How Does Continuous Improvement Relate To Maintenance?

Disclaimer.

This article provides general information on continuous improvement within maintenance and asset management.

It does not constitute professional engineering advice, a site‑specific risk assessment, or guidance on regulatory compliance.

Organisations should seek qualified professional input before altering maintenance strategies, systems, or processes.

The practices described are indicative of common industry approaches and may not apply to all operational contexts, industries, or jurisdictions.

All opinions and interpretations expressed are solely those of the author and are offered in good faith.

Article Summary.

Continuous Improvement in maintenance is a structured, ongoing discipline that enables organisations to sustain asset reliability, control risk and protect long-term value.

Unlike project-based initiatives, it operates as a closed-loop system where work is planned, executed, measured, analysed, and refined based on evidence rather than assumption.

In environments where assets age, operating conditions shift, and failure modes evolve, standing still represents regression, not stability.

This article examines the principles, mechanisms, and organisational requirements for embedding Continuous Improvement as the operating system of maintenance and asset management.

It addresses maintenance maturity, data integrity, system enablement, governance, and the cultural foundations that determine whether improvement efforts succeed or fail.

Top 5 Takeaways.

1. Continuous Improvement is not optional in maintenance; it functions as a risk mitigation mechanism that enables organisations to detect weak signals early, refine preventive strategies, and sustain reliability in an environment where static approaches lead to silent regression.

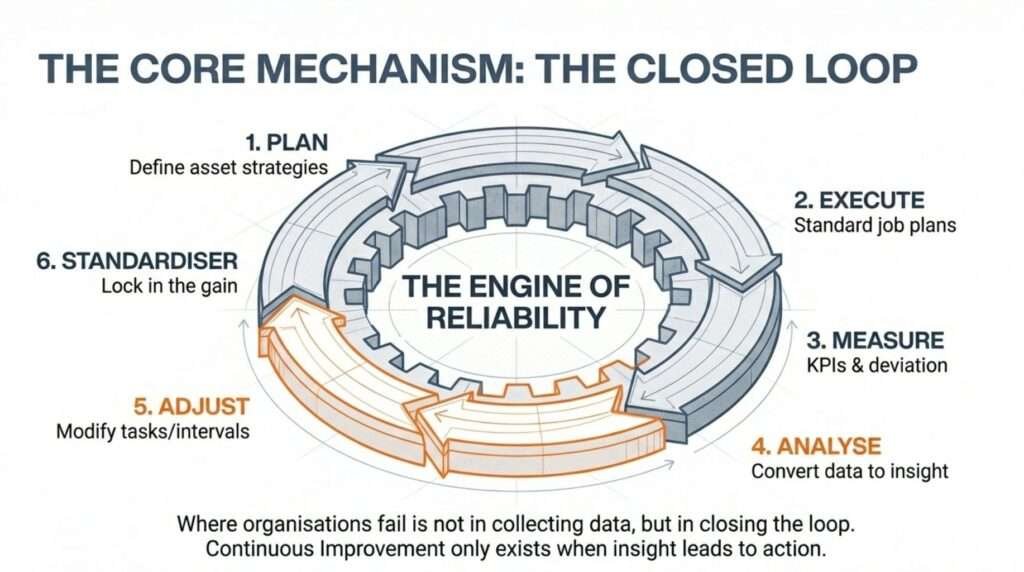

2. Effective Continuous Improvement operates as a closed-loop system (Plan, Execute, Measure, Analyse, Adjust) where insight leads to action, action leads to learning, and successful changes are standardised to ensure gains are sustained.

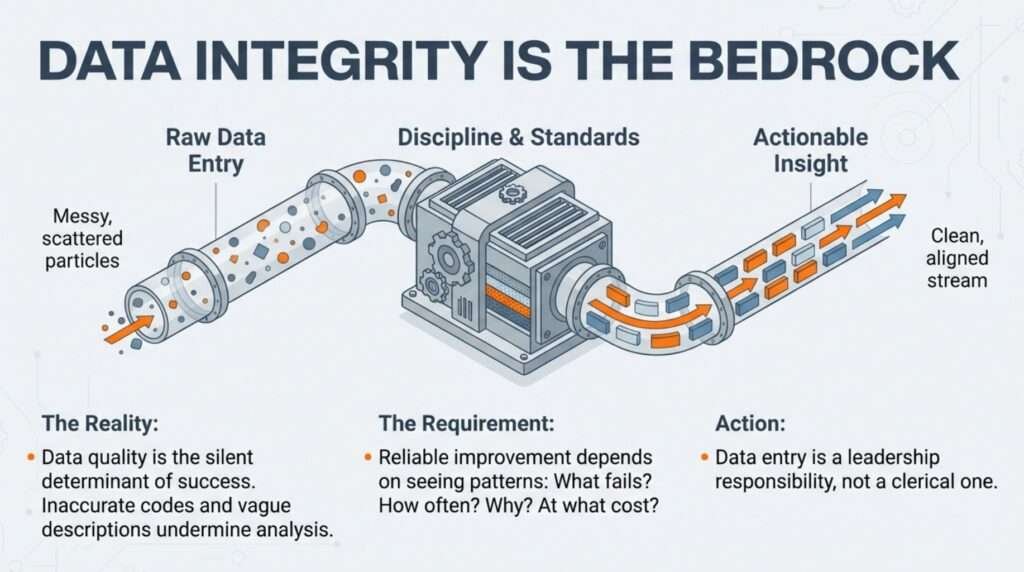

3. Data integrity is a leadership responsibility, not a clerical task; inaccurate failure codes, incomplete work orders, and inconsistent asset structures undermine analysis and lead to false conclusions that destroy strategic decision-making.

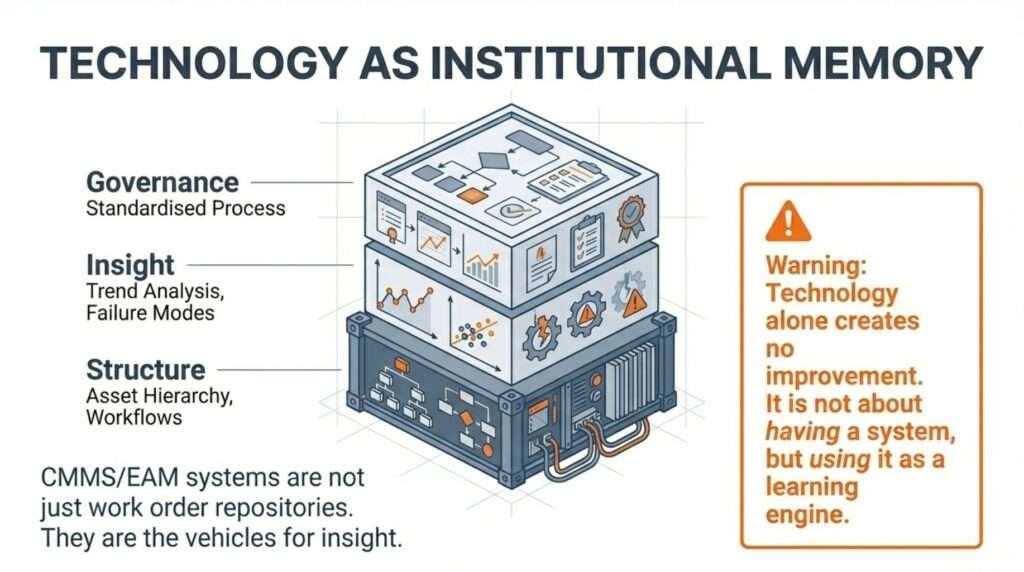

4. CMMS, EAM, and ERP systems function as institutional memory and learning engines when used intentionally; technology alone does not create improvement, disciplined use of systems to preserve knowledge and validate strategy does.

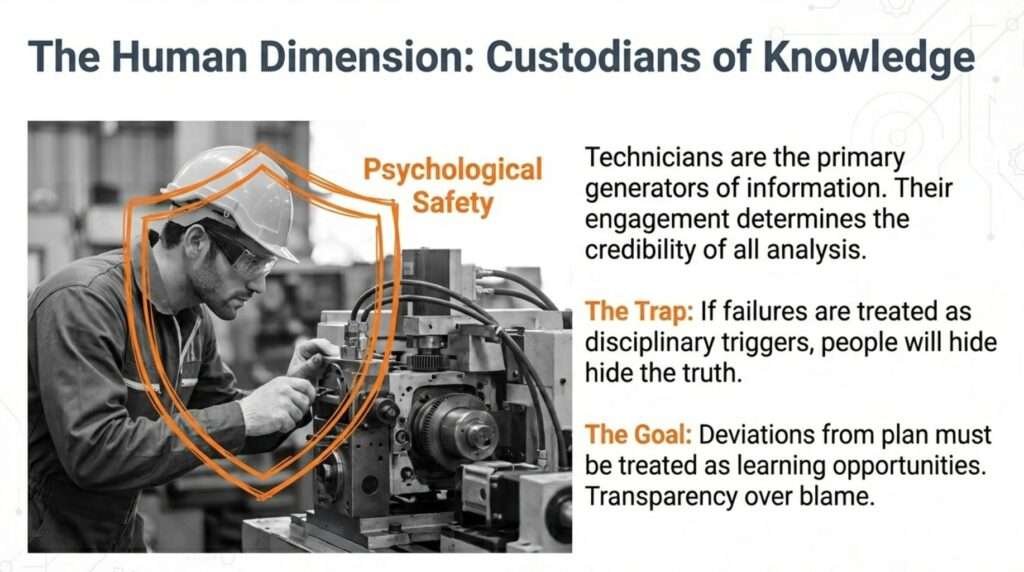

5. Psychological safety is a technical requirement for reliability; without it, technicians will not share the truth about asset condition, deviations remain hidden, and data becomes fiction, rendering improvement efforts ineffective.

Table of Contents.

1.0 Introduction.

2.0 What Continuous Improvement Means in a Maintenance Context.

3.0 Why Continuous Improvement Is Essential to Maintenance.

4.0 Maintenance Maturity and the Improvement Journey.

5.0 Continuous Improvement as a Closed-Loop System.

6.0 Culture, Behaviour, and the Human Dimension.

7.0 Maintenance Strategy as a Living System.

8.0 The Role of CMMS, EAM, and ERP Systems.

9.0 Data Integrity: The Bedrock of Improvement.

10.0 Measuring What Matters.

11.0 Governance, Standards, and Sustaining Gains.

12.0 Leadership and the Long View.

13.0 Embedding Organisational Learning and Capability

14.0 The Operating System of Maintenance.

15.0 Conclusion.

16.0 Bibliography.

1.0 Introduction.

Continuous Improvement is often presented as a universal good, something organisations pursue because it aligns with contemporary management thinking. In maintenance and asset management, the reality is more demanding.

Continuous Improvement is a non-negotiable requirement for sustaining reliability, controlling risk, and protecting long-term asset value.

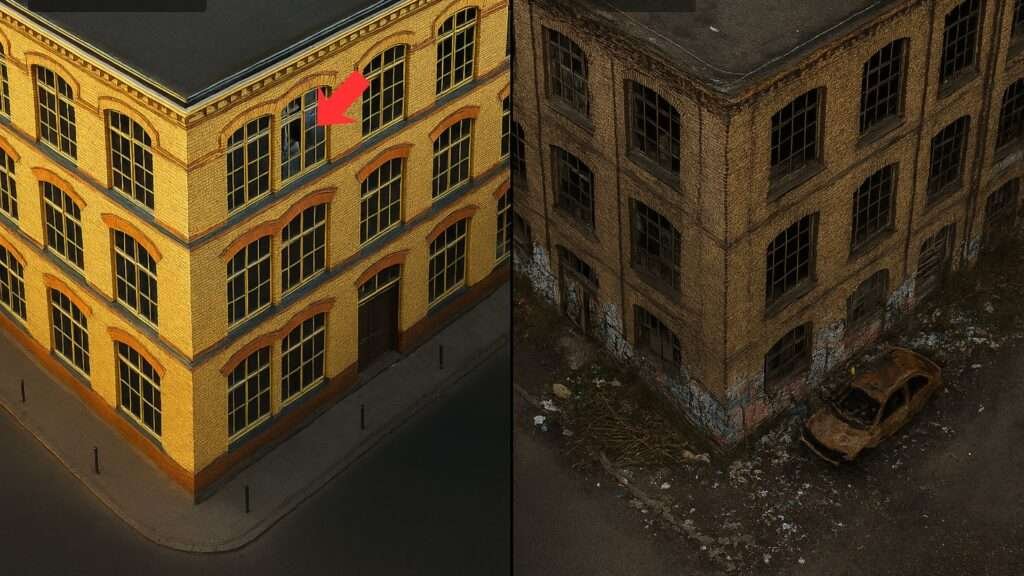

Assets do not remain static. They age, operating conditions shift, failure modes evolve, and business expectations intensify. In this environment, maintaining the status quo is not a neutral position.

It represents a form of regression where the gap between asset reality and organisational strategy widens over time.

Within maintenance departments, Continuous Improvement is the disciplined pursuit of better outcomes through learning, feedback, and refinement.

It is not a Lean toolkit, a cost-cutting initiative, or a periodic burst of enthusiasm. It is an operating philosophy that shapes how work is planned, executed, analysed, and improved.

When embedded properly, Continuous Improvement transforms maintenance from a reactive cost centre into a strategic engine of organisational performance. It provides the structure through which reliability is sustained not by chance, but by design.

2.0 What Continuous Improvement Means in a Maintenance Context.

At its core, Continuous Improvement is the structured, ongoing effort to enhance processes, systems, and outcomes through incremental learning and deliberate change.

In maintenance, this translates to continually improving asset availability, reliability, safety, cost efficiency, and lifecycle value through repeatable systems rather than heroic effort.

Unlike project-based improvement programs that have defined start and end points, Continuous Improvement has no endpoint.

It operates through closed feedback loops: plan work based on current knowledge, execute tasks to standard, measure results, analyse deviations, and adjust strategies accordingly.

Over time, this cycle builds organisational intelligence. Decisions become evidence-based rather than assumption-driven.

Improvement becomes embedded in daily operations rather than episodic interventions triggered by crisis or external pressure.

The distinction matters. Project-based improvement often creates temporary gains that erode once attention shifts elsewhere.

Continuous Improvement, when properly structured, creates sustainable capability that compounds over time.

3.0 Why Continuous Improvement Is Essential to Maintenance.

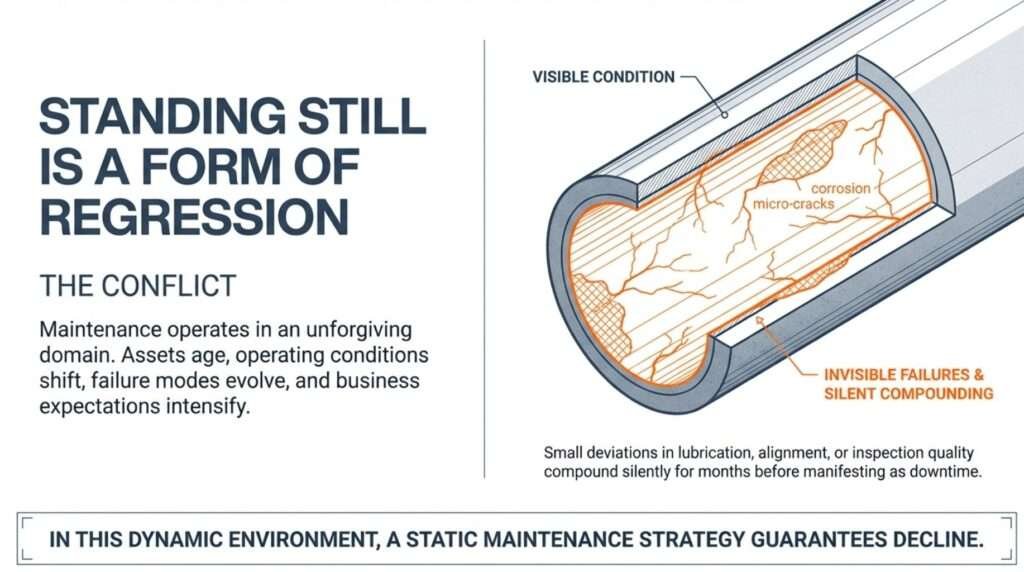

Maintenance operates in a domain where consequences can be severe and margin for error limited.

Failures can remain invisible until they become catastrophic. Small deviations in lubrication, alignment, inspection quality, or operating conditions can compound silently for months or years before manifesting as downtime, safety incidents, or premature asset replacement.

In such an environment, reactive approaches are not merely inefficient. They are dangerous. The belief that assets remain reliable simply by following original equipment manufacturer instructions is flawed.

Every machine exists in a state of continuous change. Entropy, shifting operating conditions, and small deviations accumulate over time.

Static maintenance instructions rarely reflect the reality of evolving plant conditions, particularly in operations that face extreme environments or high utilisation rates.

Continuous Improvement functions as a risk mitigation mechanism.

It enables organisations to detect weak signals early, refine preventive strategies, optimise task frequencies, eliminate non-value-adding work, and focus effort where risk and consequence are highest.

Financially, the impact is equally significant. Maintenance costs are shaped less by labour and spare parts than by the quality of upstream decisions: how assets are maintained, how failures are prevented, and how data informs strategy.

Continuous Improvement ensures these decisions evolve alongside asset behaviour rather than remaining frozen in time based on outdated assumptions.

There is no neutral position in asset management. A maintenance strategy that remains flat while the operating environment changes creates a widening performance gap.

Without evolution, organisations manage a slow-motion decline where reliability erodes incrementally until system-level failure forces reactive intervention.

4.0 Maintenance Maturity and the Improvement Journey.

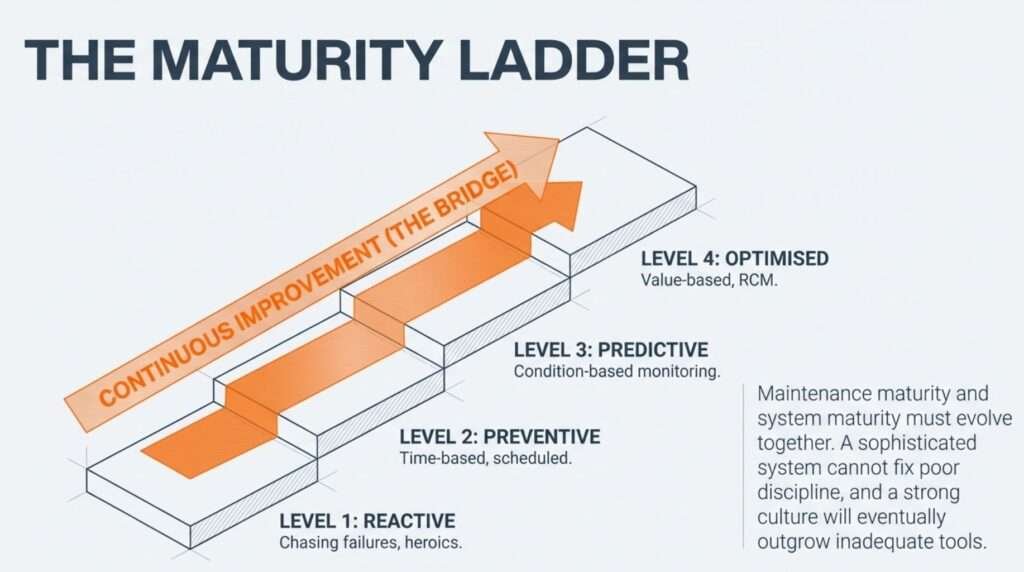

Maintenance organisations typically progress through recognisable maturity stages: reactive, preventive, predictive, reliability-centred, and ultimately optimised. Continuous Improvement exists at every stage, but its effectiveness depends on how structured and intentional it is.

At lower maturity levels, improvement is informal and personality-driven. It relies on individual experience, intuition, or isolated problem-solving efforts.

When key personnel leave, institutional knowledge disappears with them. Strategies remain static because there is no systematic mechanism to review and refine them.

As maturity increases, improvement becomes systematic. Work is planned rather than chased. Failures are analysed rather than accepted as inevitable.

Strategies are reviewed rather than assumed to be correct. The shift from assumption-driven to evidence-driven work represents the foundation of optimisation.

Crucially, maintenance maturity and system maturity must evolve together.

A sophisticated asset management system cannot compensate for poor discipline or unclear processes. Likewise, a strong improvement culture will eventually outgrow inadequate tools and systems.

Continuous Improvement acts as the bridge, aligning people, processes, and systems into a coherent whole. It provides the discipline to extract learning from operations and the structure to convert that learning into sustainable capability.

5.0 Continuous Improvement as a Closed-Loop System.

Effective Continuous Improvement in maintenance operates as a closed loop, not a linear process. The cycle consists of five core stages: Plan, Execute, Measure, Analyse, and Adjust.

It begins with clear planning: defining asset strategies, maintenance standards, and performance expectations. Work is executed using standard job plans, schedules, and procedures that reflect current best practice.

Measurement follows execution, using key performance indicators, work order data, failure information, and compliance metrics to reveal how assets and processes are performing. This stage generates the raw material for learning.

Analysis converts data into insight, identifying trends, recurring issues, and improvement opportunities.

Without this step, data remains noise. Analysis requires time, capability, and discipline to distinguish signal from variation.

Improvement actions follow: modifying tasks, updating job plans, adjusting intervals, or addressing systemic causes. These changes must be deliberate, documented, and tested to verify effectiveness.

Successful changes are then standardised and governed to ensure gains are sustained. This completes the loop and establishes a new baseline from which the next cycle begins.

Where organisations fail is not in collecting data, but in closing the loop. Continuous Improvement only exists when insight leads to action and action leads to learning. Incomplete cycles create the illusion of progress without delivering actual improvement.

6.0 Culture, Behaviour, and the Human Dimension.

Systems and processes matter, but Continuous Improvement ultimately depends on people. Technicians, planners, and supervisors are the primary generators of information and the custodians of asset knowledge.

Their engagement determines data quality, compliance, and the credibility of analysis. A culture that supports Continuous Improvement encourages transparency rather than blame.

Failures are investigated to understand causes, not assign fault. Deviations from plan are treated as learning opportunities, not disciplinary triggers.

Psychological safety is essential for surfacing the truth about asset condition and work effectiveness. Technicians hold direct knowledge of how assets behave and where processes fail.

They will not share this information in a blame-driven culture where honesty is punished. Without psychological safety, deviations are hidden, data becomes fiction, and analysis becomes meaningless.

Psychological safety is not a soft cultural preference. It is technical infrastructure. Transparency is a technical requirement for reliability.

Leadership is decisive in shaping behaviour. What leaders ask about, measure, and reward determines what the organisation prioritises.

If speed is prioritised over quality, data will suffer. If compliance is emphasised without context, improvement will stagnate.

Continuous Improvement thrives when leadership reinforces learning, discipline, and long-term thinking. It fails when short-term pressures consistently override the conditions needed for systematic learning.

7.0 Maintenance Strategy as a Living System.

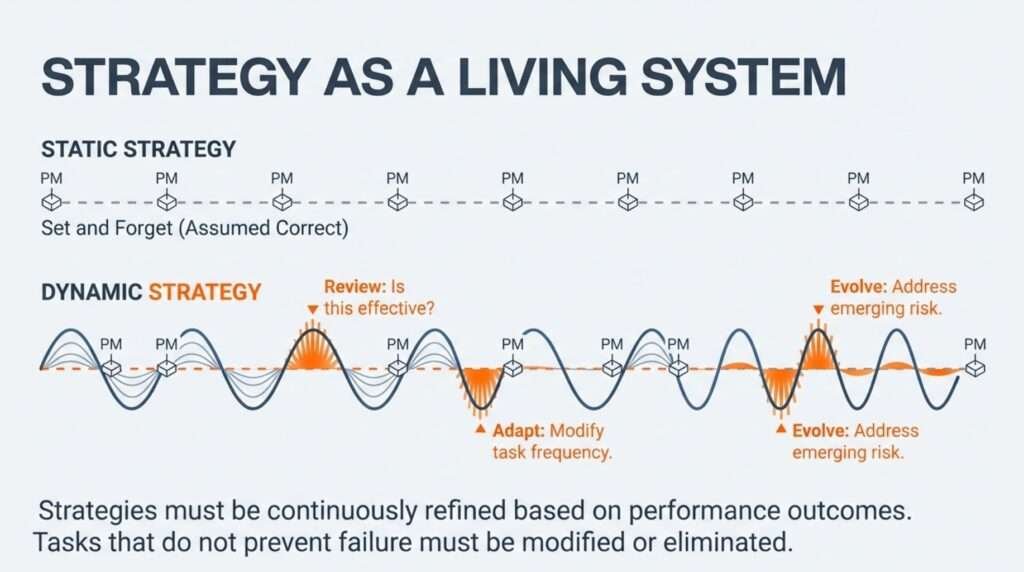

One of the most powerful applications of Continuous Improvement is in maintenance strategy itself.

Preventive maintenance programs, inspection regimes, and task frequencies should not be static artefacts created once and forgotten.

They should be living systems, continuously refined based on performance outcomes and failure behaviour.

High-maturity organisations treat maintenance strategy as a continuous cycle. Preventive maintenance programs are never “finished.”

Tasks that no longer prevent failure are modified or removed. Effort is redirected to the highest-risk areas based on evidence rather than historical assumptions.

Through structured analysis, trend reviews, root cause investigations, and cost-risk assessments, organisations can determine whether existing strategies are effective or require adjustment. Emerging risks can be addressed proactively before they manifest as failures.

This adaptive approach ensures maintenance effort remains aligned with asset reality rather than frozen assumptions documented years earlier under different operating conditions.

It converts static manuals into dynamic systems that evolve as the asset base evolves. The shift from assumption-driven to evidence-driven strategy is not theoretical. It directly impacts reliability, cost, and risk exposure.

8.0 The Role of CMMS, EAM, and ERP Systems.

CMMS, EAM, and ERP platforms are central enablers of Continuous Improvement, but only when used intentionally.

These systems are not administrative burdens or work order repositories. They are the institutional memory of the maintenance organisation.

At a foundational level, they provide structure: asset hierarchies, workflows, scheduling, and history. This establishes consistency and ensures work is planned and tracked systematically.

At higher maturity, they enable insight: trend analysis, failure mode visibility, performance tracking, and strategy validation. Data captured through daily operations becomes the foundation for learning and refinement.

Ultimately, they support governance by standardising processes and preserving learning beyond individual experience.

When technicians leave, their knowledge remains accessible through work order histories, failure records, and documented task refinements.

Technology alone does not create improvement. Poor configuration, inconsistent data entry, and weak analytical discipline can render even the most advanced system ineffective. Continuous Improvement depends not on having a system, but on using it as a learning engine.

A CMMS is not an inbox. It is organisational memory. With standardisation and analytical discipline, it becomes the mechanism through which knowledge is preserved and strategy is validated.

9.0 Data Integrity: The Bedrock of Improvement.

Data quality is the silent determinant of Continuous Improvement success. Inaccurate failure codes, incomplete work orders, inconsistent asset structures and vague descriptions undermine analysis and lead to false conclusions.

Reliable improvement depends on the ability to see patterns over time: what fails, how often, why, and at what cost.

This requires discipline at the point of data entry and clear standards for how information is captured and used.

Data integrity is not a clerical issue. It is a leadership and governance responsibility. Poor data quality destroys analysis and leads to strategic failure.

Treating data as administrative work guarantees that decisions will be based on fiction rather than fact.

When data quality is high, improvement priorities become obvious. Resources are better targeted. Debates shift from opinion to evidence.

Governance operates through leading indicators rather than lagging surprises.

High-integrity data enables the closed-loop system to function.

Without it, the cycle breaks. Insight cannot be extracted from unreliable inputs, and actions based on flawed analysis create risk rather than reducing it.

10.0 Measuring What Matters.

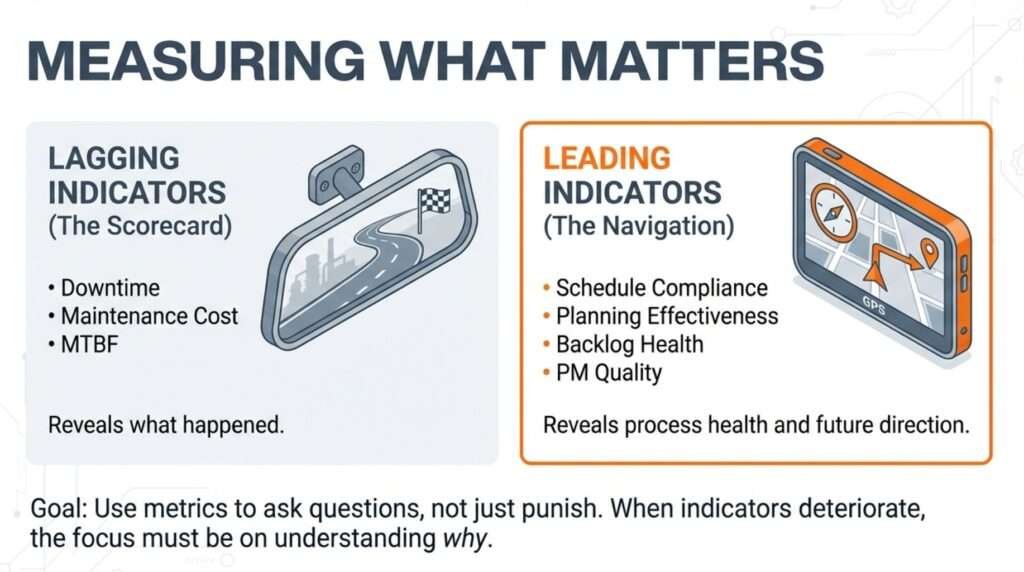

Continuous Improvement requires meaningful measurement, not excessive measurement. The goal is not to track everything, but to monitor indicators that guide learning and action.

Metrics generally fall into two categories. Lagging indicators reveal outcomes: downtime, cost, mean time between failures, and asset availability.

These measures confirm what has already occurred and provide a historical perspective on performance.

Leading indicators reveal process health: planning effectiveness, schedule compliance, backlog health, and preventive maintenance quality.

These measures provide early signals about whether processes are functioning as intended and whether performance is likely to improve or deteriorate.

Effective organisations use metrics to ask better questions. When indicators deteriorate, the focus shifts to understanding why and what can be improved. Metrics become navigational tools rather than scorecards used for blame or performance ranking.

As maturity increases, measurement systems must evolve. What matters in a reactive environment differs from what matters in an optimised one.

Early-stage organisations focus on basic compliance and execution discipline. Mature organisations focus on strategy effectiveness and value optimisation.

Measurement drives attention and the challenge is to ensure attention remains focused on what enables improvement rather than what creates the appearance of control.

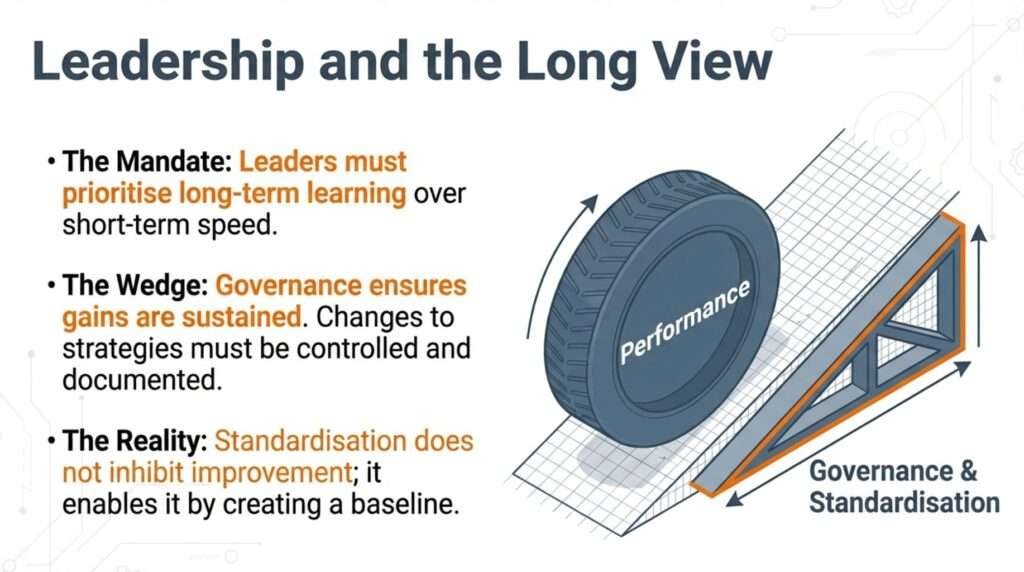

11.0 Governance, Standards, and Sustaining Gains.

Without governance, Continuous Improvement becomes fragmented and inconsistent. Changes to strategies, job plans, and system configurations must be controlled, reviewed, and documented.

This ensures improvements are deliberate, repeatable, and auditable.

Standardisation does not inhibit improvement. It enables it.

Clear baselines allow organisations to distinguish between variation and true improvement.

Without standards, every change appears novel and it becomes impossible to determine whether performance has genuinely improved or simply shifted.

CMMS and EAM systems reinforce governance through workflows, approvals, and version control.

Changes to asset strategies or maintenance tasks are logged, reviewed, and preserved. This creates accountability and ensures that learning is not lost when personnel change.

Sustained improvement depends not on constant change, but on disciplined evolution. Organisations that change everything continuously create instability and lose the ability to measure impact.

Organisations that change nothing tend to stagnate.

The balance lies in structured governance: defining clear processes for how improvements are proposed, tested, validated, and implemented.

This creates stability while enabling evolution.

12.0 Leadership and the Long View.

Continuous Improvement is ultimately a leadership choice. It requires patience, investment, and a willingness to prioritise long-term performance over short-term convenience.

Maintenance leaders must create space for analysis, support capability development, and reinforce discipline even when operational pressures mount.

This means protecting time for planning, investigation, and refinement when the default response is to chase urgent work.

When leadership commitment is genuine, Continuous Improvement becomes self-reinforcing. Teams see the impact of their efforts, trust the systems they use, and contribute actively to organisational learning.

When commitment is superficial, improvement initiatives become compliance exercises that consume time without delivering value.

Leadership also determines whether psychological safety exists. If failures are met with punishment, technicians will hide problems.

If deviations trigger blame, data will be sanitised to avoid consequences. These behaviours are rational responses to unsafe environments.

They also make improvement impossible.

The long view requires accepting that meaningful improvement takes time. Quick wins may be possible, but sustainable capability is built through repeated cycles of learning and refinement.

Leaders who demand immediate results without investing in the conditions that enable learning create the appearance of progress without the substance.

13.0 Embedding Organisational Learning and Capability.

Continuous Improvement in maintenance cannot exist without an organisational ecosystem that values learning as much as performance.

Systems and standards provide structure, but the people who operate within them determine whether improvement becomes a living discipline or fades into compliance paperwork.

Sustaining momentum requires deliberate investment in capability, clarity, and connection across all levels of the organisation.

Capability development is the first foundation. Improvement depends on analytical competence, the ability to interpret data, identify patterns, and translate root cause findings into practical change.

Technicians, planners, and engineers require continuous training not only in technical skills but in systems thinking and problem analysis.

When a maintenance workforce understands how its work connects to asset risk, cost, and reliability, it becomes an intelligent system capable of self-correction.

Without this shared understanding, improvement efforts rely on isolated experts and collapse when those individuals move on.

Feedback systems form the second foundation. Organisations that learn continuously operate on real‑time visibility.

They build mechanisms that capture frontline observations, convert them into structured data, and feed that information into planning and strategy reviews.

A failed bearing or misaligned coupling is never just a maintenance event, it is a data point in a learning process.

Effective teams hold short, structured reviews where events are discussed constructively, lessons are captured directly into CMMS fields or improvement logs, and agreed changes are documented and tracked.

These small feedback cycles keep improvement alive between major reviews.

Cross‑functional alignment is the third foundation. Maintenance improvement cannot succeed in isolation from operations, procurement, and engineering. When production targets override maintenance discipline, or when procurement decisions prioritise lowest cost over reliability, improvement loops break.

Mature organisations establish joint ownership of reliability metrics. Maintenance and operations share targets, review common dashboards and align improvement priorities.

This integration prevents the systemic friction that makes improvement unsustainable.

Leadership then acts as the catalyst that holds this ecosystem together. The role of leadership is not to drive every initiative personally, but to ensure that learning has structure, signals, and sponsorship.

This means allocating protected time for root cause analysis and review meetings, ensuring that improvement actions are visible in work management systems, and celebrating learning outcomes as visibly as performance targets.

When leaders model curiosity and humility, asking “What did we learn?” rather than “Who is to blame?” they provide cultural permission for honesty and experimentation.

Over time, these practices accumulate into organisational memory. Improvement ceases to depend on enthusiasm or crisis response and becomes an operational rhythm. The CMMS transforms into a learning repository.

The planning function evolves from scheduling tasks to orchestrating knowledge flow. Continuous Improvement, when institutionalised in this way, becomes self-sustaining, a cycle powered not by directives but by collective habit.

In this environment, reliability is not a destination but an ongoing conversation between people, data, and systems.

The organisation becomes adaptive rather than reactive, compounding its capability over time.

It is this integration of human learning with technical discipline that defines the highest maturity of maintenance performance, where Continuous Improvement is not just what the organisation does, but who it is.

14.0 The Operating System of Maintenance.

When fully embedded, Continuous Improvement becomes the operating system of maintenance and asset management.

It connects people, processes, and technology into a coherent, learning-driven system and CMMS, EAM, and ERP platforms become more than tools.

They become vehicles for insight and institutional memory. Work orders are not administrative tasks but learning opportunities. Failures are not setbacks but data points that refine strategy.

Technicians are not simply executors of predefined tasks. They are observers who contribute knowledge about asset behaviour and process effectiveness. Planners are not schedulers.

They are strategists who ensure work aligns with risk and value.

In this environment, reliability is not maintained by chance or heroic effort.

It is sustained through disciplined, continuous evolution.

Strategies adapt as assets age. Tasks are refined as failure modes emerge. Resources are allocated based on evidence rather than historical patterns or political pressure.

The contrast with reactive organisations is stark. Reactive organisations treat maintenance as a necessary cost to be minimised. Optimised organisations treat it as a strategic capability that protects value and enables performance.

15.0 Conclusion.

Assets age, risk evolves,

and expectations rise and that’s just the way it goes.

Continuous Improvement is

not optional and it is how maintenance organisations remain reliable in a

sometimes unreliable world.

It is how asset performance

is sustained not by chance, but by design.

The illusion that assets

remain reliable simply by following static instructions is dangerous. Every

machine exists in a state of continuous change.

Entropy, operating conditions,

and small deviations accumulate silently. Without disciplined evolution,

organisations manage a slow-motion decline.

Continuous Improvement provides the structure to detect weak signals early, refine strategies based on evidence, and ensure that maintenance effort remains aligned with asset reality.

It requires leadership commitment, cultural safety, data integrity, and system discipline. When these elements align, maintenance transforms from a reactive function into a strategic engine of organisational performance.

16.0 Bibliography.

1. Maintenance and Reliability Best Practices, 3rd Edition – Ramesh Gulati

2. Reliability-Centered Maintenance II – John Moubray

3. Lean Maintenance – Ricky Smith & Bruce Hawkins

4. Maintenance Planning and Scheduling Handbook – Doc Palmer

6. Reliability Engineering and Asset Management – Michael D. Holloway

7. Total Productive Maintenance: Proven Strategies and Techniques – Terry Wireman

8. The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of The Learning Organization – Peter Senge

9. Learning from Accidents – Trevor Kletz

10. Handbook of Maintenance Management and Engineering – Mohamed Ben-Daya et al.

11. Reliability-Centered Maintenance: Implementation Made Simple – Neil Bloom

12. Practical Machinery Management for Process Plants, Volume 1 – Heinz Bloch & Fred Geitner

13. Foundations of Maintenance Management – Terry Wireman

14. Root Cause Analysis Handbook – ABS Consulting

15. Reliability, Maintainability, and Risk – David J. Smith

16. ISO 55000: Asset Management Overview – ISO

17. Continuous Improvement in Maintenance – Reliable Plant Magazine

18. How to Build a Continuous Improvement Culture in Maintenance – Fiix Software

19. Data Integrity in Maintenance Systems – Plant Engineering

20. The Role of CMMS in Continuous Improvement – Fluke Reliability

21. Leadership and Maintenance Culture – Uptime Magazine

22. Embedding Reliability Improvement – Assetivity

23. Maintenance Strategy Optimization – ARMS Reliability

24. Psychological Safety and Operational Reliability – SafetyCulture

25. Understanding Maintenance Maturity Models – IDC Technologies

26. Operational Excellence Through Continuous Improvement – Allied Reliability

27. Root Cause Analysis for Maintenance – UpKeep Maintenance Blog

28. Governance in Asset Management – IAM (Institute of Asset Management)

29. Creating an Improvement Ecosystem in Maintenance – Reliable Plant

30. Organisational Learning and Reliability – Harvard Business Review