Regulatory Guidelines & Asset Management Systems in Mining

Disclaimer.

This article provides general information about government guidelines and asset management software in mining operations. It is not legal advice, regulatory guidance, or a substitute for professional consultation.

Mining regulations vary significantly by jurisdiction and operators must consult with qualified legal, engineering and safety professionals and comply with applicable local, regional and national laws.

The examples provided are illustrative and do not represent specific companies, incidents, or endorsements.

Software capabilities vary by vendor and implementation.

Readers should conduct their own due diligence before making decisions regarding compliance strategies or technology investments.

Thoughts, views, opinions and ideas expressed are those of the Author only.

Article Summary.

Mining remains one of the world’s most heavily regulated and high-risk industries globally, where equipment failures, environmental incidents, or safety lapses can result in catastrophic consequences.

Government guidelines and codes of practice exist worldwide to translate complex mining legislation into practical, accessible frameworks that protect workers, communities and the environment.

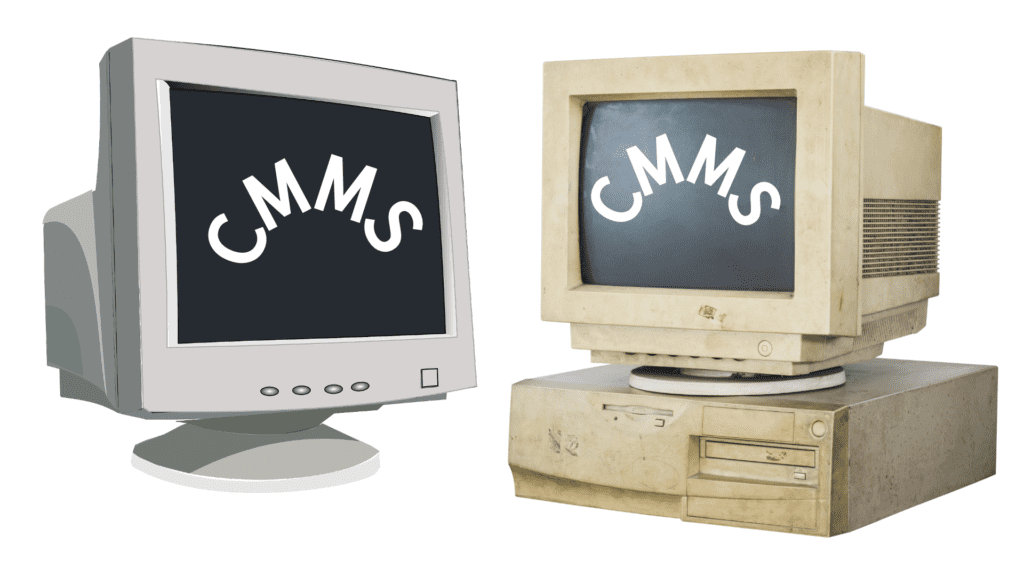

Asset management software has evolved from simple paper-based systems and spreadsheets into sophisticated CMMS, EAM and ERP platforms capable of operationalising regulatory requirements, enforcing compliance workflows and generating audit-ready documentation.

The emergence of artificial intelligence is now accelerating this evolution, introducing predictive capabilities, automated compliance monitoring and data-driven insights that were previously impossible.

This article examines why government guidelines are essential in mining, how quality asset management software supports compliance to these guidelines.

It also looks at why the integration of guidelines, systems and emerging technologies represent a strategic advantage for mining operators in an increasingly complex regulatory environment.

Top 5 Takeaways.

1. Government guidelines bridge the gap between complex mining legislation and practical implementation, providing accessible, mining-specific guidance that helps operators understand and meet their legal obligations across diverse equipment types and operating environments.

2. Quality asset management software transforms regulatory compliance from a paper-based burden into a systematic, auditable process, enabling real-time tracking of statutory inspections, certifications, critical controls and maintenance activities across entire mining operations.

3. High-risk mining environments benefit most from the integration of guidelines and quality systems, where the consequences of equipment failure extend beyond production losses to include catastrophic safety incidents, environmental disasters and severe legal exposure.

4. Modern CMMS, EAM and ERP platforms have evolved beyond simple maintenance tracking to become enterprise-wide ecosystems that integrate safety, engineering, materials management, contractor oversight and competency verification into unified workflows.

5. Artificial intelligence is fundamentally changing asset management in mining, introducing predictive maintenance, automated compliance monitoring and continuous improvement capabilities that make predicting the future of these systems increasingly difficult, underscoring the importance of focusing on quality, data integrity and governance today.

Table of Contents.

1.0 Introduction.

2.0 The Role of Government Guidelines in Mining.

3.0 Quality Asset Management Software.

4.0 How Software Ensures Compliance.

5.0 High-Risk Environments and Quality Systems.

6.0 The AI Acceleration.

7.0 Conclusion.

8.0 Bibliography.

1.0 Introduction.

The processes involved in mining, from extracting ore to transforming raw materials into finished products, place the industry among the world’s most tightly regulated and inherently high‑risk sectors.

Given the persistent hazard profile and the trend toward increasingly stringent oversight, this reality is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future.

Mining operations involve massive mobile equipment weighing hundreds of tonnes, underground environments where geotechnical instability can trigger catastrophic failures, electrical systems operating at lethal voltages, pressure vessels containing explosive gases and hazardous materials that pose acute environmental and health risks.

Government guidelines, standards and codes of practice exist precisely because mining legislation alone cannot capture the technical complexity and operational diversity of modern mining.

Statutes establish legal requirements and penalties, but they rarely provide the granular detail needed for maintenance supervisors to verify a haul truck’s braking system meets safety standards, or for engineers to determine appropriate inspection intervals for equipment operating in corrosive environments. Guidelines fill this gap by translating legal obligations into practical, actionable frameworks.

Asset management software has undergone remarkable evolution.

What began as paper-based maintenance logs and spreadsheets has transformed into comprehensive CMMS platforms. From there it expanded into EAM systems integrating reliability engineering and further evolved into enterprise-wide ERP ecosystems connecting maintenance, procurement, finance, human resources and safety into unified platforms.

Artificial intelligence is now accelerating this evolution at unprecedented rates.

Machine learning algorithms analyse vibration patterns to predict bearing failures weeks in advance.

Natural language processing extracts critical information from decades of maintenance notes.

Computer vision systems inspect equipment faster and more consistently than human observers. AI models identify compliance gaps by cross-referencing equipment histories against regulatory requirements automatically.

The convergence of comprehensive government guidelines, quality asset management systems and emerging AI technologies represents more than operational efficiency.

It constitutes a strategic advantage in an industry where regulatory scrutiny intensifies annually, where equipment failures can result in fatalities and where excellence in asset management directly correlates with safety performance, operational reliability and long-term viability.

2.0 The Role of Government Guidelines in Mining.

2.1 Why Mining Needs Clear Guidelines.

Mining operations involve hazards that are both diverse and severe, creating unique regulatory challenges that simple legislation cannot adequately address.

Heavy mobile equipment represents one of the most visible risks.

Haul trucks exceeding 450 tonnes, wheel loaders with massive bucket capacities around 40.5 cu m as with the Komatsu WE-2350 and excavators such as the Caterpillar 6090 FS with a bucket capacity of 50 cu m and an operating weight of around 1,000 tonnes.

Guidelines address specific technical requirements for these machines, including brake testing protocols, rollover protective structure standards, visibility requirements and pre-operational inspection criteria.

Underground environments introduce hazards absent from surface operations.

Ground instability can cause rock falls or catastrophic collapses.

Ventilation failures can create oxygen-deficient or toxic atmospheres within minutes. Fire and explosion risks escalate in enclosed areas where escape routes are limited.

Guidelines for underground mining address ground support systems, ventilation design and monitoring, emergency refuge chambers and electrical equipment suitable for potentially explosive atmospheres.

Electrical systems in mining operate at voltages ranging from low-voltage mobile equipment to high-voltage substations exceeding 100 kilovolts.

Arc flash incidents, electrocution and electrical fires pose immediate threats to life. Guidelines establish standards for electrical design, installation, isolation procedures, testing regimes and competency requirements for electrical workers.

Pressure systems including compressed air networks, hydraulic systems and autoclaves operate throughout mining operations.

Catastrophic failures can release stored energy instantly, resulting in explosions and projectile hazards. Guidelines specify design codes, inspection frequencies, pressure testing requirements and competent person qualifications.

Remote operations present unique challenges that compound other hazards. Distance from population centres means emergency medical services may require hours to reach incident sites.

Extreme weather can isolate mine sites for extended periods. Guidelines for remote operations address emergency response planning, medical capabilities, communication systems and fatigue management programs.

2.2 What Guidelines Typically Cover.

Government guidelines and codes of practice address common categories of technical and operational requirements across mining jurisdictions worldwide.

Mobile equipment safety guidelines establish requirements for design, operation, maintenance and inspection.

They address structural integrity, braking system performance and testing, steering system reliability, operator visibility, warning systems, operator competency and licensing, pre-operational inspection procedures and traffic management systems.

Fixed plant maintenance guidelines cover stationary equipment including crushers, mills, conveyors and processing equipment.

They establish requirements for equipment guarding, isolation and lockout procedures, confined space entry protocols, working at heights, statutory inspection intervals, competent person requirements and documentation of maintenance activities.

Electrical safety guidelines address both fixed infrastructure and mobile equipment electrical systems.

Coverage includes electrical design standards, isolation and testing procedures, personal protective equipment, arc flash risk assessment, competency requirements, inspection and testing frequencies and emergency response to electrical incidents.

Lifting and rigging guidelines establish requirements for cranes, hoists, slings and rigging hardware.

They address equipment certification and inspection, statutory inspection intervals, competent person qualifications, load rating and identification, operator competency, pre-use inspections and defect criteria.

Isolation and lockout guidelines protect workers from hazardous energy during maintenance activities.

They establish requirements for isolation procedures covering electrical, mechanical, hydraulic, pneumatic and stored energy sources, lockout device specifications, group lockout procedures, verification testing and permit to work integration.

Emergency response guidelines address preparation for and response to mining emergencies including fires, explosions, inundations and toxic gas releases.

They cover emergency response plan development, emergency equipment provision, personnel training requirements, communication systems, evacuation procedures and rescue capabilities.

Competency and training guidelines establish requirements for personnel performing safety-critical roles.

They address qualification pathways, training program content, assessment methods, currency requirements including refresher training and record-keeping.

Statutory inspections establish requirements for periodic examination of equipment by competent persons.

They specify inspection frequencies based on equipment type and risk classification, competent person qualification requirements, inspection scope and methods, defect classification and documentation standards.

2.3 How Guidelines Bridge the Gap Between Law and Practice.

Mining legislation establishes legal obligations and penalties but rarely provides sufficient detail for practical implementation.

A statute might require that mobile equipment be maintained in safe working order, but it typically does not specify brake testing frequencies, acceptable deceleration rates, or documentation requirements.

Guidelines bridge this gap by translating general legal requirements into specific, measurable and actionable standards.

They answer practical questions: how often must this equipment be inspected, what qualifications must the inspector hold, what tests must be performed, what constitutes a defect requiring immediate action and what records must be maintained?

Accessibility represents another critical function. Mining legislation often employs legal terminology and references other statutes in ways that require legal expertise to interpret.

Guidelines use more direct language focused on technical requirements and operational procedures. They often include diagrams, photographs and worked examples that illustrate requirements in familiar mining contexts.

Guidelines also provide practical interpretation of how general legal principles apply to specific mining equipment and situations.

Guidelines developed through consultation with regulators, industry associations, technical experts and operators gain broader acceptance and compliance than those imposed without industry input.

2.4 The Global Nature of Mining Regulation.

Mining regulation shows notable similarities across major jurisdictions, even though their legal systems and regulatory structures differ significantly.

Australia operates under a federated system where individual states and territories regulate mining through separate legislation and guidelines.

Australian mining guidelines share common principles including risk-based regulation, performance-based standards, statutory inspection regimes and competency-based training systems.

Canada operates under provincial jurisdiction for mining safety.

Canadian mining regulation emphasises joint health and safety committees, worker participation in safety management, certification of equipment and systems and competent person requirements for statutory inspections.

South Africa operates under national mining legislation.

South African mining regulation reflects the country’s deep-level underground mining experience, with comprehensive requirements for ground control, rock burst management and emergency response.

Chile regulates mining through the National Service of Geology and Mining. Chilean mining guidelines reflect the prominence of large-scale open pit copper mining and high-altitude operations, addressing slope stability at scale, oxygen-deficient atmospheres and extreme weather conditions.

United States operates under both federal and state regulation through the Mine Safety and Health Administration and state mining authorities. American mining regulations include detailed prescriptive requirements alongside performance-based standards.

European Union influences mining regulation across member states through directives addressing workplace safety, machinery safety and environmental protection, though mining-specific regulation remains primarily national.

Common themes emerge across these diverse jurisdictions.

Most major mining nations require periodic statutory inspections of critical equipment by competent persons.

They establish competency requirements for personnel performing safety-critical roles. Most require documented risk assessments before commencing new activities and require investigation and reporting of serious incidents.

2.5 Why Guidelines Are Essential for Risk Mitigation.

Guidelines contribute directly to risk mitigation across multiple dimensions of mining operations.

Preventing catastrophic failures requires systematic approaches to equipment maintenance, inspection and verification. Guidelines establish the inspection intervals, testing methods, defect criteria and competent person requirements that detect deterioration before it reaches critical levels.

Ensuring equipment integrity throughout operational life depends on maintenance programs aligned with equipment design, operating conditions and failure modes. Guidelines inform maintenance planning by specifying minimum requirements for critical equipment and systems.

Protecting workers from hazards requires controls implemented consistently across shifts, crews and contractors.

Guidelines establish non-negotiable minimum controls that must be in place before work proceeds, including isolation requirements, confined space entry procedures and working at heights controls.

Reducing environmental harm depends on preventing equipment failures that can release hazardous substances and maintaining containment systems. Guidelines establish requirements for monitoring systems, inspection programs and emergency response capabilities that reduce both incident likelihood and consequence severity.

Avoiding legal consequences requires demonstrating that operations have implemented reasonably practicable measures to manage mining risks.

Operations that have systematically implemented guideline requirements can demonstrate due diligence. Those that have ignored guidelines face prosecution, penalties and potential closure.

Financial consequences of incidents extend beyond regulatory penalties to include production losses, equipment replacement costs, increased insurance premiums, reduced access to capital and litigation costs. Major mining incidents can result in costs measured in hundreds of millions of dollars.

3.0 Quality Asset Management Software.

3.1 Evolution of Maintenance Software in Mining.

Asset management software in mining has evolved through distinct phases, each expanding capability and integration.

Paper-based systems dominated mining maintenance management for decades. Maintenance records existed as handwritten logs.

Planning occurred using wall charts. This approach provided basic documentation but offered limited analysis capability, no integration between functions, high administrative burden and poor accessibility of historical information.

Spreadsheets became one of the earliest widely adopted tools for computerising maintenance data, enabling planners to build equipment registers, track work orders, and manage parts inventory long before modern CMMS platforms were available.

However, they remained isolated from other business systems, offered limited multi-user capability, provided no workflow automation and scaled poorly.

CMMS platforms emerged as purpose-built maintenance management systems.

Early CMMS implemented work order management, preventive maintenance scheduling based on time or meter intervals, parts inventory management and basic reporting on maintenance costs and equipment downtime.

EAM systems expanded beyond maintenance management to encompass broader asset lifecycle management.

EAM platforms integrated reliability engineering including failure mode analysis and reliability centred maintenance methodologies.

They added project management capabilities, asset performance management, lifecycle costing and condition monitoring integration.

ERP ecosystems extended integration to entire enterprises, connecting maintenance with procurement, finance, human resources, production planning and inventory management.

Modern ERP platforms treat maintenance as an integrated business process rather than isolated function.

AI-enabled platforms are now introducing capabilities that were impossible in previous generations. Machine learning analyses historical failure data to predict equipment degradation.

Natural language processing extracts insights from unstructured maintenance notes. Computer vision automates equipment inspections. Anomaly detection identifies unusual equipment behaviour indicating developing failures.

This evolution reflects both technological advancement and changing expectations. Early systems focused on recording what occurred.

Modern systems enforce what must occur, predict what will occur and optimise how it occurs.

3.2 What “Quality” Means in Asset Management Software.

Quality in asset management software extends beyond basic functionality to encompass characteristics that determine whether systems support or hinder mining operations.

Data integrity represents the foundation. Quality systems enforce data integrity through mandatory fields. This prevents incomplete records, validation rules rejecting invalid entries, audit trails tracking all data changes, referential integrity preventing broken relationships and backup capabilities protecting against data loss.

Standardised workflows ensure maintenance activities occur consistently.

Quality systems provide work order templates for common tasks, checklist functionality ensuring required steps are completed, approval routing for high-risk work, permit to work integration and sequenced task lists guiding technicians through complex procedures.

Integration across departments eliminates data silos and redundant data entry.

Quality systems integrate maintenance with procurement, finance, operations, safety, human resources and engineering, ensuring decisions consider impacts across all affected functions.

Reliability engineering support enables proactive maintenance strategies.

Quality systems provide failure mode and effect analysis tools, criticality assessment, reliability centred maintenance frameworks, root cause analysis tools and condition monitoring integration.

Compliance tracking creates systematic processes for meeting regulatory requirements.

Quality systems track statutory inspection due dates with automated alerts, maintain competent person certifications, record mandatory test results, generate regulatory reports and manage compliance documentation.

Auditability ensures operations can demonstrate what occurred, when, why and who performed activities.

Quality systems provide complete audit trails, timestamped records, digital signatures, photograph attachments documenting equipment condition and instant report generation.

Scalability allows systems to grow with operations without requiring replacement.

Quality systems support additional users without performance degradation, accommodate expanding equipment populations, handle increasing transaction volumes and enable multi-site deployments.

Usability determines whether systems are actually used effectively.

Quality systems provide intuitive interfaces requiring minimal training, mobile access enabling field data entry, offline capability for remote locations, rapid response times and configurable dashboards showing relevant information for different roles.

3.3 CMMS vs EAM vs ERP in Mining.

CMMS platforms focus specifically on maintenance management activities. Their scope includes work order management, preventive maintenance programs, parts inventory tracking, labour and contractor scheduling and maintenance performance reporting.

CMMS strengths lie in maintenance-specific functionality depth, relatively simple implementation, lower cost and focused user interfaces.

Limitations include limited integration with other business systems, narrow focus without broader asset lifecycle perspective and minimal reliability engineering capabilities.

EAM systems expand scope to comprehensive asset lifecycle management.

Capabilities include everything in CMMS platforms plus reliability-centred maintenance tools, capital project management, asset performance management, comprehensive asset information management, sophisticated analytics including lifecycle costing and condition monitoring integration.

EAM strengths include integrated asset lifecycle perspective, advanced reliability engineering tools and multi-site capability. Limitations include higher implementation complexity and greater cost.

ERP systems position maintenance as one module within enterprise-wide business management.

Capabilities include all asset management functionality plus comprehensive financial management, supply chain management, human capital management, production planning and business intelligence across all functions.

ERP strengths lie in complete business integration eliminating data silos, single platform reducing IT complexity and enterprise-wide visibility.

Limitations include massive implementation complexity and cost, long implementation timelines and potential over-functionality for smaller operations.

For mining operations, platform selection depends on multiple factors. Small single-site operations may find CMMS platforms sufficient.

Medium operations expanding beyond single sites may benefit from EAM systems. Large multinational mining companies typically implement ERP systems achieving enterprise-wide integration despite implementation challenges.

3.4 How These Systems Support Mining Operations.

Asset management systems contribute across multiple dimensions of mining operations.

Planning and scheduling converts maintenance requirements into resourced, sequenced work programs.

Systems generate preventive maintenance work orders automatically based on configured intervals, enable planners to review backlog and assess priorities, estimate labour and parts requirements, coordinate with operations for equipment availability and create weekly schedules balancing workload across crews.

Work execution provides crews with clear instructions and documentation tools.

Systems deliver work orders to mobile devices showing task descriptions, safety requirements, equipment history and parts lists.

Technicians record time spent, parts consumed, measurements taken, defects found and work completed. They attach photographs and capture digital signatures.

Materials management integrates parts inventory with maintenance workflows.

Systems automatically allocate parts when work orders are created, generate purchase requisitions when stock reaches reorder points, track parts from procurement through consumption, enable kitting functionality and provide parts usage analysis.

Contractor management creates systematic processes for external service providers. Systems maintain contractor databases including capabilities and certifications, enable creation of contractor work orders, track contractor time and costs, verify contractor personnel competencies and manage safety inductions and permit requirements.

Training and competency links personnel qualifications with work requirements. Systems maintain competency matrices showing required qualifications, track individual training completion and currency, prevent assignment of work orders to unqualified personnel, generate training needs analysis and provide training records for compliance demonstration.

Statutory inspections require systematic tracking given regulatory consequences of missed inspections.

Systems maintain registers of equipment requiring statutory inspection with frequencies, generate inspection work orders automatically, track competent person qualifications, record inspection findings and produce statutory inspection registers for regulatory reporting.

Asset lifecycle management supports decisions from equipment acquisition through disposal.

Systems track capital projects, record equipment specifications and installation dates, accumulate maintenance costs throughout operational life, calculate reliability metrics and support replacement analysis.

3.5 The Human Element.

Asset management software delivers value only when people use it effectively, requiring attention to training, adoption, governance and data stewardship.

Training must extend beyond basic system operation to encompass underlying asset management principles.

Users need to understand why data integrity matters, not just which fields are mandatory. Training should be role-specific, ongoing and reinforced through refresher sessions.

Adoption requires demonstrating value to users whose workload initially increases from documentation requirements.

Operations must communicate clearly why implementation is occurring, what benefits will result and what support is available.

Quick wins showing tangible benefits build confidence.

Governance establishes structures and processes ensuring systems continue serving intended purposes. It includes data standards, change management processes, user access controls, performance monitoring and continuous improvement processes.

Data stewardship assigns responsibility for data quality and completeness.

People in these roles monitor their domains for errors and gaps, investigate anomalies, propose improvements and educate users on data entry standards.

Resistance often stems from legitimate concerns that implementations fail to address. Addressing resistance requires understanding underlying concerns and responding through system configuration, training, process adjustment, or infrastructure improvement.

The human element ultimately determines success or failure regardless of technical capabilities.

Successful implementations invest in people as heavily as technology, recognising that technology alone changes nothing, people using technology effectively creates improvement.

4.0 How Asset Management Software Ensures Compliance.

4.1 Turning Guidelines Into Workflows.

Asset management systems translate regulatory guidelines from reference documents into operational workflows that ensure compliance occurs systematically.

Mandatory fields enforce minimum documentation requirements that guidelines specify. If regulations require recording inspector qualifications for statutory inspections, the system makes the qualification field mandatory, preventing work order closure without this information.

Checklists embed guideline requirements into work execution.

A mobile equipment pre-operational inspection checklist might include specific items that regulatory guidelines identify: brake function, steering response, warning devices, lighting, fluid levels, structural condition and guarding integrity. Digital checklists can include photographs, measurements and branching logic requiring additional actions when defects are identified.

Templates create repeatable approaches to common activities. A statutory boiler inspection template might include placeholders for certificate verification, pressure testing procedures, safety device testing, structural examination and documentation requirements.

Templates can be refined based on lessons learned and updated when guidelines change.

Automated scheduling ensures required inspections occur before expiration.

The system calculates due dates based on last inspection date and regulatory frequency, generates work orders automatically in advance and escalates overdue items to supervision when tasks are not completed timely.

Alerts and escalations provide visibility when compliance risks emerge.

The system can alert when competent person certifications approach expiry, when defects identified in inspections are not addressed within required timeframes, or when equipment operates beyond inspection due dates.

Workflow routing enforces approval requirements that guidelines and internal procedures specify. High-risk work orders might require engineer review before execution. Modifications might require design verification and management approval.

4.2 Creating an Audit-Ready Operation.

Regulatory audits examine whether mining operations meet legislative obligations and follow applicable guidelines. Asset management systems position operations to respond effectively by maintaining comprehensive, accessible evidence.

Audit trails document who performed activities, when and what was found.

Every maintenance transaction generates timestamped records showing user identity, work order details, findings and actions taken.

Modifications to records are tracked showing original values, changed values and who made changes.

Regulatory registers compile required information in formats regulators expect.

Statutory inspection registers list equipment requiring periodic inspection, inspection due dates, last inspection dates, inspector qualifications and findings.

Systems generate these registers instantly from underlying transaction data.

Defect management tracks identified defects through resolution.

When inspections identify defects, the system records defect descriptions, risk classifications, required actions, target completion dates and responsible parties. It tracks repair progress and prevents equipment return to service with outstanding critical defects.

Competency verification provides evidence that personnel performing safety-critical work held required qualifications.

The system links completed work orders to personnel who performed them and their competency records showing qualification types, currency dates and training completion.

Document management retains procedures, specifications, drawings, certifications and inspection reports supporting compliance demonstration.

Modern systems provide document repositories linked to equipment and activities.

Historical analysis demonstrates compliance over time rather than just current status. Systems can report inspection completion rates by equipment type and time period, trend defect identification and closure rates and compare performance across sites.

4.3 Reducing Human Error.

Human error contributes to many maintenance-related incidents. Systems help prevent or mitigate these errors.

Procedural compliance improves when systems guide execution.

Checklists ensure technicians address all required steps. Lockout/tagout procedures embedded in work orders ensure isolation verification occurs before maintenance begins.

Guided workflows reduce the likelihood of skipping steps or performing steps out of sequence.

Parts errors decrease when systems verify compatibility before issue.

The system can prevent issuing incorrect parts by validating part numbers against equipment specifications and alert when critical safety items are substituted with alternatives.

Measurement errors become more detectable when systems require entry within expected ranges.

If brake deceleration measurements typically fall between defined limits, the system can flag values outside these ranges for verification.

Schedule errors reduce when systems manage complexity.

Manual scheduling of thousands of maintenance tasks across hundreds of pieces of equipment invites errors including double-booking resources and overlooking equipment unavailability.

Automated scheduling reduces these errors.

Communication errors decrease when systems provide single sources of truth. When multiple people access the same work order, updates are visible immediately to all parties.

Shared information reduces miscommunication risks.

Training currency errors decrease when systems track qualifications and prevent expired credentials. If a technician’s competency expires, the system can prevent assignment of work orders requiring that competency.

4.4 Integrating Safety and Maintenance.

Safety and maintenance are inseparable in mining operations. Asset management systems increasingly integrate these functions.

Critical controls require verification before equipment operation.

Critical controls are barriers preventing hazardous events such as brake systems preventing runaway vehicles and guarding preventing contact with moving parts.

Systems can enforce pre-operational checks verifying critical control functionality before equipment is released for use.

Isolation management ensures hazardous energy sources are controlled before maintenance begins.

Systems can generate isolation certificates identifying all energy sources, track lockout application and removal, require verification testing and prevent work commencement until isolation is confirmed complete.

Permit to work systems integrate with maintenance work orders for high-risk activities. Systems can enforce permit requirements for activities including confined space entry, hot work, electrical work and working at heights.

They verify permit prerequisites are met, track permit validity periods and ensure permit closure before area handback.

Incident investigation links connect equipment failures with safety incidents.

When equipment fails causing or contributing to incidents, the system can link incident records with equipment maintenance histories, enabling investigation of whether maintenance deficiencies contributed and preventing recurrence through corrective maintenance.

Safety observation integration allows reporting of equipment defects through safety systems.

Workers identifying equipment hazards during safety observations or inspections can generate work orders directly from safety reporting systems, ensuring identified defects receive timely attention.

4.5 Practical Scenarios.

Realistic scenarios illustrate how systems operationalise compliance:

Haul truck statutory inspection: The system generates a work order 30 days before the inspection due date. The planner assigns it to a qualified competent person whose certification is verified automatically.

The inspector completes a digital checklist covering brakes, steering, structure and safety systems. Defects are automatically escalated based on severity. The truck cannot return to service until critical defects are addressed. All records are timestamped and auditable.

Crusher shutdown: The shutdown work order triggers generation of isolation certificates for electrical, mechanical and hydraulic systems.

Each isolation point requires verification testing. Parts are kitted in advance based on the maintenance plan.

Contractor work orders include competency verification. Photographs document pre and post-shutdown conditions. Return to service requires signoff from multiple disciplines.

Pressure vessel certification: The system alerts 90 days before certification expiry. A competent inspector is scheduled.

The inspection checklist includes pressure testing, safety valve testing and structural examination. Results are recorded digitally.

Certification documents are attached to the asset record. The next inspection date is automatically calculated and scheduled.

Conveyor guarding audit: An audit work order is created. The inspector photographs all guard conditions.

Non-compliant guards generate defect work orders automatically assigned to maintenance crews.

Progress is tracked through planning, parts ordering, installation and verification. The audit report shows completion status and outstanding items.

5.0 High-Risk Mining Environments and the Need for Quality.

5.1 Why High-Risk Mines Benefit Most.

Certain mining operations present substantially elevated risks due to process complexity, hazardous materials, or operating conditions. These environments benefit disproportionately from quality management systems.

Refineries and smelters process materials at extreme temperatures and pressures using complex chemical reactions.

Equipment failures can release toxic gases, molten metals, or corrosive substances. Process upsets can trigger cascading failures across interconnected systems.

Quality systems provide the systematic verification, inspection tracking and documentation needed to maintain process safety barriers.

Underground mines operate in environments where ground instability, ventilation failures and limited escape routes amplify consequences of equipment failures.

Mobile equipment operating in confined spaces with limited visibility creates collision risks. Electrical systems in potentially explosive atmospheres require rigorous management.

Quality systems ensure critical equipment receives required inspections and maintenance on schedule.

Oil sands operations combine mining with petroleum processing, creating unique hazard combinations. Large mobile equipment operates alongside pressure vessels, electrical infrastructure and hydrocarbon processing facilities.

Extreme cold temperatures stress equipment and complicate maintenance. Quality systems integrate diverse equipment types and maintenance requirements into unified management frameworks.

Remote operations face challenges from isolation, extreme weather and limited emergency response infrastructure.

Equipment failures that would be minor inconveniences at operations near urban centres can become life-threatening emergencies in remote locations.

Quality systems provide the systematic approach needed when informal coordination is insufficient.

5.2 The Cost of Failure.

Equipment failures in high-risk mining environments generate consequences far exceeding repair costs.

Safety consequences can include fatalities, serious injuries and long-term health impacts. A brake failure on a loaded haul truck descending a steep ramp can result in multiple fatalities.

A pressure vessel rupture can kill nearby workers instantly. A ventilation fan failure underground can create toxic atmospheres affecting dozens of personnel.

Environmental consequences can persist for decades. A tailings dam failure can release millions of cubic metres of contaminated material into watersheds, destroying ecosystems and contaminating drinking water supplies.

A process equipment failure can release toxic substances requiring extensive remediation.

Production losses from major equipment failures can reach millions of dollars daily. A processing plant shutdown halts revenue generation while fixed costs continue. A mobile equipment fleet shortage constrains production across entire operations.

Legal exposure includes regulatory prosecutions, civil litigation from injured parties, shareholder actions and environmental remediation orders.

Prosecutions can result in multi-million dollar fines and executive imprisonment. Civil litigation can continue for years.

Reputational damage affects relationships with communities, regulators, investors and employees.

Major incidents receive international media coverage. Communities may oppose expansion projects. Investors may divest holdings. Employees may seek employment elsewhere.

5.3 How Quality Systems Reduce These Risks.

Quality systems reduce risks through multiple mechanisms working in combination.

Systematic verification ensures critical equipment receives required inspections on schedule by qualified personnel.

Rather than relying on individual memory or initiative, systems generate inspection work orders automatically, verify inspector qualifications, enforce completion of required tests and escalate overdue items.

Evidence-based decision making replaces intuition with data. Systems provide equipment histories showing failure patterns, maintenance cost trends and reliability metrics.

Decisions about equipment replacement, inspection intervals and maintenance strategies are informed by comprehensive information rather than assumptions.

Consistency across shifts and crews ensures all personnel follow the same standards. Work order templates, digital checklists and approval workflows standardise execution regardless of who performs work.

This consistency prevents the degradation that occurs when standards vary by shift or individual.

Early defect detection prevents minor issues from progressing to critical failures. Systematic inspections identify deterioration early.

Condition monitoring integration provides advance warning of developing problems. Corrective action occurs before failures happen rather than after.

Compliance assurance reduces regulatory risk. Systems maintain current statutory inspection records, track competent person certifications, document required testing and generate audit evidence.

Operations can demonstrate due diligence to regulators, reducing prosecution risk and severity of penalties when incidents occur.

Knowledge retention prevents loss of critical information when experienced personnel leave.

Equipment histories, inspection findings, maintenance procedures and lessons learned are captured in systems rather than existing only in individual memory. New personnel access this knowledge to avoid repeating past mistakes.

Continuous improvement becomes systematic rather than sporadic. Performance metrics track trends over time. Root cause analysis identifies recurring issues.

Management review processes examine effectiveness and implement improvements. Quality systems provide the foundation for disciplined improvement.

6.0 The AI Acceleration.

6.1 AI Is Now Improving AI.

Artificial intelligence development has reached a point where AI systems themselves are accelerating AI advancement.

This creates a feedback loop fundamentally different from previous technological evolution.

Machine learning models train on datasets that include outputs from previous AI systems. Natural language models generate training data for subsequent model generations.

AI assists in designing more efficient neural network architectures. AI optimises hyperparameters for AI training processes.

This self-reinforcing cycle creates exponential rather than linear improvement rates. Capabilities that required years to develop now emerge in months.

Technologies considered impossible become operational rapidly. Predicting future capabilities becomes increasingly difficult as improvement accelerates.

For mining asset management, this acceleration means software capabilities will advance faster than organisations can fully implement current functionality.

The question shifts from “what can these systems do” to “how rapidly can we adapt to expanding capabilities.”

6.2 What AI Can Already Do in Mining Asset Management.

AI capabilities operational in mining today include:

Predictive maintenance analyses equipment sensor data, maintenance histories and operating conditions to forecast failures weeks or months in advance. Vibration analysis detects bearing degradation.

Oil analysis identifies contamination patterns. Thermal imaging reveals electrical hot spots. These predictions enable planned interventions preventing unplanned failures.

Data cleansing automatically identifies and corrects errors in maintenance databases. AI detects duplicate records, inconsistent formatting, invalid values and missing information.

It proposes corrections based on patterns in surrounding data. This cleansing improves data quality without manual review of millions of records.

Compliance monitoring continuously compares equipment records against regulatory requirements.

AI identifies approaching inspection due dates, expired certifications, overdue defects and gaps in documentation. It generates alerts and recommendations for corrective action.

Automated documentation extracts information from unstructured sources including handwritten notes, photographs and legacy systems.

Natural language processing converts free text into structured data. Computer vision reads gauges and instrument panels in photographs.

Historical information becomes accessible and analysable.

Risk detection identifies patterns indicating elevated failure risk.

AI recognises combinations of factors that individually appear normal but collectively signal problems. It flags equipment requiring attention that traditional threshold-based monitoring would miss.

6.3 Why Predicting the Future Is Impossible.

To accurately predict the future capabilities of CMMS, EAM and ERP systems in mining, a person would need to know more than the most advanced AI models currently know, which is impossible by definition.

AI development has surpassed human ability to fully understand system capabilities. Neural networks contain billions of parameters operating in ways that even their developers cannot completely explain.

Emergent capabilities appear unpredictably as models grow larger and training data expands.

This creates fundamental uncertainty about future directions. Technologies that seem impossible today may become routine tomorrow.

Capabilities that appear essential may become obsolete rapidly. Investment decisions must acknowledge this uncertainty rather than assuming linear extrapolation from current trends.

The only certainty is continued rapid change. Systems will become more capable. AI will integrate more deeply into asset management workflows.

The boundary between human decision making and automated decision making will shift continuously. Organisations must prepare for this uncertainty.

6.4 What Mining Companies Can Do.

Given this unpredictable future, mining companies should focus on foundational capabilities that remain valuable regardless of specific technological directions:

Invest in quality systems that provide solid foundations for enhancement.

Well-designed databases, standardised workflows, comprehensive data capture and robust integration create platforms for adding advanced capabilities as they emerge. Poor quality systems constrain AI effectiveness regardless of algorithm sophistication.

AI capabilities are only as strong as the data they rely on.

Organisations need clear data standards, robust validation rules, and active stewardship to maintain integrity.

Historical data should be cleansed to maximise its usefulness, and governance frameworks must prevent quality from degrading over time.

When data is reliable, AI delivers meaningful insights; when it isn’t, even the most advanced models produce nothing more than sophisticated nonsense.

Build governance frameworks that enable controlled evolution. Establish change management processes, testing protocols, training programs and performance monitoring. Governance allows adopting new capabilities systematically rather than chaotically. It prevents technology changes from disrupting operations.

Invest in training that develops understanding of underlying principles rather than just current system operation.

Train personnel in asset management fundamentals, reliability engineering concepts, data analysis methods and continuous improvement approaches. This knowledge remains valuable as specific systems change.

Foster a culture that embraces systematic improvement. Encourage questioning current practices, experimenting with new approaches, learning from failures and sharing knowledge.

Cultural capabilities adapt to technological change more readily than rigid processes designed for specific systems.

Maintain flexibility in technology strategies. Avoid commitments to specific platforms or vendors that prevent adopting superior alternatives as they emerge.

Use standards-based interfaces enabling system replacement or integration. Design architectures that accommodate evolution.

Focus on outcomes rather than specific technologies. Define what operations need to achieve, safety, compliance, reliability, efficiency, and evaluate technologies based on their contribution to these outcomes.

Avoid pursuing technology for its own sake.

The rapid pace of AI advancement makes long-term technology predictions unreliable. Mining companies succeed by building strong foundations, maintaining flexibility and focusing on fundamental capabilities that support adaptation regardless of specific technological directions.

7.0 Conclusion.

Government guidelines and quality asset management software represent complementary pillars of effective mining operations in an increasingly complex regulatory and technological environment.

Guidelines define what must be done by translating complex legislation into practical, accessible requirements.

They specify inspection frequencies, competency requirements, testing procedures and documentation standards that operations must meet.

They provide consistency across jurisdictions, operations and equipment types and incorporate lessons learned from decades of incidents and industry experience.

Quality software systems operationalise these requirements by converting guidelines into workflows, automating scheduling, enforcing data standards, tracking competencies, managing defects and generating audit evidence.

They reduce human error through systematic processes, improve consistency across shifts and crews, enable evidence-based decisions through comprehensive data and support continuous improvement through performance monitoring.

The integration of guidelines and systems creates management capabilities exceeding either element alone.

Guidelines without systems remain paper documents requiring manual implementation prone to inconsistency and oversight.

Systems without guidelines lack the regulatory foundation ensuring compliance with legal obligations. Together, they create structured, auditable, effective approaches to managing mining’s complex hazards.

Artificial intelligence now accelerates this integration by adding predictive capabilities, automated monitoring and intelligent decision support.

AI analyses patterns humans cannot detect, processes volumes of information impossible to review manually and operates continuously without fatigue or distraction. This acceleration creates both opportunities and challenges for mining operations.

The opportunities include preventing failures before they occur, optimising maintenance timing and methods, improving resource utilisation and enhancing safety through better risk detection.

The challenges include rapidly changing capabilities, uncertain future directions and the need for continuous adaptation.

Mining companies that invest in quality systems today, with robust data integrity, standardised workflows, comprehensive integration and strong governance, position themselves to exploit AI capabilities as they emerge.

Those that treat compliance as a paper exercise, view software as merely administrative burden, or neglect data quality will find themselves increasingly disadvantaged.

The convergence of regulatory requirements, quality management systems and artificial intelligence represents more than technological evolution.

It constitutes transformation in how mining operations manage assets, ensure safety, demonstrate compliance and achieve reliability.

Operations that embrace this transformation systematically will thrive.

Those that resist or approach it haphazardly might struggle.

The importance of government guidelines and quality software in mining ultimately reflects the industry’s fundamental reality: mining involves significant hazards requiring disciplined management, complex equipment requiring systematic maintenance and regulatory obligations requiring comprehensive demonstration.

Guidelines provide the framework. Quality systems provide the implementation.

Together, they enable mining operations that protect workers, preserve the environment, meet legal obligations and deliver operational excellence.

8.0 Bibliography.

1. Mine Health and Safety Management – Michael Karmis (ed.)

2. SME Mining Engineering Handbook – Peter Darling (ed.)

3. Risk Management in the Mining Industry – Dmitriy Nurković et al.

4. Maintenance and Reliability Best Practices – Ramesh Gulati

5. Asset Management Excellence: Optimizing Equipment Life-Cycle Decisions – John D. Campbell, Andrew K.S. Jardine, Joel McGlynn

6. Handbook of Maintenance Management and Engineering – Mohamed Ben-Daya et al. (eds.)

7. Reliability-Centered Maintenance – John Moubray

8. Safety and Health in Mines: Handbook of Occupational Safety and Health – Edited volume including mining safety chapters

9. Occupational Health and Safety in Mining – K. Verma et al.

10. Mining Environment: Problems and Remedial Measures – K. Pathak

11. Engineering Asset Management – Systems, Professional Practices and Certification – Joe Amadi-Echendu et al. (eds.)

12. Intelligent Predictive Maintenance: Data Analytics and AI for Asset Management – Sanjay Sharma et al.

13. Machine Learning for Asset Management – Emmanuel Jurczenko (ed.)researchers.mq

14. Safety Management Systems in Mines – Daniel Ashby

15. Underground Mining Methods: Engineering Fundamentals and International Case Studies – William A. Hustrulid, Ricardo C. Bullock (eds.)

16. International Council on Mining and Metals: Health and safety – International Council on Mining and Metals

17. ICMM Performance Expectations – International Council on Mining and Metals

18. Global Mining Guidelines Group – Our Work – Global Mining Guidelines Group

19. ISO 55000 series – Asset management – International Organization for Standardization

20. Mining: Guidance and resources – UK Health and Safety Executive

21. Mine Safety and Health at a Glance – U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration

22. Mine Safety and Health Program – NIOSH Mining Program

23. Mine Safety and Inspection Act and Regulations – Guidance – Government of Western Australia, DMIRS

24. Queensland Mining and Quarrying Safety and Health – Guidance Notes and Recognised Standards – Resources Safety & Health Queensland

25. Risk Management Handbook for the Mining Industry – NSW Resources Regulator

26. Asset management in mining: A review of maintenance strategies – Journal article via ScienceDirect

27. Digital transformation and the rise of predictive maintenance in mining – McKinsey & Company

28. Artificial Intelligence and the Mining Industry – World Economic Forum

29. Implementing an Asset Management System in the Mining Industry – Assetivity

30. Predictive Maintenance in Mining: Leveraging AI and IoT – IBM