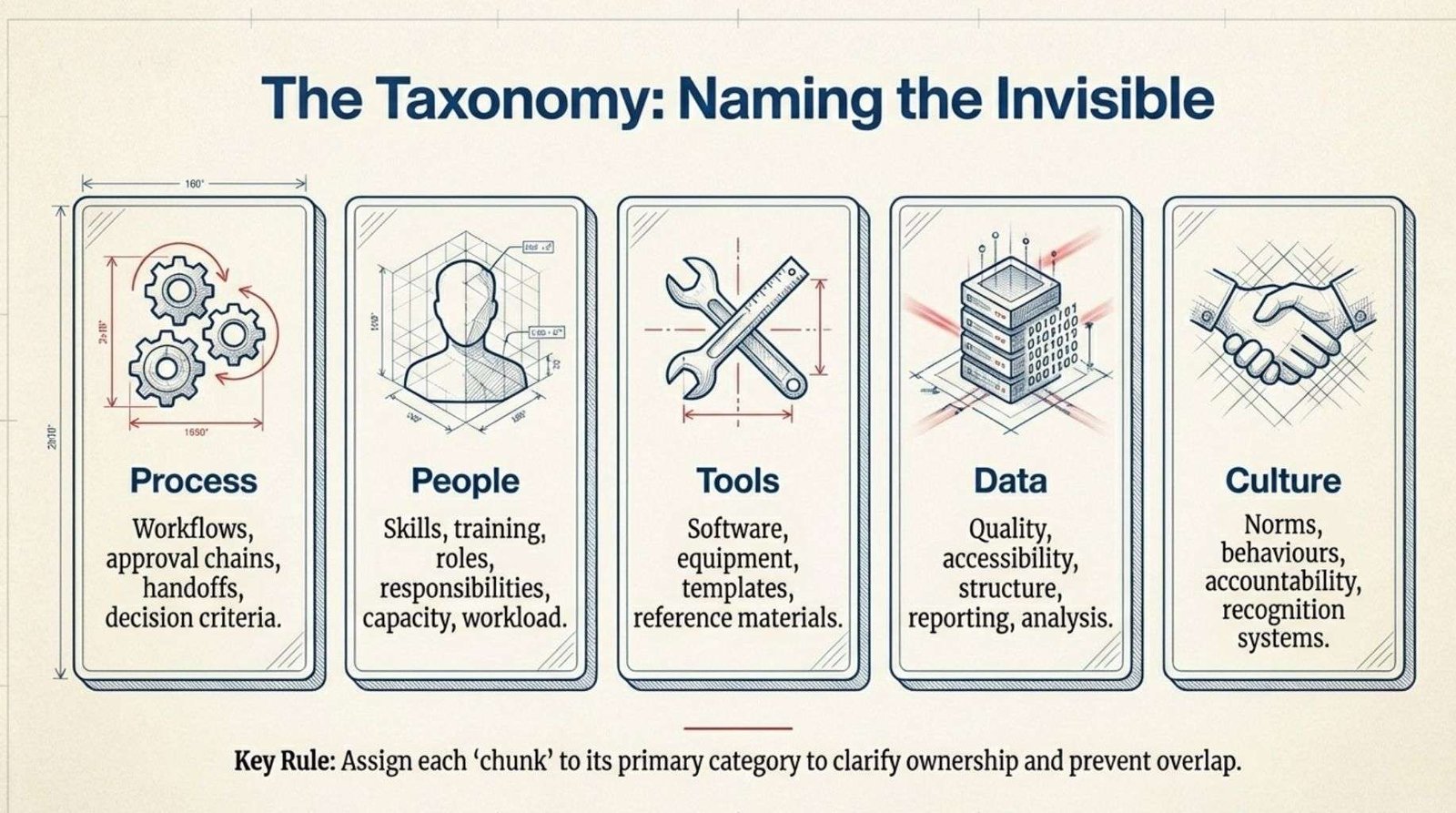

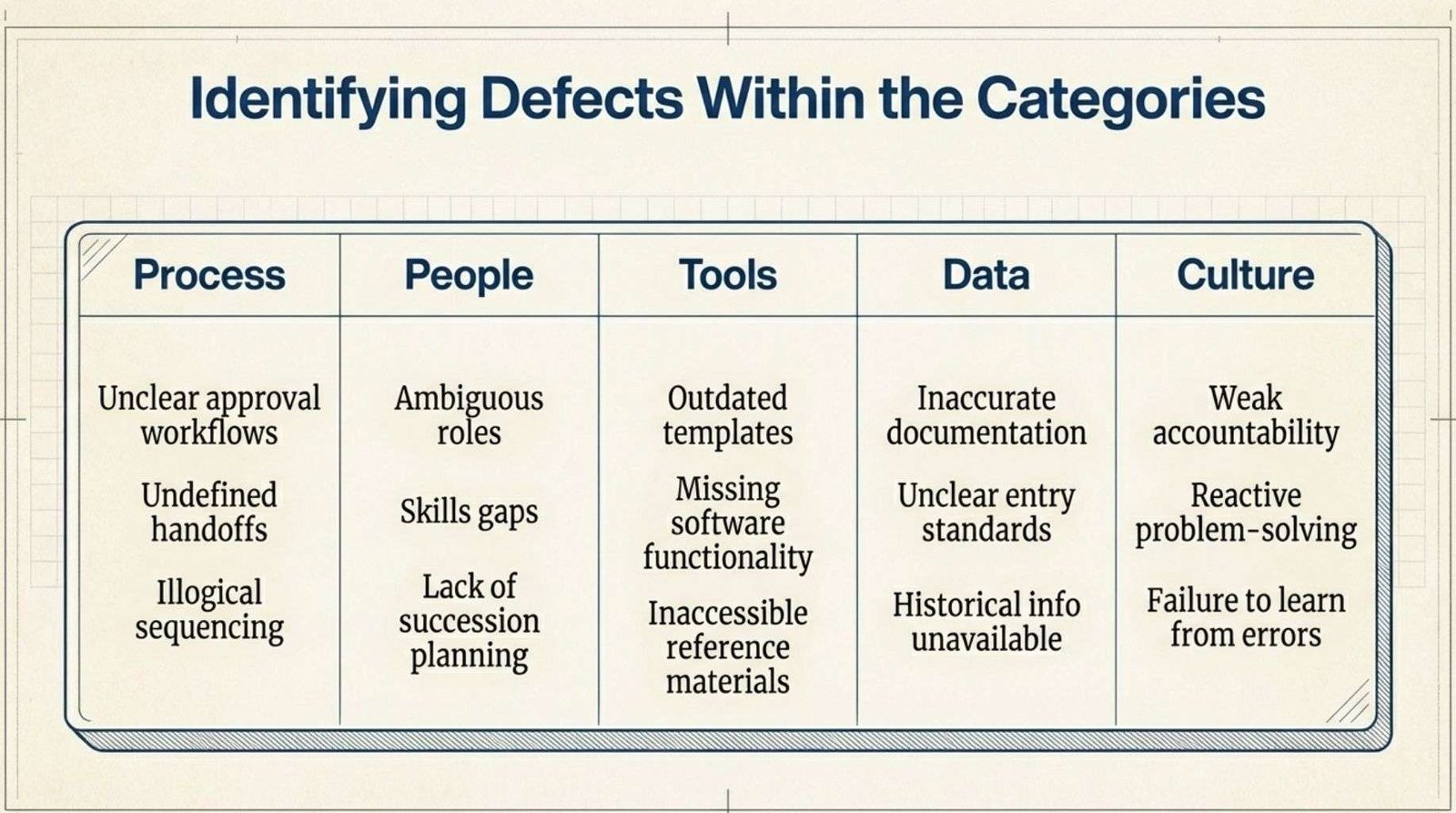

6.0 Chunk Taxonomy: Naming the Invisible.

Creating a structured list of systemic defects makes previously invisible problems concrete and actionable.

6.1. Identification Process.

List all known systemic weaknesses without initial filtering.

Include problems that cause recurring issues, require workarounds, generate complaints, consume excessive time, or create quality defects.

6.2. Process Defects.

Examples include:

1. Procedures missing for critical tasks.

2. Approval workflows unclear or inconsistent.

3. Handoffs between departments poorly defined.

4. Decision criteria undocumented.

5. Work sequencing illogical or inefficient.

6.3. People Defects.

Examples include:

1. Training inadequate for job requirements.

2. Roles and responsibilities ambiguous.

3. Skills gaps unaddressed.

4. Workload distribution uneven.

5. Succession planning absent.

6.4. Tool Defects.

Examples include:

1. Software missing required functionality.

2. Templates outdated or incomplete.

3. Reference materials inaccessible.

4. Communication platforms ineffective.

5. Equipment unreliable or insufficient.

6.5. Data Defects.

Examples include:

1. Documentation incomplete or inaccurate.

2. Data entry standards unclear.

3. Reports difficult to access or interpret.

4. Historical information unavailable.

5. Quality control mechanisms absent.

6.6. Culture Defects.

Examples include:

1. Accountability mechanisms weak or inconsistent.

2. Recognition systems misaligned with desired behaviors.

3. Communication patterns ineffective.

4. Problem-solving approaches reactive rather than systematic.

5. Learning from failures not embedded in practice.

7.0 Plan on a Page: The Clarity Catalyst.

A one-page action plan provides essential context for each chunk, enabling effective delegation and monitoring.

7.1. Format Components.

The plan should include:

1. Issue Summary: Clear description of the problem and its impact.

2. Owner: Individual or team responsible for resolution.

3. Timeline: Start date, milestones, completion target.

4. Resources: Budget, tools, people, information required.

5. Risks: Potential obstacles and mitigation strategies.

6. Success Criteria: Measurable indicators of resolution.

7.2. Clarity Over Detail.

The plan provides sufficient information for the owner to understand the problem and approach without prescribing every step. It defines boundaries and constraints while allowing flexibility in execution.

7.3. Visual Design.

Use formatting that makes information scannable. Headers, bullet points and white space improve usability. The document should be readable in minutes, not hours.

7.4. Living Document Status.

The plan evolves as work progresses. Updates reflect changing circumstances, new information, or adjusted priorities. Regular review ensures the plan remains useful rather than becoming outdated.

8.0 SWOT Analysis: Empowering the Delegate.

Applying SWOT analysis to each chunk provides the assigned owner with strategic context for their work.

8.1. Completing SWOT for Your Team.

Leaders should not delegate SWOT creation to team members unfamiliar with organizational context.

Instead, conduct the analysis yourself or with senior staff, then provide it to the person who will execute the work. This gives them perspective they might otherwise lack.

8.2. Strengths.

Identify existing capabilities, resources, or conditions that support resolution:

1. Available budget or equipment.

2. Staff with relevant skills or experience.

3. Executive sponsorship or stakeholder support.

4. Existing documentation or procedures that can be adapted.

5. Successful similar projects that can serve as templates.

8.3. Weaknesses.

Identify internal limitations or deficiencies that must be addressed:

1. Skill gaps requiring training or external support.

2. Insufficient resources or capacity.

3. Organizational resistance or competing priorities.

4. Technical constraints or system limitations.

5. Poor communication or coordination mechanisms.

8.4. Opportunities.

Identify external factors or timing advantages that can be leveraged:

1. Upcoming projects that create urgency or visibility.

2. Regulatory changes that mandate improvement.

3. Technology advancements that enable new approaches.

4. Industry best practices that can be adopted.

5. Partnerships or vendor support available.

8.5. Threats.

Identify external factors that could derail progress:

1. Changing priorities or budget cuts.

2. Staff turnover or reorganization.

3. Competing initiatives that consume resources.

4. Vendor dependencies or supply chain issues.

5. Stakeholder opposition or political dynamics.

9.0 Delegation As Design.

Effective delegation involves assigning tasks with full context and support rather than simply transferring burden.

9.1. Context-Rich Assignment.

Provide the chunk owner with:

1. The plan on a page.

2. Completed SWOT analysis.

3. Relevant background documentation.

4. Contact information for stakeholders and subject matter experts.

5. Authorization to access required resources.

9.2. Authority With Responsibility.

Ensure the delegate has decision-making authority commensurate with their assignment. If they must seek approval for routine decisions, they cannot function effectively. Define which decisions require escalation and which they can make independently.

9.3. Support Without Micromanagement.

Establish regular check-ins that provide support without removing ownership.

Focus on removing obstacles, providing resources and ensuring alignment rather than directing every decision.

9.4. Failure as Learning.

Create conditions where team members can acknowledge challenges and adjust approaches without fear of blame.

Some chunks will require iteration. Treating setbacks as learning opportunities rather than failures builds capability.

9.5. Architectural Leadership.

The leader’s role shifts from executing work to designing systems, removing barriers, coordinating across chunks and ensuring overall coherence.

This is architectural leadership, creating conditions for others to succeed rather than succeeding through personal heroics.

10.0 Using CMMS for Systemic Issues.

CMMS platforms can track systemic improvement work beyond traditional maintenance activities.

10.1. Creating Non-Maintenance Request Types.

Configure work request or notification types specifically for systemic issues:

1. Governance gaps requiring policy development.

2. Training needs requiring curriculum development or delivery.

3. Documentation projects requiring procedure creation or revision.

4. Data cleanup requiring validation and correction.

5. Process standardization requiring workflow redesign.

10.2. Benefits of CMMS Tracking.

Using existing CMMS infrastructure provides:

1. Visibility into systemic improvement progress alongside operational work.

2. Consistent workflow for all organizational work, not just maintenance.

3. Historical record of what was addressed, when and by whom.

4. Reporting capability to demonstrate improvement over time.

5. Integration with existing approval and notification processes.

10.3. Overcoming Resistance.

Staff may initially resist using CMMS for non-maintenance work, perceiving it as scope creep. Address this by:

1. Explaining how systemic improvements support their core work.

2. Demonstrating that the system provides visibility and accountability, not additional bureaucracy.

3. Ensuring the process adds value rather than creating administrative burden.

10.4. Configuration Considerations.

Set up request types with appropriate workflows, approval chains and notification triggers. Avoid forcing systemic work into maintenance templates that do not fit. Configure fields, forms and reports specifically for the type of work being tracked.

11.0 Structuring Work Orders for System Health.

Work orders for systemic improvements should contain sufficient context and documentation to support effective execution and future reference.

11.1. Essential Attachments.

Include:

1. Plan on a page document.

2. SWOT analysis.

3. Relevant standards, policies, or regulatory references.

4. Background documentation or previous attempt reports.

5. Contact lists for stakeholders and subject matter experts.

11.2. Using CMMS Fields Creatively.

Standard maintenance fields can be repurposed:

1. Equipment/Asset: The system or process being improved.

2. Location: The department or function affected.

3. Priority: Based on impact and urgency of the systemic issue.

4. Trade/Craft: The skill set required (process design, training development, data analysis).

5. Estimated Hours: Realistic time allocation for the work.

11.3. Progress Tracking.

Use status updates and notes to document:

1. Milestones achieved.

2. Obstacles encountered and how they were addressed.

3. Decisions made and rationale.

4. Resources consumed.

5. Stakeholder feedback.

11.4. Completion Documentation.

When closing work orders, include:

1. Summary of what was accomplished.

2. Changes made to systems, processes, or documentation.

3. Training delivered or knowledge transferred.

4. Recommendations for follow-up or further improvement.

5. Lessons learned for similar future work.

12.0 Monitoring Without Micromanaging.

Effective monitoring focuses on system performance and progress indicators rather than controlling every decision.

12.1. Dashboard Design.

Create dashboards that show:

1. Work orders by status (planned, in progress, completed, overdue).

2. Progress toward milestones and completion targets.

3. Resource consumption versus budget.

4. Interdependencies between chunks and potential bottlenecks.

5. Escalations requiring leadership intervention.

12.2. Status Updates.

Establish regular reporting intervals appropriate to work duration:

1. Weekly for short-duration chunks.

2. Bi-weekly or monthly for longer projects.

3. Immediate escalation for significant obstacles or changes.

12.3. Escalation Paths.

Define clear criteria for when issues require leadership attention:

1. Work blocked by factors outside delegate’s control.

2. Resource needs exceeding allocated budget or capacity.

3. Scope changes affecting other chunks or organizational priorities.

4. Risk materialization requiring strategic decisions.

12.4. Hands-Off Observation.

Resist the temptation to intervene unless escalation criteria are met. Allow delegates to manage their chunks, solving problems and making decisions within their authority. Intervention signals lack of trust and undermines delegation effectiveness.

12.5. System-Managed Accountability.

Let the CMMS and reporting systems create accountability through transparency rather than through personal oversight.

When everyone can see progress and status, informal peer accountability often proves more effective than hierarchical monitoring.

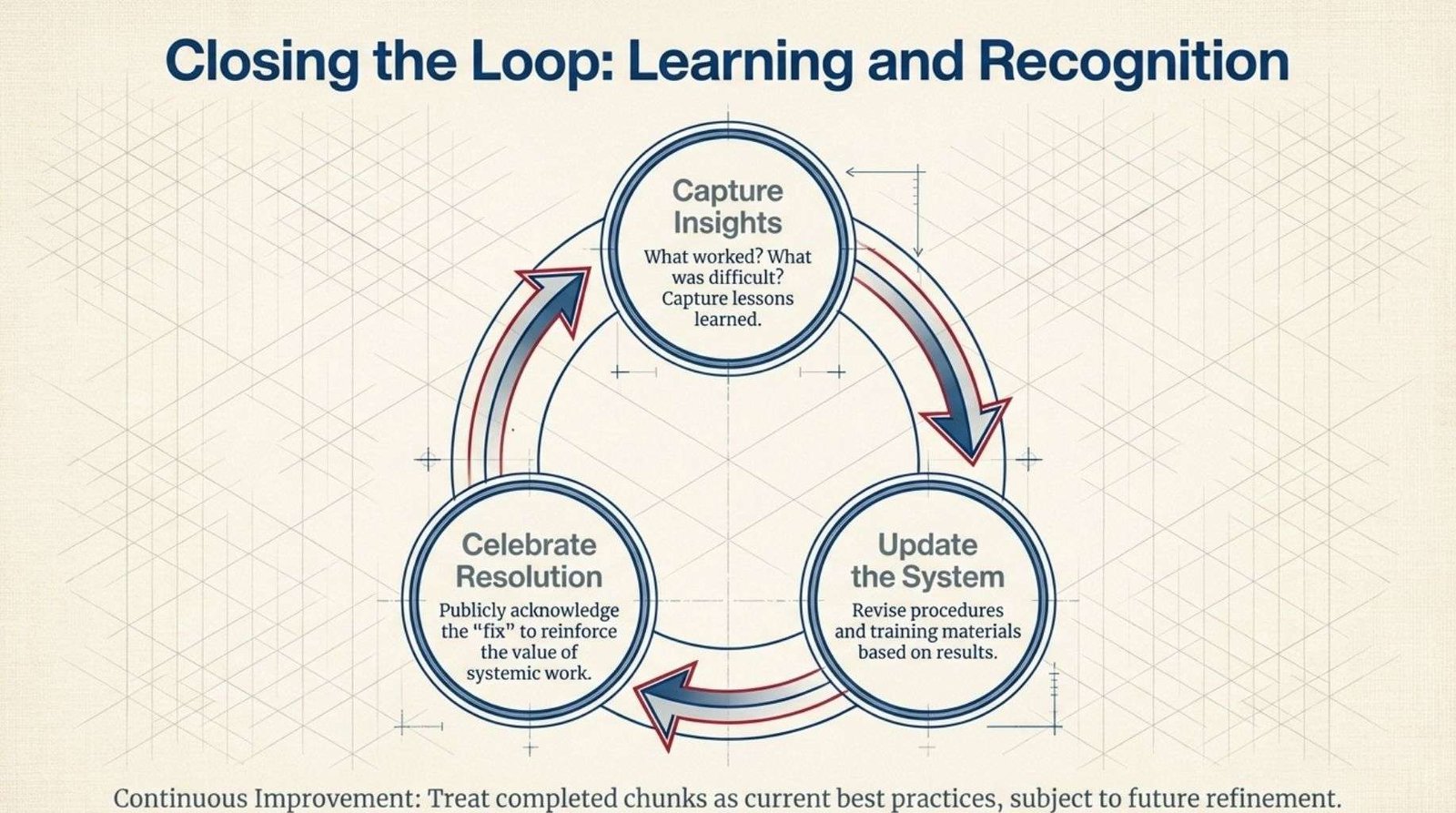

13.0 Closing the Loop: Recognition and Learning.

Completing systemic improvements requires formal recognition and knowledge capture to reinforce desired behaviors and build organizational capability.

13.1. Celebrate Resolution.

Acknowledge completion publicly:

1. Recognize individuals and teams who delivered results.

2. Communicate improvements to affected stakeholders.

3. Demonstrate leadership commitment to systemic health.

13.2. Lessons Learned Capture.

Document insights that can inform future improvement work:

1. What worked well and should be repeated.

2. What proved difficult and how obstacles were overcome.

3. What would be done differently with current knowledge.

4. Skills or resources that proved essential.

13.3. Feeding Learning Back Into Systems.

Update organizational knowledge:

1. Revise procedures based on implementation experience.

2. Update training materials to reflect new processes.

3. Modify templates or tools based on user feedback.

4. Share lessons across teams working on similar chunks.

13.4. Continuous Improvement Mindset.

Treat completed chunks not as permanent solutions but as current best practice subject to ongoing refinement.

Encourage feedback from users. Monitor performance to identify where further improvement may be needed.

13.5. Building Improvement Capability.

Each completed chunk builds organizational capability for systemic improvement. Staff gain experience in structured problem-solving.

Leaders develop skills in delegation and architectural design. The organization becomes better at identifying and addressing systemic weaknesses before they require heroic intervention.

14.0 From Hero to Architect.

Leadership transitions from bearing organizational burden to designing systems that distribute load appropriately and function reliably.

14.1. Reframing Leadership Identity.

Heroic leadership feels rewarding in the moment but proves unsustainable and ultimately harmful. Architectural leadership creates lasting value by building systems that outlive any individual’s tenure.

14.2. Designing for Resilience.

Resilient systems function effectively even when specific individuals are unavailable. They distribute knowledge, embed capability in processes and create redundancy that prevents single points of failure.

14.3. Building Capacity, Not Dependence.

Organizations grow stronger when staff develop capability to solve problems independently rather than depending on leadership intervention. This requires intentional investment in training, documentation, tools and delegation with support.

14.4. Strategic Versus Operational Focus.

Leaders who stop firefighting create time for strategic work: identifying systemic weaknesses, designing improvements, removing barriers, coordinating across functions and developing people. This work produces far greater value than solving individual operational problems.

14.5. Modeling the Transition.

Staff learn from leadership behavior. When leaders demonstrate systematic approaches, invest in processes and resist the temptation to personally solve every problem, they teach their organizations to value the same approaches.

15.0 Conclusion: Cure the Syndrome, Elevate the System.

Heroic Load Syndrome represents a failure of organizational design, not a demonstration of leadership strength.

Leaders who carry broken systems prevent those systems from developing the capability to function independently.

This creates fragility masked as strength, dependence masked as dedication and accumulating risk masked as successful operations.

The transition from hero to architect requires deliberate effort: decomposing complex problems into manageable chunks, naming systemic defects explicitly, creating clear plans with full context, conducting SWOT analysis to empower delegates and using existing tools like CMMS platforms to track improvement work alongside operational activities.

Effective monitoring focuses on system performance rather than individual oversight. Recognition and learning capture ensure that improvements build organizational capability rather than simply solving isolated problems.

The goal is not to eliminate leadership involvement but to redirect it from operational firefighting to strategic system design.

Stop carrying broken systems. Design systems that function reliably, distribute load appropriately and build resilience into organizational operations.

Use structured approaches, empower teams with context and authority and let systematic design replace heroic effort.

This shift from bearing burden to building capability represents the most important transition a leader can make.

16.0 Bibliography.

1. The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of the Learning Organization – Peter M. Senge (2010)

2. Leading Change – John P. Kotter (2012)

3. Systems Thinking for Business and Management – Jenny Leonard and Roger Leonard (2020)

4. Maintenance and Reliability Best Practices – Ramesh Gulati (2020)

5. Thinking in Systems: A Primer – Donella H. Meadows (2008)

6. Managing for Quality and Performance Excellence – James R. Evans and William M. Lindsay (2016)

7. Reliability-Centered Maintenance – John Moubray (1997)

8. Lean Maintenance – Ricky Smith (2004)

9. The Goal: A Process of Ongoing Improvement – Eliyahu M. Goldratt and Jeff Cox (2019)

10. Managing Maintenance Error: A Practical Guide – James Reason and Alan Hobbs (2003)

11. Organizational Culture and Leadership – Edgar H. Schein and Peter Schein (2016)

12. Work the System: The Simple Mechanics of Making More and Working Less – Sam Carpenter (2018)

13. The Effective Executive: The Definitive Guide to Getting Things Done – Peter F. Drucker (2006)

14. High Reliability Organizations: Managing the Unexpected – Karl E. Weick and Kathleen M. Sutcliffe (2007)

15. Continuous Improvement Strategies: Tools for Sustaining Lean Transformations – Chris Butchart (2018)

16. When Leaders Do Too Much: The Risks of Overfunctioning – Jennifer Garvey Berger, Harvard Business Review (2020)

17. Stop Being a Hero at Work – Elizabeth Doty, Strategy+Business (2017)

18. The Fixation with Firefighting in Organizations – Michael Mankins and Eric Garton, Harvard Business Review (2017)

19. Understanding Leader Burnout and Overload – Michael L. Matthews, Psychology Today (2023)

20. How to Build Systems That Work So You Don’t Have To – John Case, Inc. (2022)

21. Delegation Is an Art: How to Let Go Without Losing Control – Atlassian Team Playbook (2021)

22. Why Good Maintenance Systems Fail – Terry Wireman, ReliabilityWeb.com (2019)

23. CMMS: From Maintenance Tool to Business Intelligence Platform – Plant Engineering (2022)

24. The Real Reason Organisations Still Rely on Heroes – Bill Schaninger and Bryan Hancock, McKinsey & Company (2021)

25. Breaking Organizational Bottlenecks Through System Thinking – Forrester, Forbes Coaches Council (2020)

26. Creating a Culture of Accountability Without Micromanaging – Gallup Workplace (2022)

27. Building Sustainable Maintenance Programs – Society for Maintenance & Reliability Professionals (2024)

28. How Maintenance Management Systems Improve Compliance – CMMS Insight Editorial Team (2023)

29. Empowering Teams through Context, Not Control – MindTools Leadership (2022)

30. Why Continuous Improvement Fails Without Leadership Discipline – Robert Drexler, ReliabilityConnect (2022)